It’s October 31st, the day of the spooky festival known in Ireland as Samhain and elsewhere as Halloween. As is my custom each Halloween, I’ll celebrate the spirit of the occasion by posting on this blog ten of the creepiest or most unsettling pieces of artwork I’ve come across during the year. By the way, the above photos are of a house in my immediate neighbourhood in Singapore. Its inhabitants must really love Halloween.

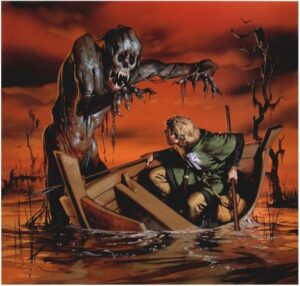

Let’s begin with a great, old-school horror illustration where an unwary boatman has an encounter with a marsh-monster. This was painted by the late Angus McBride, an artist who was born in London to Scottish parents but spent much of his professional career based in South Africa. McBride’s resume included work for the educational magazines Look and Learn (1962-82) and Worlds of Wonder (1970-75), the Men-at-Arms series from Osprey Publishing and the tabletop game Middle-earth Role Playing inspired by the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. In fact, it’s from a collection of those last illustrations – Angus McBride’s Characters of Middle-earth (1990) – that this ghoulish picture comes. The hideous beastie is actually a Mewlip, which The One Wiki to Rule Them All describes as ‘a fictional race, made up by Hobbits of the Shire, mentioned only in one poem.’

© Iron Crown Enterprises

Onto something more elegant. I love old posters and illustrations advertising that most decadent of alcoholic drinks, absinthe. These were often the work of Art Nouveau artists, most famously, Alphonse Mucha. But away from the gentle curves and nymph-like belles dames of Art Nouveau, there’s a darker school of absinthe artwork, which suggests the drink’s more sinisterly seductive and ruinous side. These feature green devils, black cats and, depicted in this painting from la Belle Epoque, a splendidly vaporous green lady-ghost. It’s entitled Absinthe Drinker and is the work of the Czech artist Viktor Oliva, who reputedly quaffed much of the stuff in Paris in the late 19th century. Absinthe Drinker now hangs in the Zlata Husa Gallery in Prague.

From wikipedia.org

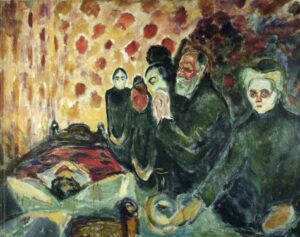

You get the impression la Belle Epoque passed by the great Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, whose paintings – most famously The Scream (1893) – often suggest he lived in a state of perpetual, nerve-jangling anxiety. During his childhood, he suffered the trauma of losing his mother and sister to tuberculosis and getting a bout of it himself when he was 13: “One Christmas Eve, when 13 years old, I lie in my bed,” he recalled. “The blood trickles from my mouth – the fever rages in my veins – fear cries out deep within me. Now, now, in just a moment, you will meet your Maker and be sentenced for eternity.” In 1893, drawing on those experiences, he painted By the Death Bed (Fever) with pastels. He would do further versions of it, with oils in 1895 and 1915 and as a lithograph in 1896. It’s the 1915 By the Death Bed (Fever) that I find most disturbing. The white-skinned, almost skull-faced woman on the right could pass for the Angel of Death, while the appropriately diseased-looking wallpaper resembles a close-up of a yellow handkerchief, into which a TB victim has just coughed globs of blood. Actually, the décor puts me in mind of one of the best horror short stories of all time, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper (1892).

From archive.com/artwork

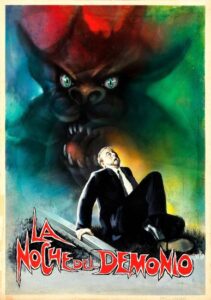

Another all-time classic horror short story is M.R. James’ Casting the Runes (1911), which taps into the fear there’s something monstrous and nasty following you, and following you, and all the time getting closer… The story was filmed as Night of the Demon in 1957, 21 years after James’ death. I think James would have approved of the creepy atmosphere and build-up created by director Jacques Tourneur, but not of big, shonky-looking demon that’s doing the following and appears at the movie’s climax. Apparently, it was shoehorned into the film by its producers, against Tourneur’s wishes. Still, I really like this colourful poster for the movie, painted by Spanish artist Enrique Mataix. Mataix produced movie posters for almost a half-century, from 1939 to 1988, including ones for Bringing Up Baby (1938), Waterloo Bridge (1940), The Glenn Miller Story (1954), Lust for Life (1956), North by Northwest (1959) and Anatomy of a Murder (1959). Yes, his Night of the Demon poster gives prominence to that silly demon, but it’s slightly blurred, which hides its shonkiness. And the surrounding, infernally psychedelic colours are striking.

From monsterbrains.blogspot.com / © Columbia Pictures

This next work, Can You Show Me the Way Home by Californian artist Brandi Milne, feels like it could be an illustration from a movie poster. Maybe one for a warped 1960s psychological thriller where children are imperiled, like Bunny Lake is Missing (1965), The Nanny (1965) or The Mad Room (1969). Of course, it also echoes that hoary old 1958 sci-fi / horror movie The Fly, whose finale has a human / fly hybrid – David Hedison’s tiny head grafted onto a fly’s body – trapped in a spider’s web, while the humungous spider crawls hungrily towards it. Rather than an attached-to-a-bug David-Hedison-head, Can You Show Me the Way Home artfully features a detached doll-head. Also, it’s disarmingly presented in a child-like palette of black, white, grey, pink and straw-yellow. Though going by the size of the doll-head, its spider must be pretty humungous too.

