On Friday, August 16th, two friends and I ventured into the Foochow Building on Singapore’s Tyrwhitt Road to experience Hardcore Island 2: A Fine City, the latest extravaganza staged by the Singapore Pro-Wrestling (SPW) association. We’d been laggardly in getting there, having supped a beer too many in a nearby pub, and arrived near the end of the evening’s first bout: one between local wrestlers CK Vin and Emman. As we entered the hall where the action was taking place, we were greeted by the sight of CK Vin throttling Emman with a folded chair. He’d put the back chair-frame over Emman’s head and had the rear edge of the seat deep in his throat. Unsurprisingly, soon afterwards, Emman submitted.

This, it transpired, was a ‘chairs match’ – which, Wikipedia informs me, is a contest where “only chairs can be used as legal weapons, but the only way to win is by pinfall or submission in the ring.” I liked the publicity blurb with which the SPW presaged CK Vin and Emman’s fight: “You’ll want to get to your seats now before the wrestlers take them all for weapons.”

© Singapore Pro-Wrestling

Before I moved to Singapore, it’d been a long time since I watched a professional wrestling match. In fact, I hadn’t been a fan of the sport since my boyhood in Northern Ireland. This was when World of Sport, Independent Television’s Saturday-afternoon sports show, would always have a four o’clock slot devoted to what people in those days simply called ‘the Wrestling’. Watching the Wrestling on TV, I quickly became obsessed with such larger-than-life figures as Les Kellett, Mark ‘Rollerball’ Rocco, Tally Ho Kaye, Jim Breaks, Mick McManus (catchphrase: “Not the ears! Not the ears!”), Big Daddy (catchphrase: “Easy! Easy! Easy!”), the gargantuan (six-foot-eleven, 685 pounds) Giant Haystacks and the mysterious, masked Kendo Nagasaki who claimed to be channelling “the spirit of a samurai warrior who, 300 years ago, lived in the place that is now called Nagasaki.” (He himself lived in Wolverhampton.) But I never got into the brasher, showier and slightly more glamorous pro-wrestling spectacles served up in subsequent decades by America’s World Wrestling Federation (WWF), later World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE). And though for most of the 1990s I lived in Japan, I didn’t get into the super-popular New Japan Pro-Wrestling and All Japan Pro-Wrestling promotions either.

But I’d always enjoyed wrestling movies, such as Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler (2008) or Stephen Merchant’s Fighting with my Family (2019). Okay, Mr. Nanny (1993) with Hulk Hogan not so much. And it often occurred to me that I’d like to see some live bouts. So, last year, when a mate told me of the existence of the SPW and invited me to one of their events, I thought, why not?

Anyway, back to tonight’s proceedings. The second bout on the bill involved two more local wrestlers, Destroyer Dharma and Kentona – the former defeating the latter with a pinfall, which in wrestling jargon is when you hold your opponent’s shoulders against the ring-floor long enough for the referee to count to three. Not for the last time that evening, the fighting spilled out of the confines of the ring and into the surrounding hall – much to the glee of the spectators, always happy to get a close-up view of the carnage. I should say that the crowd was a pleasing mix of young and old, male and female, and Singaporeans and foreigners. It was a far cry from the audiences I remember watching the 1970s British wrestling, which seemed to consist mainly of demented old grannies who’d hobble forward and club Mick McManus with their handbags whenever he was against the ropes.

The third battle tonight was a hotly anticipated one between Singapore’s Jack ‘N’ Cheese and the Gym Bros, who hail from Pattaya in Thailand. Jack ‘N’ Cheese are BGJ, aka Jack Chong, described on his Instagram page as the ‘Beast of Benevolence’; and the Cheeseburger Kid, whose yellow cowl-mask makes him resemble a jaundiced Deadpool. The latter has become a popular fixture of Singapore’s pro-wrestling world and tonight it looked like he had a mini-fan-club in tow – a small but voluble group in yellow T-shirts at the front of the crowd who cheered on his every move. It has to be said of their opponents, the Gym Bros, that they were at least a wee bit camp. One had a headful of Debbie-Harry-style blonde hair and wore white spats up to his knees. The other sported a weedy moustache and was clad in tight pink shorts whose contours left little to the proverbial imagination.

To the delight of everyone – bar the Gym Bros – Jack ‘N’ Cheese won the bout through another pinfall. And nobody was more delighted than the Cheeseburger Kid, who reacted to victory by leaping up into BGJ’s arms and posing there for the cameras.

