© United Artists / Colombia Pictures / MGM

Written and directed by John Milius, released in 1975 and very loosely based on a real-life incident that occurred in 1904, The Wind and the Lion is a tale of derring-do in the Moroccan Rif combined with political intrigue in Washington DC. I first saw it when I was in my late teens and appropriately for a film with ‘wind’ in its title – that’s wind of the meteorological, non-flatulent variety – it blew me away.

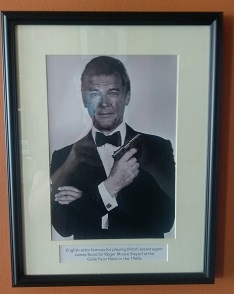

Following the death of its star Sean Connery last year, I decided to watch The Wind and the Lion again. I felt slightly trepidant doing so, as there’s more than one film that I admired in my youth but found less-than-brilliant when I saw it again at a more mature age. A prime example is Robert Altman’s 1970 comedy about the Korean War, M*A*S*H, which once upon a time seemed exhilarating in its irreverence and anarchy, but nowadays strikes me as juvenile and mean-spirited.

The Wind and the Lion’s opening sees Connery’s character, master-brigand Mulai Ahmed el Raisuli – the Raisuli – lead a raid on the Moroccan home of wealthy American widow Eden Pedecaris (Candice Bergen) and abduct her and her young children (Simon Harrison and Polly Gottesman). My hopes that I’d hang onto my previous high opinion of The Wind and the Lion took a blow at this early point. It isn’t so much the fact that Eden’s houseguest at the time, Sir Joshua Smith (played by Billy Williams, not an actor but the movie’s cinematographer, who’d later win an Academy Award for his work on Richard Attenborough’s 1982 epic Gandhi), gallantly fights off the attacking hordes, is killed and then despite his heroism is barely mentioned by the Pedecarises or anyone else during the rest of the film. No, it’s the fact that Eden, understandably upset by what’s happened, laughs in scorn when the Raisuli is thrown off a recalcitrant horse – and the Raisuli reacts by whacking her across the face. “I am Raisuli,” he snarls. “Do not laugh at me again.”

Yes, it’s 1904, when misogyny was a universal and unremarked-upon fact of life. (It still is in many places, of course.) But Connery’s later years and posthumous reputation were tainted by allegations of domestic abuse against his ex-wife Diane Cilento and by troubling comments he’d made about the acceptability of slapping women. This moment in The Wind and the Lion is a dismaying reminder of that.

The Raisuli and his men carry the Pedecarises off to their camp in the Rif, beyond the reach of the Moroccan authorities. His motive for kidnapping them is to damage Morocco’s Sultan Abdelaziz. By issuing an extravagant ransom demand, he hopes to embarrass the Sultan, provoke the Americans and generally stir up trouble. The Sultan’s uncle is the wily Bashaw of Tangier, the Raisuli’s brother, and he deeply resents how this wing of his family have allowed their country to become humiliatingly and corruptingly mired in foreign influence. As the Bashaw himself admits at one point: “I have been threatened by the French, the Germans, the English… Yes, we have French infantry and German cavalry. Our currency is Spanish. But my nephew is the Sultan of Morocco. As it is, it shall be.”

The Bashaw, incidentally, is played by the Polish character actor Vladek Sheybal, who was memorable as the villainous Kronsteen in Connery’s second Bond outing From Russia with Love (1963). But it has to be said that the strapping, hairy Connery and the sleek, lupine Sheybal look as much like brothers as Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito did in Ivan Reitman’s Twins (1988).

© United Artists / Colombia Pictures / MGM

Happily, once the main narrative of The Wind and Lion gets underway, the film becomes as good as I remembered it to be. Connery and Bergen make the scenes featuring Eden Pedecaris and the Raisuli a joy. She gradually shifts from being deeply unimpressed by him – “It is not my intention to encourage braggers,” she tells curtly him after he’s given a windy introduction calling himself ‘Raisuli the Magnificent’ and ‘the true defender of the faithful’ with the ‘blood of the prophet’ in his veins – to feeling affection for the twinkly-eyed old rogue. Likewise, Connery’s admiration for her increases, although the banter between them never quite loses its edge. After they start to spend the evenings playing chess, she warns him, “You are in a lot of trouble! You should never have moved that knight or kidnapped me. Both will see you undone.” He responds, “It is not I who determine the outcome of events. It is the will of Allah…”

Meanwhile, the Pedecaris children, removed from an upper-class Western world of manners, gentility and stuffiness, begin to have a whale of a time. For the boy, William, hanging out in a desert camp with the Raisuli and his sword-wielding, rifle-popping Berber militia is like Tom Sawyer’s dream of running away from home and becoming a pirate made real.

