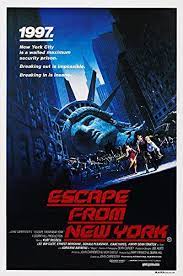

© Brandywine Productions / 20th Century Fox

Brian Glover’s Wikipedia entry begins with a quote from the great man that served both as a mission statement and as a career summary: “You play to your strengths in this game. My strength is as a bald-headed, rough-looking Yorkshireman.” For a quarter-century, Glover played characters that were shiny of pate, pugnacious of visage and flat of vowels in many a British movie, TV show and stage play, and in the process made himself one of the most recognisable character actors in the country.

Born in Sheffield and brought up in Barnsley, the young Glover initially followed in his father’s footsteps. His dad had been a professional wrestler and, while attending the University of Sheffield, Glover topped up his student grant by wrestling too. He fought bouts under the moniker of ‘Leon Aris, the man from Paris’ and was good enough to appear on television, featuring in the Saturday-teatime wrestling slots shown on the ITV programme World of Sport that, a half-century ago, turned such burly, grappling bruisers as Kendo Nagasaki, Giant Haystacks, Mick McManus, Jim Brakes and Big Daddy into household names. He continued to wrestle long after he’d graduated and settled into a respectable day job, which was teaching English and French at Barnsley Grammar School.

One of Glover’s school colleagues was Barry Hines, who’d authored the novel A Kestrel for a Knave. In 1968, this was filmed as Kes by the incomparable Ken Loach. Loach needed someone to play the puffed-up, preposterous and loutish Mr Sugden, the PE teacher at the school attended by Kes’s put-upon, juvenile hero, Billy Casper (Dai Bradley). Hines suggested Glover. For his audition, and to test Glover’s believability as a teacher, Loach staged a playground brawl and got Glover to break it up. This obviously wasn’t difficult for him, being a teacher already and a wrestler.

Glover’s turn as Sugden, who organises a football match with his pupils, insists on captaining one of the teams, and then cheats, dives and brutally fouls the kids while spouting his own match commenatary – likening himself to “the fair-haired, slightly-balding Bobby Charlton” – provides a bleak film with its one shaft of comic sunshine. Come to think of it, Loach’s 1998 movie My Name is Joe has some funny footballing sequences too, and when he finally got round to directing a proper comedy, it was 2009’s Waiting for Eric with French soccer legend Eric Cantona. The beautiful game is clearly the one thing guaranteed to make the famously grim, anti-establishment Loach lighten up.

© Woodfall Film Productions / United Artists

Glover spent another two years teaching before his next acting assignment, which was a role in the Terence Rattigan play Bequest to the Nation. Thereafter, he swiftly became ubiquitous. On television he appeared in Coronation Street (1972), The Regiment (1973), Dixon of Dock Green, The Sweeny, Quiller (all 1975), Secret Army (1977), Minder (1980), Last of the Summer Wine and Doctor Who (both 1985). In that last show he makes a memorable exit when he’s blasted away by some Cybermen. He also gives notable performances in two 1970s shows written by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, who at the time scripted virtually the only British TV sitcoms set outside London and southeast England. In a famous 1973 episode of Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads he plays the devious Flint, who makes a bet with Geordie heroes Bob and Terry that they can’t get through the day in Newcastle-upon-Tyne without hearing the result of an important football match. A year later, Glover joined the cast of Clement and La Frenais’ revered prison sitcom Porridge, playing the hapless, slow-witted convict Cyril Hislop, whose key line is: “I read a book once. Green, it was.”

When not playing bald-headed, rough-looking Yorkshire chancers and convicts, Glover could leaven his northern tones with a twinkly avuncularity, which made him popular among advertisers. Thus, when his face wasn’t popping up on TV shows, his voice was popping up on commercials between TV shows. He voiced the TV advertisements for Allinson’s bread – “Bread with nowt taken out” – and for Tetley teabags. In the Tetley ads, he played the leader of the Tetley Tea-folk, an animated tribe of diminutive, white-coated, cloth-capped characters tasked with the exacting job of giving each teabag its ‘2000 perforations’.

© Wellborn / United Artists

Meanwhile, during the 1970s, Glover became a regular in British movies. These included Lindsay Anderson’s oddball 1973 epic O Lucky Man! and its follow-up, 1982’s Britannia Hospital (about which I intend to write on this blog very soon); Michael Crichton’s 1979 period adventure The First Great Train Robbery; and Terry Gilliam’s 1978 medieval comedy Jabberwocky, in which he plays the foreman of an ironworks that’s reduced to chaos when Michael Palin blunders into it. In Douglas Hickox’s 1975 London-set thriller Brannigan, he’s a minor villain who gets roughed up by John Wayne, playing a tough American cop on an assignment to the British capital – Wayne creates mayhem as he behaves like a Wild West sheriff dealing with an unruly frontier town. “Now,” he warns Glover, “would you like to try for England’s free dental care or answer my question?”

