© Penguin Classics

Another post for Halloween…

Even if the American horror, science-fiction and mystery writer Ray Russell hadn’t done any writing, it’s likely he still would have had an impact on one of his preferred genres.

In the 1950s, after serving in the wartime US Air Force, studying at the Chicago Conservatory of Music and working for the United States Treasury, he became fiction editor for Hugh Hefner’s Playboy magazine. Playboy was an odd combination of smutty pictures of hot ladies and seriously well-written stories and articles. The magazine’s detractors have dismissed this as a cynical ploy on Hefner’s part, propagating the idea that you could simultaneously be an unsavoury male lech and a connoisseur of the literary and intellectual. Hence, by perusing the latest fiction by Philip Roth or an interview with Jean-Paul Sartre, its readers didn’t have to feel bad about jerking off to a picture of the Playmate of the Month a few pages earlier.

Whatever. During the 1950s, Russell must have kept many horror and fantasy writers, such as Robert Bloch, Richard Matheson, Ray Bradbury and Charles Beaumont, afloat by regularly buying their short works and printing them in Playboy‘s glossy – if sometimes ejaculation-splattered – pages. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, those guys had moved onto television and were writing scripts for shows like The Twilight Zone (1959-64) and the Boris Karloff-hosted Thriller (1960-62). (In Robert Bloch’s case, his 1959 novel Psycho also became something of a hit when it was adapted for the cinema screen by a chap called Alfred Hitchcock). These shows imprinted themselves on the DNA of the kids watching them, who occasionally grew up to be popular filmmakers, like Steven Spielberg, or popular novelists, like Stephen King.

In effect, indirectly, Russell helped cultivate an unsettling, mid-20th-century American gothic. This was one in which the world suddenly and inexplicably turned dark and weird for the citizens of post-war, suburban America – for office-bound men in grey-flannel suits, dutiful housewives in nipped-in-at-the-waist housedresses, wholesome kids playing behind white picket fences. And it’s one whose influence is still felt today.

But it’s Ray Russell the writer, rather than the editor, whom I want to discuss here. I’ve just read a collection of his short stories, first published in 1985 and now reprinted as a ‘Penguin Classic’, entitled Haunted Castles. Yes, I bet nobody working for Penguin Books back in 1985 imagined their prestigious publishing company would one day consider a book called Haunted Castles a ‘classic’. Its seven stories show Russell’s love for a different type of gothic fiction – the full-blooded, 19th-century variety exemplified by such books as Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer (1821), Sheridan Le Fanu’s In a Glass Darkly (1872) and, of course, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

Russell’s tales here take place in a world of wild, sparsely-populated mountains and forests, fearsome thunder-and-lightning storms, nightmarish coach-rides and remote settlements inhabited by superstitious villagers. And, as the collection’s title suggests, castles. Each one is a “vast edifice of stone” exuding “an austerity, cold and repellent, a hint of ancient mysteries long buried, an effluvium of medieval dankness and decay.” In fact, four of these stories feature castles and they’re all equipped with torture chambers: “There stood the infernal rack, and branding irons and thumbscrews, and that grim table called in French peine forte et dure, whereon helpless wretches were constrain’d to lie under intolerable iron weights until the breath of life was press’d from them.”

Occupying the first two-thirds of the book are three novellas that are frequently regarded as a trilogy, though they don’t have anything in common apart from their gothic settings and trimmings and the fact that they have single-word, polysyllabic titles beginning with ‘s’: Sardonicus, Sagittarius and Sanguinarius.

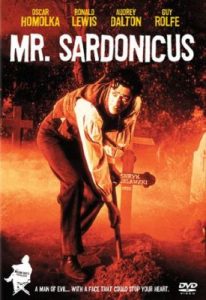

© Columbia Pictures

Kicking off the proceedings is Sardonicus, Russell’s best-remembered story. It’s told in the first-person by a 19th-century London physician called Sir Robert Cargrave, who specialises in treating muscular disorders. The title character summons him to – surprise! – his castle in ‘a remote and mountainous region of Bohemia’. Sardonicus suffered a nasty mishap in his youth. Following his father’s funeral, he discovered that prior to his death the old man had purchased a winning lottery ticket. Inconveniently, the ticket was pocketed in his burial clothes. The avaricious Sardonicus dug up his father to retrieve it, and claim the attendant fortune, but paid a hideous price. Seeing a terrifying death’s-head grin on his parent’s decaying face, he was so traumatised that his facial muscles froze and fixed his mouth in an identical, grotesque rictus. Now resembling a 19th-century version of the Joker in Batman, he tasks Cargrave with finding a cure for his affliction.

Channelling Dracula with its setting and Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera (1909) with its disfigured central character, Sardonicus benefits from both an irresistible set-up and Russell’s knowingly-florid prose-style. Also, he manages to sustain the reader’s sympathy for Sardonicus despite it becoming clear early on that he’s an evil shit who probably got what he deserved. Sardonicus’s unfortunate wife is someone Cargrave once loved from afar, and the smiley-faced cad soon makes clear to the physician that unspeakable things will be done to her if he fails in his mission.

