© Variety Film / Variety Distribution

Richard Johnson, who died in 2015 at the age of 87, was a busy and much-admired theatrical actor whose stage CV included Pericles Prince of Tyre, Romeo and Juliet, As You Like It, Julius Caesar, Cymbeline, Twelfth Night and Antony and Cleopatra and who could boast that he’d worked with stage directors as distinguished as Tony Richardson and Peter Hall.

From the 1970s on, he was also a popular guest star on TV shows on both sides of the Atlantic, so that, for instance, he appeared in Hart to Hart (1979), Magnum P.I. (1981 & 83) and Murder, She Wrote (1987) in the USA and in Tales of the Unexpected (1980, 81 & 82), Dempsey and Makepeace (1986) and the inevitable Midsomer Murders (1999 & 2007) in the UK. Indeed, it was on television that I first saw Johnson, guest-starring in a 1975 episode of Gerry Anderson’s silly but stylish science-fiction show Space: 1999. He played the astronaut husband of series regular Dr Helena Russell (Barbara Bain), who’s been transformed into anti-matter. Even back then, at 10 years old, I found Bain’s character so dull and humourless that this didn’t surprise me. Being married to her would transform anyone into anti-matter.

However, it’s for his film work that I’ll remember him – never more so than for his performance as the main male character, Dr John Markway, in Robert Wise’s spooky-house classic The Haunting (1963). I think The Haunting is one of the scariest films ever made. In fact, both Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese are on record as saying that it’s the scariest film ever made. The fact that The Haunting is based on a terrific novel, 1959’s The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson, doesn’t do it any harm, either.

The initially smooth and charming Dr Markway investigates strange phenomena in an old, rambling and supposedly haunted house with a group of helpers – the young man who’s inheriting the place (Russ Tamblyn), a psychic (Claire Bloom) and a lonely oddball called Eleanor Vance (Julie Harris), in whom the house’s supernatural forces start taking an interest. Markway’s wife – Lois Maxwell, who was Miss Moneypenny in the first 14 James Bond movies – also turns up at the premises when things are getting properly scary, which the now-unnerved doctor isn’t happy about.

© Argyle Enterprises / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Director Robert Wise understood that the most frightening things are things we don’t see and are left to our imaginations; because what we are capable of imagining in our mind’s-eye is far worse than anything a special-effects or make-up artist can conjure up onscreen. So, in The Haunting, we hear rather than see. The film’s characters find themselves reacting to all manner of weird and disturbing noises made by mysterious somethings off screen. Wise’s sound editors played these noises aloud while Johnson and his co-stars were filming their scenes, which added to the rattled authenticity of their performances.

In addition, Johnson’s Markway gets to utter the iconic line: “Look, I know the supernatural is something that isn’t supposed to happen, but it does happen.” These words impressed Rob Zombie so much that he and his band White Zombie sampled them on the 1995 song Super–Charger Heaven. (The song also features Christopher Lee from 1976’s To the Devil a Daughter snarling, “It is not heresy and I will not recant!”)

Needless to say, when Hollywood got around to remaking The Haunting in 1999 with action-movie director Jan de Bont at the helm, the result was dire. It abandoned Robert Wise’s ultra-creepy, suggest-don’t-show approach and relied instead on a crass welter of computer-generated special effects. I hate it even more than I hate the 2006 remake of The Wicker Man with Nicholas Cage.

Elsewhere, Richard Johnson’s film biography contains an interesting what-if. In the early 1960s, when Sean Connery was known only as a bit-part actor, former body builder and former Edinburgh milkman, Johnson turned down the opportunity to play James Bond. Terence Young, who was lined up to direct the first Bond movie, 1962’s Dr No, approached him, but Johnson didn’t like the idea of being stuck playing the same character in a long contract.