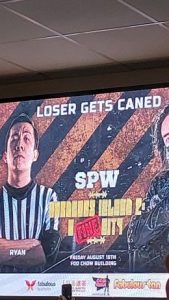

Next came a tussle between two more wrestlers from the SPW roster: Bryson Blade, wearing bad-boy black-leather pants, and Referee Ryan, who, appropriately for a person sometimes working as a referee, was attired in a more sober costume of black and white. This was billed as a ‘Loser Gets Caned Match’. The blurb for it declared, “…the loser will be forced to take a lashing with a Singapore cane post-match! Gather round, people! You’re about to be taken back, school assembly style.” That references the fact that Singapore not only allows caning as a judicial punishment – a maximum of 24 strokes for a range of criminal offences – but also as a corporal punishment in schools, for male pupils who commit serious offences. (Actually, it took me back, since corporal punishment was still legal in Northern Irish schools in the 1970s and I got caned a few times, though not with a Singaporean rattan cane but a beechwood one.)

Eventually, Referee Ryan lost through a pinfall and ended up receiving ‘five of the best’. I wasn’t sitting near enough to the ring to be sure, but I suspect the cane-strokes may not have landed with the fullest possible force.

Following a 15-minute interval, bout number five saw another pair of Singaporean wrestlers in action, Zhang Wen and Riz. The former won, again by a pinfall. Then came a trio of female wrestlers slugging it out in a three-way battle. Representing Singapore in this scrap was the formidable Alexis Lee, who also goes under the moniker ‘Lion City Hit Girl’ and is the city-state’s very first lady pro-wrestler. The Straits Times newspaper recently described her as “…a rampaging figure of death, who will stomp and slam her opponents swiftly and ruthlessly.” I assume the Straits Times writer got the ‘figure of death’ idea from the white skull-make-up that covers half her face and her costume of tank-top, shorts and leggings patterned with bones and ribs. Her foes tonight were two Japanese wrestlers, Miyu ‘Pink Striker’ Yamashita and Koya Toribami. I know tori is the Japanese word for ‘bird’, which may explain why the latter fighter turned up in an elaborate, beaked bird-costume.

After a hard-fought contest – at one point the three of them were engaged in a sort of treble bearhug, with the bird-themed Koya Toribami caught in the middle like a piece of chicken in a chicken sandwich – Alexis Lee won with a pinfall. Afterwards, outside the ring, she posed defiantly with a glass of beer, which she’d definitely earned.

The seventh and final bout was an all-Singaporean affair pitching two teams of three wrestlers against each other – the Horrors, consisting of Aiden Rex, Dr Gore and Da Butcherman, and the Midnight Bastards (billed in some quarters as ‘State of Bastards’), consisting of RJ, Mason and Andruew Tang, aka the Statement. Despite being the co-founder of and head coach at SPW, Tang / the Statement has a villainous ring persona: “Embrace the Statement or I will make a statement out of you!” This was billed as an ‘Xtreme Rules’ match, which meant there were no rules. Not only chairs could be utilized as weapons, but also tables, a big wooden board that someone dragged out from under the ring, and even a stepladder. Yes, I’d noticed how that stepladder had been parked all evening at the far end of the hall and wondered when it was going to come in handy. It did when the spiky-mohawked Da Butcherman clambered up one side of it, and Andruew Tang, in gold-streaked trousers, clambered up its other side, and they faced off at the top.

At another point, the wrestlers hurriedly assembled, IKEA-style, a table in the ring. Then someone poured dozens of small, multicoloured, plasticky things across the tabletop. And soon after, an opponent got slammed down on the covered table, on his back. Ouch! One of my friends thought the plasticky things might be drawing pins. I had a horrible suspicion, though, that they were pieces of Lego. I remember how much my foot hurt after I stepped on a Lego-piece as a kid, so having your back thumped down against a whole table’s worth of those must be hellishly sore.

Anyway, thanks to yet another pinfall, the Horrors emerged victorious. And that was it for the night. Just to make the experience a little bit sweeter, on our way out, we encountered the Cheeseburger Kid standing at the Foochow Building’s entrance. We told him how much we’d enjoyed his fight and he seemed to genuinely appreciate our warm words.

Certain sports purists might quibble about the tongue-in-cheek, even corny nature of some of what was on show tonight. But the SPW’s get-togethers never fail to provide fun and excitement. The city / island state of Singapore has a reputation for being a calm, ordered and well-run place, but it’s nice to think that there’s a little part of it where, thanks to the SPW, for an occasional few hours, good-natured anarchy takes over. Where it becomes an anything-goes ‘lion city’ or a riotous ‘hardcore island’. Where – to borrow a quote from Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist (2009) – “Chaos reigns!”