© Renard Press

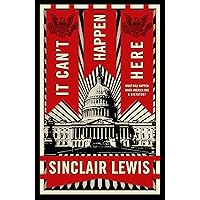

Nowadays, Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here (1935) feels like a story of alternative history, exploring what would have happened in the USA if the historical timeline had taken a twist in the mid-1930s it didn’t actually take. But when Lewis wrote it, the real timeline and his imaginary one were in the future. He was peeking ahead to the presidential election of 1936, one year after his novel’s publication, and wondering, “What if…?” In its original context, then, It Can’t Happen Here was a work of science fiction, though the future imagined was so barely ahead of the present that it probably didn’t seem like that.

It gives me no pleasure to report that reading the book in the middle of 2025, with the USA sliding remorselessly towards authoritarianism under the presidency of Donald Trump, It Can’t Happen Here doesn’t feel dated. No, it’s surely more relevant than ever.

The novel explores what could have happened if the 1936 election hadn’t been won by Franklin D. Roosevelt – who in fact won it resoundingly, garnering over 60 percent of the popular vote and securing over 98 percent of the electoral college. In Lewis’s version of events, the presidency is won by a populist maverick called Berzelius ‘Buzz’ Windrip. It’s commonly assumed Lewis based Windrip on the controversial Louisiana governor and US Senate member Huey Long. In an ironic twist of fate, Long was assassinated one month before It Can’t Happen Here was published. The son-in-law of a political rival shot him, though it’s been claimed Long actually died of a wound from a ricocheting bullet fired by one of his trigger-happy bodyguards, who immediately responded to the attacker by pumping him ‘full of lead’.

Early on in It Can’t Happen Here, we get to read Buzz Windrip’s campaign manifesto, The Fifteen Points of Victory for the Forgotten Men. This is a grab-bag of crowd-pleasing promises – the government giving every family 5000 dollars a year (point 11) while wealth being capped at 3,000,000 dollars per person (point 5) – and nakedly racist, reactionary and jingoistic rhetoric. You have to swear allegiance to the New Testament and the flag if you want a job in the professions (point 4), threats are made against the Jews (point 9) and blacks and women are disenfranchised (points 10 and 12 respectively). Oh, and there’s a sneaky final point, number 15, wherein Congress and the Supreme Court have to cede all authority to the Presidency.

The manifesto is popular enough to put Windrip in the White House and, thereafter, the USA experiences a rapid fascist takeover similar to the one Hitler engineered in Germany in 1933-34. Windrip soon has his own militia / secret police making sure everyone toes the line, media, educational and economic institutions are bullied into acquiescence, and opponents, dissenters and anyone else the regime takes a dislike to are herded into concentration camps – that’s what the novel calls them, several years before the Nazis made the term ‘concentration camp’ synonymous with evil on an industrial scale.

The country’s lurch into dystopia is seen through the eyes of Doremus Jessop, a 60-year-old, liberal-minded editor of a smalltown newspaper in Vermont. Jessop finds out the hard way that the new regime doesn’t take kindly to criticism – he pens a scathing editorial, which leads to an altercation with some officials, which results in his son-in-law being executed. Afterwards, he’s forced to do an about-turn with his paper’s editorials and news coverage and make it a propaganda mouthpiece for Windrip and his government, as every other official news outlet in America had become.

Later, a disgusted and horrified Doremus hooks up with a resistance movement, the New Underground, run by a dissident senator called Walt Trowbridge who’s escaped to and based himself in Canada, and he begins surreptitiously writing and distributing an anti-Windrip newsletter called The Vermont Vigilance. Later still, Doremus and his associates are rumbled and they wind up in a concentration camp. But the story isn’t quite over yet for the dogged old editor…

© Penguin Books

As I said earlier, when you read It Can’t Happen Here today, there’s an elephant in the room – a corrupt, authoritarian, orange-skinned elephant, one with a bad combover, a ludicrously long red tie, a big mouth, a small pair of hands, a tiny but cunning brain, a criminal record, and a penchant for cheating at golf. Yes, it’s shocking how much Lewis’s novel anticipates what Trump is up to in America at the moment.

As with Trump and his Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency, which is now better funded than most countries’ armies and is no doubt attracting into its ranks all sorts of far-right nutjobs, Windrip sets up a militia called the Minute Men (MMs) and recruits into it thugs and low-life who relish having the power to intimidate, bully, beat up and murder their neighbors. Doremus’s life gets progressively harder as Shad Ledue – his former handyman, who’s a lazy, ignorant brute and who lusts after his youngest daughter – joins the local Minute Men and, gradually, shins his way up the pole until he becomes District Commissioner. And Trump’s enthusiasm for creating ‘immigration detention facilities’, like the notorious ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ in Florida, mirrors Windrip’s enthusiasm for creating concentration camps, like the one Doremus latterly finds himself an inmate of.

