© EMI / Elektra Records

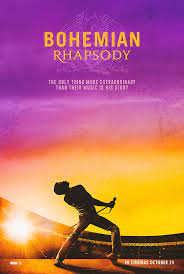

Back in 2018, I found myself in a Colombo pub one evening having a blether with Suresh De Silva, the vocalist and co-founder of the Sri Lankan heavy metal band Stigmata. Within seconds of the start of our conversation De Silva had asked me if I’d seen Bohemian Rhapsody, the movie biopic of the 1970s / 1980s rock band Queen, which’d been released in Colombo cinemas a few weeks earlier. The unexpectedness of the question threw me a little. It also reminded me of the hugeness of the phenomenon that is Queen.

It’s a phenomenon that transcends place. National boundaries seem not to matter when it comes to liking Queen. Meeting a Sri Lankan heavy metaller in 2018 who wanted to talk about the band wasn’t my first experience of this. I remember working long ago at a language school in the UK that had weekend discos for its kids. At one point there were a lot of self-consciously trendy and streetwise teenagers from Milan at the school and the DJ who oversaw that weekend’s disco thought he’d please his audience by playing then-modish big beat, drums and bass, UK garage and hard trance tunes. But he ended up nearly causing a riot. What did those trendy Italian teens want him to play? I Want to Break Free by Queen. All bloody evening.

Their popularity also transcends time. They remain fabulously popular today even though they’ve been creatively inert since 1991, when their singer Freddie Mercury passed away from AIDS.

I find this interesting because back in the days when they were a properly functioning band, friends of mine who considered themselves serious and knowledgeable connoisseurs of music would tell me that though they tried to be broad-minded, they just couldn’t stomach bloody Queen, whom they saw as purveyors of bloated, corny, stomp-along, guitar-twiddling shite. Meanwhile, other folk, who bought at most three CDs a year and barely knew the difference between Elvis Costello, Elvis Presley and Reg Presley – the majority of the British population in other words – believed Queen were the absolute bees’ knees.

Incidentally, it seemed ironic to me how popular Queen were in the 1970s and 1980s among guys who were unreconstructed, macho and laddish and who, in all likelihood, were pretty homophobic too. They were liable to punch you in the face if you suggested they were into anything that might be classified as ‘gay’ culture. But after a few moments of hearing the unashamedly camp Freddie Mercury crooning, “Oooh, you make me live… / Oooh, you’re my best friend!”, they’d be hugging each other, shedding sentimental tears and singing along in emotion-cracked voices.

© 20th Century Fox / Regency Enterprises / GK Films

I wasn’t greatly impressed by Bohemian Rhapsody when I caught up with it, sometime after speaking to Suresh De Silva. It takes many liberties with the truth. For example, the band weren’t on the wane before their barnstorming appearance at the 1985 Live Aid concert at Wembley Stadium, which the film claims pulled them back from the brink. On the contrary, during the previous year and following the release of their 1984 album The Works, I remember them being as popular and prominent as ever. And there was no big emotional moment before they took the Wembley stage when Freddie told his bandmates he was HIV positive. In reality, he didn’t know this until 1987.

Meanwhile the film airbrushes away the band’s real-life moral warts and carbuncles. We get nothing about, for instance, their misguided and money-fuelled decision to play at the Sun City Super Bowl in Bophuthatswana, South Africa, at the height of the apartheid era. This act of unprincipled greed earned them a ban by the British Musicians’ Union. Also doused in a tankerload of whitewash is the issue of Freddie’s promiscuity. In 1984, the real Freddie bragged to the DJ Paul Gambaccini with hedonistic and, considering the times, reckless abandon: “Darling, my attitude is ‘f**k it’. I’m doing everything with everybody.” But in Bohemian Rhapsody he’s presented as a victim, insecure about his sexuality and led astray by his personal manager Paul Prenter, who introduces him to a world of partying, orgy-ing and general dissolution.

Still, the sequence in the film with Mike Myers as a (fictional) record executive called Ray Foster, who’s aghast at the idea that Bohemian Rhapsody-the-song should be released as a single, is funny. “It goes on forever. Six bloody minutes!” To which Freddie retorts: “I pity your wife if you think six minutes is forever.”

Personally, I thought 1970s Queen were great. They produced albums like Sheer Heart Attack (1974), A Night at the Opera (1975), A Day at the Races (1976) and News of the World (1977) that were studded with classic songs and, though they sometimes felt all over the place stylistically, were admirable for trying to explore a wide range of musical genres, everything from music-hall singalongs and salsa-y Spanish guitar workouts to blues and jazz and even, with 1974’s Stone Cold Crazy, nascent speed metal. The rip-roaring Death on Two Legs, which kicks off A Night at the Opera, is one of my favourite songs ever.

But for me they seemed to lose their creative mojo at the beginning of the 1980s. The last song by them that I liked was probably their 1981 duet with David Bowie, Under Pressure. Actually, I didn’t think much of Under Pressure at the time, but it’s grown on me since then. It’s certainly a zillion times better than Vanilla Ice’s dire 1990 single Ice Ice Baby, which appropriated Under Pressure’s memorably nagging bassline. (I remember being at a Saturday-night disco in my hometown in Scotland – the clubhouse of Peebles Rugby Club to be precise – when the DJ put on Ice Ice Baby. The bassline started and everyone cheered and hurried onto the dance floor, thinking it was Queen and David Bowie. Then the lyrics started: “Yo! Let’s kick it! Ice, ice baby…” Everyone threw up their hands in horror and shouted, “Och, shite! It’s Vanilla Ice!” The dance floor immediately cleared again.)

Anyway, a few days ago, taking advantage of the fact that Sri Lanka’s most recent Covid-19 lockdown has been lifted, I went for a walk and ended up at the area where Colombo’s Dehiwala Canal meets with the Indian Ocean. It’s a pleasantly grassy and leafy neighbourhood although, thanks to the condition of the water in the canal, it’s a bit smelly too. And lo and behold, on a wall standing at the canal’s southern bank, I saw further evidence of the global love for Queen.

Yes, it was a mural of Freddie Mercury in his moustached, short-haired, white-vested Live Aid incarnation, which presumably someone had painted after seeing Bohemian Rhapsody in 2018.

As I’ve suggested in this post, I have mixed feelings about Queen overall. But the fact that in the 21st century a Sri Lankan graffiti artist was inspired to paint their iconic vocalist and master showman on an out-of-the-way, canal-side wall makes me feel strangely happy.