But this is only half of the story of The Wind and the Lion. For on the far side of the Atlantic, President Teddy Roosevelt (Brian Keith) is seeking re-election. He seizes upon the incident as an opportunity to show the voters his mettle, although his Secretary of State John Hay (John Huston) is less keen on the idea. The garrulous and ebullient Roosevelt has his consul in Morocco (Geoffrey Lewis) and a US military force headed by an admiral (Roy Jenson) and a marine captain (Steve Kanaly) stage what nowadays would be called an intervention. A squad of marines and sailors blast their way into the Bashaw’s palace in Tangiers, determined to knock heads together so that some sort of deal is reached and the Pedecarises are freed. This is regardless of local sensibilities and the interests of the European colonial powers with fingers in the Moroccan pie.

A bargain is made and the three Pedecarises are released into the custody of a group of US marines headed by Kanaly’s character, Captain Jerome. But the Sultan’s Moroccan soldiers and their German allies capture the Raisuli, going against what was agreed. Thus, Eden, his erstwhile prisoner, has to persuade Jerome and his men to rescue him, so that the deal made in Roosevelt’s name is fully honoured…

Images of gung-ho Americans stomping into foreign lands they don’t properly understand, shooting first and asking questions later, trying to get the job (as they see it) done irrespective of local complexities, were not, it’s fair to say, popular in liberal mid-1970s Hollywood just after the Vietnam War. And John Milius himself, co-writer of Apocalypse Now (1979) with Francis Ford Coppola, was obviously aware of the omnishambles Vietnam had been. However, with The Wind and the Lion, he seems to hark back longingly to simpler times when America could do this sort of thing with fewer complications and consequences. He particularly idolizes Teddy Roosevelt for embodying all the things he believes America should be about. Roosevelt has brains, yes, but he has brawn too and is plain-speaking and no-bullshitting, and is none the worse for that.

© United Artists / Colombia Pictures / MGM

This adulation comes to the fore in a few scenes where Roosevelt joins a hunting party that shoots a grizzly bear and then he has the big, fearsome beast stuffed and mounted. “The American grizzly,” he tells a reporter, “is a symbol of the American character: strength, intelligence, ferocity. Maybe a little blind and reckless at times, but courageous beyond all doubt. And one other trait… Loneliness. The American grizzly lives out his life alone. Indomitable, unconquered, but always alone. He has no real allies, only enemies, but none of them as great as he.” Fair enough, you find yourself thinking – but if the grizzly bear is as noble as old Teddy claims it is, why did he have the poor bloody thing shot in the first place?

To be fair, the film gives a more rounded portrayal of Roosevelt than that. He’s shown to be somewhat pompous and smug, annoying in his loquaciousness, and clearly a scheming sort. I wonder, though, how much of this is due to Brian Keith’s performance rather than to Milius’s script.

What redeems the film politically – at least, if you’re a left-wing pinko like me – is the fact that as it progresses, Keith’s Roosevelt and Connery’s Raisuli, though they never get to meet, feel a growing respect and even kinship for each other. By the film’s close, the Raisuli has penned Roosevelt a letter, which says: “…you are like the wind and I like the lion. You form the tempest. The sand stings my eyes and the ground is parched. I roar in defiance but you do not hear… I, like the lion, must remain in my place. While you, like the wind, will never know yours…”

If you’re going to have movies full of jingoistic American nonsense, at least have ones like this, where the American protagonists don’t see foreigners as drone-like commies, gooks or towel-heads but as fellow human beings with equivalent amounts of nobility and courage. It just grieves me that a decade later, Milius had abandoned all attempts at nuance and was directing unashamedly right-wing and brainless shite like Red Dawn (1984).

Overall, then, I’m pleased and relieved to say that The Wind and the Lion still holds up well. Milius directs with aplomb. His orchestration of the sequence where the Americans storm the Bashaw’s palace is worthy of Sam Peckinpah while the desert scenes, accompanied by Jerry Goldsmith’s sumptuous and yearning score, are frequently gorgeous. Brian Keith and Candice Bergen are excellent and Connery, intoning such great lines as “Ignorance is a steep hill with perilous rocks at the bottom,” or “If I miss the morning prayer, I pray twice in the afternoon – Allah is very understanding,” or finally, “I’ll see you again, Mrs Pedecaris, when we’re both like golden clouds on the wind!”, has never been better.

Although how this Moroccan Berber brigand ended up speaking with such a mellifluous brogue is a mystery. Perhaps his English teacher came from Edinburgh.

© United Artists / Colombia Pictures / MGM