It Can’t Happen Here makes much of the regime’s assault on academia. Early on, Doremus receives a worried letter from an acquaintance at his old alma mater, Isiah College, warning about how its Board of Trustees is bending to Windrip’s malevolent will. “What,” he asks, “can we do with such fast exploding fascism?” Trump has famously tried to do the same with America’s universities – some, like Columbia University, groveling to him pathetically; others, like Harvard, putting up slightly more of a fight.

Windrip sees to it that the ‘most liberal four members of the Supreme Court resigned and were replaced by surprisingly unknown lawyers who called President Windrip by his first name.” Trump, of course, has made sure that the present-day Supreme Court is packed with yes-men and yes-women.

And in an effort to bolster its authority, Windrip’s regime launches an operation to end ‘all crime in America forever’. Criminals are “tried under court-martial procedure; one in ten was shot immediately, four in ten were given prison sentences, three in ten released as innocent… and two in ten taken in the MMs as inspectors.” That sounds suspiciously like Trump’s recent takeover of Washington D.C., supposedly in the name of ridding the capital city’s streets of crime, though more likely to divert attention from the possibility that Trump’s name appears in the US Justice Department’s files investigating Jeffrey Epstein.

Generally, Lewis’s descriptions of how Windrip manages to captivate the American public, or a section of it sufficiently large to get him into power, are depressingly similar to how Trump weaves a spell over his ‘MAGA faithful’ – portraying himself as an outsider and anti-establishment figure, despite the fact he’s the son of a real-estate millionaire and has had everything handed to him on a plate. Of Windrip, Lewis says: “…he was the Common Man twenty-times-magnified by his oratory, so that while the other Commoners could understand his every purpose, which was exactly the same as their own, they saw him towering above them, and they raised their hands to him in worship.”

Meanwhile, Lewis highlights how the regime puts in positions of authority people who are worthless but unswervingly loyal to Windrip. That loyalty, of course, rewards them with wealth, power and prestige. Trump too has populated his government with sycophantic mediocrities, self-serving grifters and dangerous incompetents like Pete Hegseth, Kristi Noem, Robert F. Kennedy Jr, Tulsi Gabbard, Pam Bondi and Marco Rubio. Their single virtue, in Trump’s eyes, is their ceaseless willingness to bow, scrape and debase themselves before him.

There’s even a parallel with Elon Musk who, as the world’s richest man and CEO of the social-media platform X, has a massive ability to inform and misinform people and shape their opinions. The It Can’t Happen Here version of Musk is Bishop Paul Peter Prang, a priest who makes a hugely popular and influential weekly address on the radio. Like Musk’s voice on social media, Prang’s voice ‘circled the world at 186,000 miles a second’ and practically ‘leapt to the farthest stars.’ (Prang’s character was inspired by a real-life demagogue, the ‘Radio Priest’ Charles Coughlin.) And like Musk with Trump, Prang enthusiastically backs Windrip for president – but gets short shrift from the man he’s championed once he’s across the threshold of the White House. Though while Trump merely dropped and humiliated Musk, Windrip sticks Prang in jail and then in an ‘insane asylum’: “No one willing to carry news about him ever saw Bishop Prang again.”

All that said, It Can’t Happen Here is not a perfect book. It has certain features that earn it the dreaded sobriquet ‘of its time’. The focus is almost entirely on a handful of comfortably well-off white Americans and, though there are brief references to the horrors Windrip visits upon the black community, the book shows no interest in exploring these. Also, Lewis makes mocking references to sexuality of Lee Sarason, Windrip’s Machiavellian campaign manager, who wears ‘violet silk pajamas’ and obviously has a fondness for strapping young men. But no mention is made of the regime’s official policy towards homosexuals, which presumably would have been as murderous as Nazi Germany’s. And male chauvinists will appreciate how Doremus gets to have his cake and eat it throughout the book, in that he’s simultaneously married to one woman, dull, frumpy Emma, and engaged in an affair with another, the bewitching firebrand Lorinda. He’s never taken to task for this.

And the book’s tone can be awkward at times. Lewis writes it in a folksy, sardonic, Mark Twain-like style that sometimes works, especially when its poking fun at the general hypocrisies, absurdities and idiocies of Windrip’s regime. It works less well when it’s detailing the brutal realities of that regime – the tortures and humiliations, for instance, that Doremus has to endure while he’s in a concentration camp. For subject-matter as bleak as this, I suspect the only way to record it is with the precise and dispassionate prose of, say, George Orwell’s 1984 (1949).

Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here may not quite make it into the top tier of great dystopian novels, then. However, in 2025, you’re unlikely to read one that feels more terrifyingly prescient.

From wikipedia.org / © Touring Club Italiano