Meanwhile, Sagittarius and Sanginarius channel other macabre literary and historical characters. With Sagittarius, it’s the dual personage described in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), though the setting isn’t Victorian London but decadent fin-de-siecle Paris – well, Paris in 1909, to be exact. Russell has a lot of fun evoking the city’s simultaneously sophisticated and sleazy theatrical world at the time, though when the Jekyll-and-Hyde trope surfaces, it’s not difficult to guess how the story will end.

Sanguinarius focuses on Elizabeth Bathory, the notorious 16th / 17th-century Hungarian countess who allegedly bathed in the blood of hundreds of murdered girls and women, believing it was a beauty treatment that’d hold the ravages of old age at bay. Interestingly, Russell’s take on the legend depicts Bathory as, initially at least, an innocent victim. The goodness gets gradually squeezed out of her, and she becomes corrupted, by an evil entourage around her. Russell also downplays the idea that she bathed in blood to stay young. Rather, the slaughter is mostly fuelled by sheer badness, by the thrill of being ‘steep’d… in reeking devilish rites, and vilest pleasures… sharing both dark lust and blame.”

Of the other stories, Comet Wine is the most substantial. Set in a community of composers and musicians in 19th-century St Petersburg, this one draws on the Faust legend and reflects the love Russell – a student at the Chicago Conservatory of Music – had for classical music. The remaining three pieces, The Runaway Lovers, The Vendetta and The Cage, are comparatively brief affairs and are best described as gothic fairy stories. But each comes with a nasty barb in its tail.

Reading these stories, there’s a sense of Russell having his cake and eating it. He describes horrible, bloody, perverted goings-on in stylised prose and with obvious relish, but at the same time doesn’t go into detail and rub our noses in the gore. Elizabeth Bathory merely laments, for example, about “the manner by which these hapless prisoners were put to death: not with the swift, blunt mercy that is dealt even to dumb cattle, but by prolong’d and calculated tortures, which I have not stomach to set down here, so degraded and inhuman were they.” A fine line is trod between the erudite and the sordid – a line that, come to think of it, Hugh Hefner would have approved of.

© Santa Clara Productions / American International Pictures

Incidentally, Russell also wrote for the movies but, sadly, no one properly managed to capture his flamboyant gothic visions onscreen. He scripted a film version of Sardonicus in 1961, with the title slightly adjusted to Mr Sardonicus. The film terrified me when I saw it on late-night TV at the age of ten. However, as it was directed by William Castle, a filmmaker more fondly remembered for the outrageous gimmicks with which he publicised his movies – plastic skeletons flying above cinema audiences’ heads in The House on Haunted Hill (1959), special ‘Illusion-o’ viewing glasses to allow audiences to see the ghosts of the title in 13 Ghosts (1960), a 45-second ‘fright-break’ near the end of Homicidal (1961) so that cinema-goers who couldn’t handle the horror could flee the auditorium (and get a refund on the way out) – rather than for the quality of the movies themselves, I imagine it wouldn’t stand up well today.

Around the same time, Russell penned scripts for two directors who’d recently made their names pioneering a newer, bolder, more vivid form of gothic-horror cinema – Terence Fisher, who’d helmed Hammer Films’ revivals of Dracula and Frankenstein, and Roger Corman, who’d launched a series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories for American International Pictures. The results, alas, represented neither director at their best. Russell wrote The Horror of It All (1964) for Fisher while he was moonlighting from Hammer and working for the low-budget Lippert Films. A horror-comedy about an oddball family getting murdered one-by-one in a dilapidated mansion, it was evidently designed to cash in on a remake, released the year before, of the 1932 classic The Old Dark House. (Confusingly, 1963’s Old Dark House remake had been produced by Hammer and directed by William Castle.) Again, I found The Horror of It All scary enough, and funny enough, when I saw it as a ten-year-old, but I hate to think what it would seem like now, 48 years on.

Russell scripted an Edgar Allan Poe adaptation for Roger Corman, 1962’s The Premature Burial. It has its moments but lacks the flair of Corman’s best Poe movies like The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) or Masque of the Red Death (1964). This is partly due to it not having the energising presence of Corman’s usual Poe-movie star, Vincent Price. And it’s hamstrung by a lame ending.

I prefer a non-gothic film Russell wrote for Corman, the sci-fi chiller X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963). This is about a scientist, played by Ray Milland, who experiments on his own eyes and ends up seeing beyond the visual spectrum that’s perceptible to humans. Nothing good comes of this, of course. Milland’s increasingly penetrative vision goes from letting him see though clothing – hence a party scene where, to his bemusement, the dancing revellers appear to be cavorting in the nude – to letting him see the distant edges of the universe, where horrible things lurk. How one reacts to the film today depends on how one reacts to the special effects that Corman, a famously thrifty filmmaker, deploys to represent Milland’s visions. They vary from psychedelic patterns and filters to (when he’s peering into human bodies) flashes of what are obviously photos and diagrams taken from human-anatomy manuals. The effects are either desperately ingenious or just plain desperate, depending on your attitude. Still, the film cultivates an effective mood of cosmic horror and the ending is nightmarish in its logic.

Ray Russell died in 1999, before there’d been a truly impressive cinematic version of his work. Actually, there still hasn’t. But returning to Haunted Castles… I notice that the forward to my edition of it has been written by none other than the Oscar-winning Mexican director Guillermo Del Toro, who specialises in making horror and fantasy films.

So… How about it Guillermo?

From penguinrandomhouse.com / © Charles Martin Bush