From facebook.com / Peebles Beltane Festival

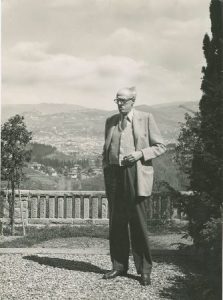

At the end of last month I received some sad news. Ian Jenkins, a teacher, a politician and a well-kent face in the Scottish town of Peebles, where I spent some of my formative years, had passed away at the age of 84.

He taught me English for four of the five years, from 1977 to 1982, that I attended Peebles High School. It’s impossible to think of the English-literature texts I had to study during those four years – novels like Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd (1871) and Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song (1932) and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954); drama like Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949) and The Crucible (1953), Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953), Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party (1959), Willis Hall’s The Long and the Short and the Tall (1959), Barry England’s Conduct Unbecoming (1969) and the Shakespeare plays Romeo and Juliet (1595), Hamlet (1601) and Macbeth (1606); and poems by Robert Burns, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Gerard Manley Hopkins, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, John Betjeman and Ted Hughes – without hearing Ian’s voice, with its gentle, mellifluous accent, explaining and quoting from them.

He hailed from the Isle of Bute in the Firth of Clyde and, to my ears at least, his accent seemed mellifluous. Mind you, I came from western Northern Ireland, where folk often spoke broadly, gruffly and roughly. Compared to there, most types of Scottish accent sounded charming to me.

When I was at school, attitudes about educating young people had shifted from the old-fashioned, dictatorial approach to a more humane one. But even in the late 1970s and early 1980s there remained some intimidating, traditional-minded teachers who made pupils feel as uncomfortable and on-edge in their classrooms as newly-conscripted troops hunkered down in the trenches. Also, the European Court of Human Rights didn’t get around to banning the tawse – that palm-flaying form of corporal punishment informally known as ‘the belt’ – from Scottish schools until the mid-1980s.

But you never approached Ian Jenkins’ classroom with a feeling of trepidation. You never worried he’d got out of the wrong side of bed that morning and he might lose the rag and start swinging the tawse at the slightest provocation. No, you looked forward to his lessons because he was a mellow, kindly and jolly soul.

And unlike some of his colleagues, he treated his pupils like grown-ups. I remember the occasional English lesson with him giving way to a debate about one of the big political issues of the time, such as nuclear disarmament – Soviet tanks had rolled into Afghanistan in December 1979, East-West tensions were high and the prospect of the world vanishing in a puff of mushroom-shaped, radioactive smoke was not a remote one – or whether there should be a Western boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics as a protest against that Soviet invasion.

Another issue of great geopolitical importance we discussed was the terrible performance – under the hapless stewardship of Ally MacLeod – by Scotland’s national football team at the 1978 World Cup in Argentina.

© Revelation Press

I remember one lesson that made me wonder how happy he was being a teacher. In teaching, after all, you tend to talk about the same things year after year, in the same surroundings, with the only element of change being your pupils arriving, growing older, and departing again. During that lesson we looked at Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s 1842 poem Ulysses, in which the legendary Greek hero is now an old man, is back home after his many travels and adventures, and faces spending the remainder of his life in peaceful domesticity. But he decides, “To hell with that!” He resolves to set sail again and look for new adventures: “‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world / Push off and sitting well in order smite / The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds / To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths / Of all the western stars, until I die.”

Wistfully, Ian remarked that sometimes he felt he should follow Ulysses’ example and set off in search of excitement and adventure before it was too late. And by the time of the poem, Ulysses had already done stuff. He’d fought in the Trojan War, escaped from the cyclops Polyphemus, encountered the sorceress Circe, survived the Sirens, sailed between Scylla and Charybdis and been the lover of the nymph Calypso. Whereas Ian had merely taught English at a high school in Peebles. I’m sure, though, countless Peebles schoolkids during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s were glad he didn’t clear off as Ulysses did and persevered with the teaching.

He certainly had my gratitude, for the help he gave me with my writing. I’d been writing stories since I was nine or ten years old and in my teens, after class, I’d sometimes approach Ian clutching the latest piece of fiction I’d penned and ask him if he could read it and offer me advice on it. The poor man. At the time I was heavily influenced by the great, if verbose, American horror writer H.P. Lovecraft and my stories were written in florid prose and featured some hopefully horrific (though more often absurd) subject-matter. For example, one story I gave him was about a man who comes into possession of a grandfather clock that’d once belonged to a witch and discovers that the witch’s monstrous familiar still lives inside it – the inspiration for this effort was Lovecraft’s The Dreams in the Witch House (1933). Yet Ian was remarkably patient, civil and encouraging in his feedback. He did advise me to use fewer adjectives, though.

I left school in 1982 but kept in touch with Ian and his wife Midge – who was also a teacher, of French, and who at school had had the unenviable task of trying to coax the euphonic French language out of my broad, gruff and rough Northern Irish-accented mouth. I frequently bumped into them around Peebles and also sometimes called at their house, which seemed a wonderful place to me because: (1) it was full of books; and (2) it contained whisky too, a generous dram of which was pushed my way any time I visited.

