© Maverick / Warner Bros.

September 2025 reminds me of the song Ironic by Alanis Morissette. The song’s lyrics contain many examples of things that are ironic, for example, “An old man turned ninety-eight / He won the lottery and died the next day,” or “a free ride when you’ve already paid”, or “ten thousand spoons when all you need is a knife.” Although, as the comedian Ed Byrne has pointed out, some of the situations mentioned in the song aren’t actually ironic. “A traffic jam when you’re already late,” for example. As Byrne observed, that’s really only ironic if you’re a city planner.

Anyway, should Alanis Morissette ever write a sequel to Ironic, the month that has just passed should provide her with more than enough material. To me, it’s the most ironic month I’ve ever experienced. Here are a few reasons why I think so.

[Incidentally, this blog-entry contains references to American right-wing activist Charlie Kirk. Please note that it’s possible to hold two opinions about Kirk at the same time, though many people out there are unable – or unwilling – to accept this.

Firstly, you can be horrified by Kirk’s murder, excoriate the fact that it happened while he was on a university campus exercising his right to free speech, and feel sorry for his young family. Secondly and simultaneously, you can detest many of the things that came out of his mouth. Things about black people. (“Happening all the time in urban America, prowling blacks go around for fun to… target white people, that’s a fact. It’s happening more and more.”) About women. (“Reject feminism. Submit to your husband, Taylor. You’re not in charge… And most importantly, I can’t wait to go to a Taylor Kelce concert… You’ve got to change your name. If not, you don’t really mean it.”) About Islam. (“Islam is the sword the left is using to slit the throat of America.”) About trans-people. (“We need to have a Nuremberg-style trial for every gender-affirming clinic doctor. We need it immediately.”). And so on. Also, you can be dismayed by the fact he made himself very wealthy by saying such things.]

September 10th

Charlie Kirk once said this of American gun ownership and the attendant, heavy toll of American gun-related deaths (16,576 in 2124, excluding suicides). “You will never live in a society when you have an armed citizenry and you won’t have a single gun death. That is nonsense. It’s drivel… I think it’s worth it. I think it’s worth to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment to protect our other God-given rights.”

Today, while speaking at Utah Valley University, Kirk was shot dead by an American citizen, using a gun, which it was his God-given right to own under the Second Amendment. How tragically ironic and tragically American.

September 11th

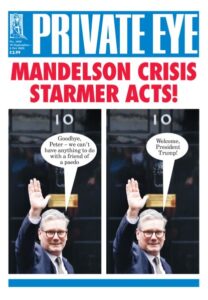

UK prime minister Keir Starmer sacked Peter Mandelson from his job as British ambassador to the USA. This was on account of Mandelson being an old friend of the late millionaire paedophile and human-trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. Mandelson had even waxed lyrically about Epstein in writing: “Once upon a time, an intelligent, sharp-witted man they call ‘mysterious’ parachuted into my life… wherever he is in the world, he remains my best pal!”

Five days later, another old friend of Jeffrey Epstein, who’d also, allegedly, waxed lyrically about him in writing (“We have certain things in common, Jeffrey. Yes, we do, come to think of it. Enigmas never age, have you noticed that…?”), arrived in Britain. This was Donald Trump. Starmer rolled out the red carpet and treated him to a state visit.

September 13th

Led by double-barrelled far-right rabble-rouser Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, failed thespian nepo-baby Laurence Fox and others, and addressed on a big screen by Sieg Heil-ing billionaire Elon Musk, a crowd of more than 100,000 people marched through London to protest against immigrants. They were particularly against foreigners who were criminals and a danger to women being allowed into Britain. According to reports, some protestors wore MAGA – Make America Great Again – hats in honour of Donald Trump: a foreigner who’s a convicted criminal, and a proven danger to women, who was being allowed into Britain for a state visit the following week.

September 16th

Donald Trump landed in Britain and his hosts immediately went into full pomp-and-ceremony grovelling mode. The orange American president got a royal salute, a lunch with the Royal Family, a tour of the Royal Collection, a ‘beating retreat’ military ceremony, a ride in a gilded coach, a state banquet at Windsor Castle, and a visit to Chequers, the prime minister’s country residence, for a look at the Winston Churchill archives and a press conference.

Speaking at the state banquet, Trump declared, “…this is truly one of the highest honours of my life. Such respect for you and such respect for your country… The lionhearted people of this kingdom defeated Napoleon, unleashed the Industrial Revolution, destroyed slavery and defended civilization in the darkest days of fascism and communism. The British gave the world the Magna Carta, the modern parliament and Francis Bacon’s scientific method. They gave us the works of Locke, Hobbes, Smith and Burke, Newton and Blackstone. The legal, intellectual, cultural and political traditions of this kingdom have been among the highest achievements of mankind.”