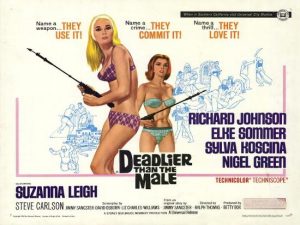

However, later, Johnson played Bulldog Drummond, a British literary action-hero who’d inspired Ian Fleming when he started writing the Bond novels in the early 1950s. He was Drummond in two movies, Deadlier than the Male (1967) and Some Girls Do (1969), both directed by Ralph Thomas. Ironically, the films are far more influenced by James Bond’s cinematic franchise, massively popular by then, than they are by the original Bulldog Drummond books, which were written from 1920 to 1937 by H.C. McNeile (‘Sapper’) and from 1938 to 1954 by Gerald Fairlie. The books portrayed Drummond as an English gent with combat experience from World War I and, frankly, some very racist views of foreigners, having adventures in an upper-crust world of country houses, servants and vintage motorcars.

© Greater Films Ltd / Rank Film Distributors

I’ve seen Deadlier than the Male and, because I read a few Bulldog Drummond books in my boyhood, I find it fascinatingly peculiar if nothing else. It transfers Drummond to a glamorous Swinging Sixties setting populated with luxurious islands, private jets, yachts, speedboats, brassy music, bikinis, dolly-birds and gadgets (like giant, computer-controlled chessmen). At least, that’s ‘glamorous’ as far as its less-than-Bond-sized budget allows. Its chief gimmick is Elke Sommer and Sylvia Koscina as a pair of voluptuous, presumably sapphic assassins who go about their deadly work with a kooky cheerfulness. “Goodbye, Mr Bridgenorth!” they cry as they tip a victim (played by future 1970s British sitcom-star Leonard Rossiter) off a high building. Mr Kidd and Mr Wint did this schtick more amusingly in 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever. Johnson is serviceable as Drummond, but seems bemused by the proceedings. It’s not among his most memorable performances.

Incidentally, in 1951, Johnson’s second-ever film appearance had been an uncredited one as a ‘Control Tower Operator’ in an old-school Bulldog Drummond movie. This was Calling Bulldog Drummond, featuring Walter Pidgeon in the title role.

Johnson’s other 1960s movies include Michael Anderson’s Operation Crossbow (1964), a surprisingly downbeat World War II action-adventure movie in which he plays the British minister who sends George Peppard, Tom Courteney and Jeremy Kemp on a suicide mission to sabotage the Nazis’ V1 / V2 rocket project; and Basil Dearden’s epic costume-drama Khartoum (1966), where he’s an aide to Charlton Heston’s General Charles Gordon, locked in conflict with Laurence Olivier’s Muhammad Ahmed in 1880s Sudan.

For me, his most interesting 1960s role (apart from The Haunting) is 1966’s La Strega in Amore, or The Witch in Love, a black-and-white Italian movie in which he plays a young man hired by a wealthy, elderly woman (Sarah Ferrati) to catalogue her huge library. The manner of Johnson’s recruitment is sinister. First the woman stalks him, then she places in a newspaper a job advertisement that’s so oddly detailed he’s the only person in Rome who can meet its specifications. Despite his misgivings, Johnson decides to stay in the woman’s luxurious palazzo when he meets her beautiful and alluring daughter (Rosanna Schiffiano). But the longer he remains with the two women, the more his grip on reality loosens and the stronger the insinuation becomes that mother and daughter are the same person – two versions of la strega, the witch of the title.

© Arco Films / Cidif

Italian cinema was awash at the time with full-blooded, gothic horror movies, but director Damiano Damiani ploughs his own furrow with La Strega in Amore, making it dreamy rather than macabre and creating something that wouldn’t seem out-of-place in an arthouse cinema. Unfortunately, the film’s premise doesn’t justify its one-hour-49-minute running time and it could have been a half-hour shorter. Still, after seeing Johnson play fairly upright and decent characters, it’s interesting to see him in this playing a vain bastard, somebody you partly feel is getting what he deserves. And after the languid, arty build-up, the film’s nasty climax delivers a jolt.