Ian was always eager to lend or recommend books to me. The first time I read Ernest Hemingway, it was a collection of Hemingway’s short stories he’d lent me – no doubt hoping I’d discover from it you could write effective prose without sticking three or four adjectives before every noun. Another book from the Jenkins lending-library important for me was one that introduced me to the ghost stories of M.R. James. In the early 1980s, in response to his urging, I procured and read a copy of Alasdair Gray’s Lanark (1981), now regarded as the most important Scottish novel of the second half of the 20th century. And he championed the works of Thomas Hardy. After reading Hardy’s Jude the Obscure (1895), I remember arguing with him – in a friendly way, over a nip of whisky – about the book’s most outlandish character, Little Father Time. “He’s a bit over the top,” I said. Ian retorted, “Aye, but he’s fun.”

© Penguin Classics

I managed, though, to read Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1993) before he did. In the mid-1990s Ian told me one of his pupils had decided to write her English Sixth-Year-Studies dissertation about it. So, he thought he’d better familiarise himself with Trainspotting to be able to give her support. “Well,” I asked, “what did you think?” He replied, “It’s, er, robust.”

Then in 1999, like Ulysses, Ian did set sail in search of new adventures. Okay, he only sailed 21 miles up the road, from Peebles to Edinburgh, where he became a Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) representing the constituency of Tweeddale, Ettrick and Lauderdale, which included Peebles. But as this was the first time Scotland had had its own parliament for nearly 300 years, it was a historical occasion and being one of the new MSPs was an achievement. I’d known he was a political creature and in our conversations politics was a regular topic. He was a lifelong Liberal Democrat, which led to some bickering between us – again in a friendly way, because it was invariably done over a nip of whisky – because during the 1990s my lapel regularly sported a badge for the Scottish National Party (SNP).

I lived in Edinburgh during the late 1990s. July 1st, 1999, saw the official opening of the Scottish Parliament. As I’ve said, this was the first time since 1707 there’d been a Scottish parliament, so it was a big occasion with a big parade. Because the streets of central Edinburgh are narrow and aren’t conducive to large crowds gathering to watch a parade, a giant screen had been set up in East Princes Street Gardens so that folk could watch the festivities there. That was where I headed. The parade included delegations of schoolchildren from all over Scotland and, at one point, a group of kids from Peebles High School appeared on the screen. Then the camera cut to an excited, jolly-looking man jumping up and down and waving at them. I burst out laughing, which prompted a woman standing nearby to ask, “What’s the matter?” I told her proudly, “That’s my English teacher.”

During his four years as an MSP, Ian served as the Liberal Democrats’ spokesperson for Education, Culture and Sport. It pleased me that Robert McNeil, the journalist and sketch-writer who covered the Scottish parliament for the Scotsman newspaper, referred to him affectionately as ‘Jolly Jenkins’. I worked on the upper part of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile and a couple of times bumped into him there – in those days, the parliament did its business in the Church of Scotland’s General Assembly Hall on the Mound, before the official parliament building was opened at the foot of the Mile in 2004 – and, as ever, he was happy to stop and chat.

After he stood down as an MSP in 2003, I continued to bump into him and Midge in Peebles. I’d encounter them at Peebles’ annual agricultural show. At one show in the early 2010s he told me how pissed-off he was that the Nick Clegg-led Liberal Democrats had formed a coalition government with the Conservatives. I’d also see them at Peebles’ Eastgate Theatre. One evening, my partner and I arrived there for a late showing of the 2014 Mike Leigh movie Mr. Turner, which starred Timothy Spall as the unorthodox English painter J.M.W. Turner, and we met the Jenkinses emerging from an earlier showing of it. “I hear Timothy Spall grunts a lot,” I said. Bemused, they confirmed that, yes, Spall does grunt a lot in the movie. Our last meeting must have been in 2015. That was when I had some work lined up in Kolkata in India and I needed to write the name and contact details of a possible referee on the application form for an Indian visa. So, I asked Ian if he’d be my referee and, naturally, he agreed.

It saddens me that I didn’t see him after that. My work situation changed, which kept me in Asia for most of the time and reduced my opportunities to go back to Scotland. Covid-19 happened, which changed my work situation even more and reduced the opportunities to go home even further. There were many things I’d have liked to tell him during the past ten years. I’d have loved to report that, finally, I’d managed to read all the novels written by his beloved Thomas Hardy – even the most obscure ones, like Desperate Remedies (1871), A Laodicean (1881) and Two on a Tower (1882). Not being a fan of Britain’s honours system, I’d have enjoyed ribbing him about the fact that, in 2024, he’d been made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) – though I should add that he got his MBE for very good reasons, for his work for charity and services to his local community. “Does this mean,” I’d have asked, “you can now call yourself ‘Emperor Jenkins’?”

Most of all, I’d have liked to tell him that the number of short stories I’ve had published has now reached treble figures. My 100th story appeared in print in 2024. At least part of that achievement is due to the encouragement I got from my old English teacher.

After he died, one of my siblings sent me a link to a Peebles Facebook page, where the announcement of his passing had brought a flood of condolences and tributes from people who’d known him, often first of all as pupils in his classroom. It felt like half of Peebles had posted. Dozens and dozens of messages spoke of his kindness and decency, his patient and good-humoured teaching, his sense of civic duty, how he did his best to help and encourage the folk he came in contact with, how – whoever you were and whenever and wherever you met him – he was always pleased to stop and blether with you. Which reminded me that my experiences of the man were by no means unique.

So, Ian Jenkins might not have been a hero in the roving, adventuring, Greek-mythological mode of Ulysses. But in terms of the positive impact he had on many people’s lives, and the simple pleasure of his company, he was a hero – a true local hero.

© BBC