A week later, Trump gave a speech to the United Nations and had this to say about London, capital of Britain, and Western Europe, of which Britain is a part: “And I have to say, I look at London where you have a terrible mayor, a terrible, terrible mayor, and it’s been so changed, so changed. Now they want to go to Sharia law, but you’re in a different country, you can’t do that. Both the immigration and their suicidal energy ideas will be the death of Western Europe if something is not done immediately… I’m really good at this stuff. Your countries are going to hell.”

Maybe the grovelling hadn’t worked.

From wikipedia.org / © Executive Office of the President of the US

September 17th

American late-night TV host Jimmy Kimmel was suspended indefinitely by the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), following comments he made about the assassination of Charlie Kirk. These drew the ire of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The FCC’s chair is Brendan Carr, a staunch Trump loyalist. Trump applauded Carr as ‘a great American patriot’ for his actions.

Funnily enough, in 2022, Carr had declared: “Political satire is one of the oldest and most important forms of free speech. It challenges those in power while using humour to draw more into the discussion. That’s why people in influential positions have always targeted it for censorship.” And Kirk himself once said of freedom of speech: “You should be allowed to say outrageous things.” But perhaps what they meant was political satire and outrageous things should only be expressed by people they agreed with.

September 22nd

After an uproar from practically everybody, and their granny, and their dog, the forces that’d removed Jimmy Kimmel from the airwaves backtracked. It was announced that he was being reinstated on ABC. A new episode of his show was broadcast the following evening. It achieved his highest ever ratings – 6.26 million viewers – and was viewed 26 million times on YouTube. Kimmel quipped about Trump’s likely reaction: “He might have to release the Epstein files to distract us from this now.”

In other words… The American right, which earlier in the month had worked so hard to make a martyr out of Charlie Kirk, blaming his death on the ‘radical left’ and threatening retribution against anyone who suggested he might be anything less than a saint, had inadvertently made a martyr out of Jimmy Kimmel instead.

September 23rd

Trump delivered an hour-long speech to the United Nations. Besides condemning the institution for a malfunctioning teleprompter and an escalator that stopped working – him and his missus Melania had to climb the stationary escalator, which for someone of his considerable acreage must have been hard work – and besides ranting about ‘radicalised environmentalists’ (“No more cows. We don’t want cows anymore. I guess they want to kill all the cows.”), he boasted that he’d ended seven wars: “…Cambodia and Thailand, Kosovo and Serbia, the Congo and Rwanda… Pakistan and India, Israel and Iran, Egypt and Ethiopia, and Armenia and Azerbaijan.”

In fact, two of these wars didn’t exist, two have continued in terms of ceasefire violations and ongoing bloodshed, one was a war Trump helped to start and then participated in, one was a war where one of the countries denies that Trump had anything to do with settling it, and one ended with a peace-deal that hasn’t yet been ratified.

That last war, the one Trump actually came closest to ending, was the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. Previously, at the September 18th press conference with Keir Starmer, Trump claimed to have stopped a war between Albania and Azerbaijan. And at a dinner in Vermont on September 20th, Trump announced that he’d ended a war between Armenia and Cambodia. So maybe that’s why Armenia and Azerbaijan agreed on a peace-deal. One was so busy fighting Albania, and the other so busy fighting Cambodia, that they no longer had time to fight each other.

Come to think of it, none of this was ironic. It was just moronic.

September 26th

The Ryder Cup, golf’s biennial contest between Europe and the USA, teed off at Bethpage State Park in New York State. Trump attended its opening day, making him the first sitting American president to do so. It’s fair to say that his attitude towards golf – win at all costs, even if it means getting caddies to plant new balls for you when the old ones land in inconvenient places – and his attitude towards competition generally – win at all costs, no matter what a bullying, graceless, ignorant chump it makes you look – infected the crowd. Taking their cue from their Dear Leader, they behaved like bullying, graceless, ignorant chumps for the next couple of days. They chanted “F*ck you Rory!” at Northern Irish golfer Rory McIlroy. They threw beer at McIlroy’s wife. They hurled insults at McIlroy’s fellow Irish golfer Shane Lowry about his weight. No wonder at one point McIlroy told them all to “Shut the f*ck up.”

Anyhow, Europe won the Ryder Cup by 15 to 13. That wasn’t ironic either. That was karma.

From wikipedia.org / © The White House