In 1975, Johnson not only starred in, but also wrote the original story for the forgotten thriller Hennessy, directed by Don Sharpe. This is perhaps the first film inspired by Northern Ireland’s Troubles, which’d erupted in 1969. It’s about an IRA explosives expert (Rod Steiger) who, after the British Army kills his wife and child, decides to blow up the state opening of the British parliament, destroying both the government and the Queen. Johnson gives an endearing performance as the weary, dishevelled policeman trying to stop him.

Hennessy is patchy but has an impressive cast that also includes Lee Remick, Trevor Howard, Eric Porter, a young Patrick Stewart and an even-younger Patsy Kensit (playing Steiger’s doomed daughter). The final scenes in the House of Commons, featuring the Queen, landed the filmmakers in trouble because they used real footage that Buckingham Palace had authorised without knowing it would end up in a film. Also, at the time, the film’s subject-matter was extremely sensitive. As a result, its British cinematic release was almost non-existent.

© Hennessy Film Productions / American International Pictures

Presumably because The Haunting had put him on the radar of horror filmmakers, Johnson continued to appear in scary movies during the 1970s and 1980s. These included Ovidio G. Assonitis and Roberto Piazzoli’s Beyond the Door (1974), Massimo Dallimano’s The Cursed Medallion (1975), Pete Walker’s The Comeback (1978), Sergio Martino’s Island of the Fishermen and The Great Alligator River (both 1979), and Don Sharpe’s What Waits Below (1984). He was also in Roy Ward Baker’s kiddie-orientated The Monster Club (1981). This was the ninth and final horror-anthology movie made by American (but British-based) producer Milton Subotsky. By my calculations, Subotsky’s nine anthologies contain a total of 37 stories. The Vampires, the one featuring Johnson in The Monster Club, is possibly the worst of all 37. You feel like banging your head against the nearest hard surface at the story’s punchline, when the bloodsucking Johnson reveals he’s escaped destruction at the hands of some vampire-hunters thanks to a ‘stake-proof vest’.

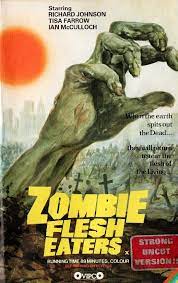

In 1979, 16 years after The Haunting, Johnson played another doctor, a medical one, in a very different sort of horror movie. This was the Italian film Zombie Flesh Eaters, directed by the legendary Lucio Fulci. He was Dr Menard, the weary, dishevelled – by this time Johnson was good at doing ‘weary and dishevelled’ – but stoical GP on a remote Caribbean island trying to deal with an epidemic of reanimated, hungry cadavers. The movie is both gleefully gory and lovably schlocky, with its highlights including a once-seen-never-forgotten underwater battle between a shark and a zombie. Despite this, Johnson gives it his all. He spouts the less-than-epic dialogue with as much earnestness as he would doing Shakespeare.

Financial pressures meant Johnson wasn’t able to retire and he continued working until his death. According to his Wikipedia entry, he said in a 2000 interview he was “constantly worried where the next job was coming from,” but then quipped: “At least at my age the opposition gets less and less because they keep dying.” His 21st century roles included ones in Simon West’s Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), Woody Allen’s Scoop (2006), Mark Herman’s The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (2008) and Tom Browne’s acclaimed Radiator (2014).

Also in his later years, after Lucio Fulci had become a cult figure and Zombie Flesh Eaters had become something of a camp classic, Johnson was invited to horror movie conventions to discuss his experiences making the film. A serious Shakespearean actor he may have been, but he always sounded gracious and affectionate towards Fulci. He was even complimentary about the film’s most notorious moment, wherein his character’s wife gets grabbed by the hair and dragged through a freshly-smashed hole in a door by a rotting zombie arm. In the process, in loving close-up, she gets a big splint of wood protruding from the hole embedded in her eye – this was surely what cemented Zombie Flesh Eaters’ place on Britain’s list of banned ‘video nasties’ in the 1980s. According to the journalist Tristan Bishop, an 80-something Johnson enthused to him at one convention, “That spike in the eyeball scene! Wasn’t that genius? So cinematic!”

Clearly, Richard Johnson was a man who enjoyed his work.

© Argyle Enterprises / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

© Variety Film / Variety Distribution