From dorothycircusgallery.com / © Brandi Milne

And there’s an obvious cinematic vibe – J-Horror this time – from this picture by Ohio-based concept artist David Sladek, aptly titled Waiting at the Wrong Bus Stop. It strikes a particular chord with me. During my misspent youth, I occasionally spent too long in a pub on a Friday or Saturday night and then found myself waiting for a late-night bus, in a decrepit and remote bus shelter, in the company of various unsavoury-looking characters. Though none of them ever looked as unsavoury as the characters here.

From artstation.com / © David Sladek

And now for something completely different. For depictions of the surreally ghoulish, you can’t beat Hieronymus Bosch. Here’s a detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights, the legendary triptych the Dutchman painted between 1490 and 1510. Its panels depict the paradise that’d been the Garden of Eden, the titular garden with its cavorting, amorous nudes and… hell. Obviously, the hell-panel contains the images that everyone remembers. This part of it shows a knight being devoured by what Wikipedia describes as ‘a pack of wolves’, though to me they look more that horror-story staple, rats – giant ones. No doubt the thoughts flashing through the unfortunate knight’s brain are similar to the thoughts of the first victim in James Herbert’s 1974 paperback epic, The Rats: “Rats! His mind screamed the words. Rats eating me alive! God, God help me…”

From smarthistory.org

And keeping with rats, this gleeful-looking half-human, half-rat creature never fails to give me the creeps. It’s the work of the American artist Brom, originally from Albany, Georgia. His career has included illustrating the roleplaying worlds of Dungeons & Dragons and, more recently, providing pictures for as well as writing his own horror novels. This illustration comes from his 2021 novel Slewfoot: A Tale of Bewitchery.

From bromart.com / © Gerald Brom

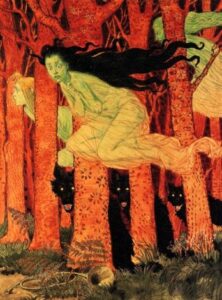

Meanwhile, proper wolves – though perhaps they’re werewolves – feature in this beautifully evocative watercolour, ink and pencil work done by the Swiss artist Eugene Grasset in 1892, Three Women and Three Wolves. I love everything about it: the trio of eerily floating women, who must be witches, or nymphs, or spirits, and the half-shocked, half-indignant way the nearest woman looks out of the picture at us; the three black wolves also looking, and laughing, out of the picture; the subtly-patterned russet trunks of the forest trees; the carpet of ferns. And what’s that lying in the bottom left-hand corner? A horn? A hunting horn? Have the wolves just been chomping on a huntsman? No wonder they look so jolly.

From wikipedia.org

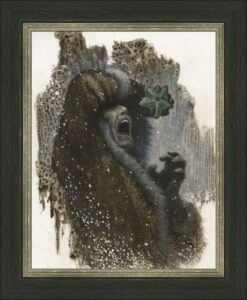

There aren’t any wolves, giant rats, giant spiders, J-Horror apparitions or any other monstrosities in this illustration by another Californian, Michael Whelan, described as ‘one of the world’s premier artists of imaginative realism’ and the most lauded artist in the history of science fiction. (He has 15 Hugo Awards under his belt for a start.) Done in acrylic, it’s an interior illustration for a Centipede Press edition of the famous H.P. Lovecraft novella At the Mountains of Madness (1931) which, as far as I can ascertain, hasn’t been published yet. It’s the pictorial equivalent of a cinematic reaction shot. But what a reaction. The screaming explorer conveys all the cosmic horror that makes this particular story, set in the wastes of Antarctica, so claustrophobic. Particularly clever are the margins of grey fur along the edges of the explorer’s garments. They’re arranged so that they resemble that most Lovecraftian of motifs – a coiling tentacle.

From dmrbooks.com / © Michael Whelan / Centipede Press

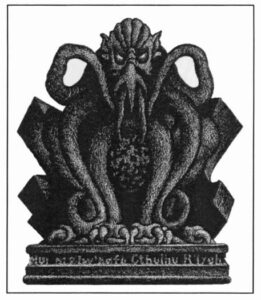

And on the subject of H.P. Lovecraft… I traditionally feature ten scary pictures in these annual Halloween posts. But this year, here’s an extra one, an eleventh, in honour of the legendary New Jersey artist Stephen Fabian, who sadly died in May this year (admittedly at a grand old age of 95). I admire the black-and-white interior designs he did for a 1998 volume entitled In Lovecraft’s Shadow, which is a collection of short stories not by Lovecraft but by his pen-friend and posthumous publisher August Derleth. Unfortunately, reproducing an entire illustration on this page would mean reducing it and shedding some of its intricate detail. So here’s part of an illustration for the 1948 Derleth short story Something in Wood. It shows a statue of Lovecraft’s ghastliest and most famous deity, Cthulhu, looking tentacle-y and baleful, as ever.

© Mycroft & Moran / Stephen E. Fabian Sr

Happy Halloween!