In 1981, John Landis made his much-loved horror-comedy An American Werewolf in London, the opening scenes of which, set in a northern pub called the Slaughtered Lamb, called for a bald-headed, rough-looking Yorkshireman. Obviously, there was only one man for the job. Landis duly cast Glover and the resulting scene, wherein he entertains the Lamb’s patrons with his ‘Remember the Alamo!’ joke, is, along with Kes, his finest cinematic moment – both films show what a fine comic actor he was. Unfortunately, the pub’s jovial mood is then ruined when David Naughton and Griffin Dunn inquire about the strange five-pointed star painted on the wall. And as they’re ejected from the premises, Glover utters the film’s most quoted piece of dialogue: “Beware the moon, lads!”

© PolyGram Pictures / Gruber-Peters Company / Universal Pictures

Three years later, Glover turned up in another classic werewolf movie, playing a villager in Neil Jordan’s adaptation of Angela Carter’s gothic short story, The Company of Wolves. At one point, he’s involved in a brawl with the previous subject of this Cinematic Heroes series of posts, David Warner; and at another, he comes out with a very Yorkshire-esque line: “If you think wolves are big now, you should have seen them when I were a lad!”

Glover faced another monster, a slimy one rather than a hairy one, in 1992’s Alien 3, wherein he plays the warden in charge of a prison-colony on the stormy planet Fiorina 161. Sigourney Weaver crash-lands there, unwittingly bringing with her a cargo of egg-laying alien face-huggers. Directed by a young David Fincher, Alien 3 is a much-maligned film. It can’t help but seem anti-climactic after the previous film in the Alien series, James Cameron’s barnstorming Aliens (1986), and the fact that it begins by killing off most of the characters left alive at the end of Aliens didn’t endear it to fans. It’s got some wonderfully grungy set design, though, and there is something heroic about the film’s un-Hollywood-like, and commercially-suicidal, pessimism. Even Weaver herself gets it at the end.

One of Alien 3’s biggest problems is that, due to incompetent scripting and editing, most of its interesting characters – Glover, Charles Dance, Paul McGann – vanish from the story halfway through. Incidentally, for British audiences, Glover perhaps brought a little too much baggage to his role. When I saw Alien 3 in an Essex cinema, a scene where Weaver confronts Glover in his office, while he – voice of the Tetley Tea-folk – absent-mindedly dunks a teabag in a cup of boiling water, provoked guffaws.

© Brandywine Productions / 20th Century Fox

Glover must have got on well with Sigourney Weaver, for he subsequently turned up in 1997’s Snow White: a Tale of Terror, in which Weaver played the evil queen. Another late role was in the endearingly off-the-wall 1993 comedy Leon the Pig Farmer, in which a young Jewish Londoner, played by Mark Frankel, gets the unsettling news that he was the result of an artificial-insemination mix-up and his father is actually a Yorkshire pig farmer – inevitably a bald-headed, rough-looking one played by Glover. What makes Leon, which also starred Fawlty Towers’ Connie Booth and former Bond girl Maryam D’Abo, slightly melancholic to watch now is the knowledge that lead-actor Frankel died in a motorcycle accident a few years later.

Glover’s stage CV was as busy as his film and TV ones. He appeared with the Royal Shakespeare Company in productions of As You Like It (playing, appropriately, Charles the Wrestler) and Romeo and Juliet, while other theatre work included Don Quixote, The Iceman Cometh, The Long Voyage Home, The Mysteries and Saint Joan. Lindsay Anderson, a stage director as well as a film one, cast him in productions of the David Storey plays The Changing Room and Life Class and Joe Orton’s What the Butler Saw. Such was Glover’s fame by the time he appeared in a West End version of The Canterbury Tales that it was advertised with a slightly amended version of one of his catch-phrases: “Chaucer with nowt taken out.”

Glover was a literary figure as well. He was a prolific playwright and writer, was responsible for over 20 plays and short films, and penned a column in a Yorkshire newspaper. Asked to contribute a script to a 1976 TV drama anthology called Plays for Britain, which also featured writing by Stephen Poliakoff and Roger McGough, Glover found himself short of inspiration. He ended up paying a visit to a police station and inquiring if they’d experienced anything unusual lately that he might be able to use as an idea. While he was at the station, a woman trooped in to the front desk to report indignantly that someone had pinched her front door. Suddenly, Glover knew what his story would be about.

Meanwhile, I remember seeing him on a TV arts programme, discussing – with Anthony Burgess, no less – Paul Theroux’s acerbic 1983 travel book about the British coastline, The Kingdom by the Sea. Glover, who during his wrestling days had toured many of the towns Theroux wrote about, took particular exception to a comment Theroux made about Aberdeen: “…the average Aberdonian is someone who would gladly pick a halfpenny out of a dunghill with his teeth.”

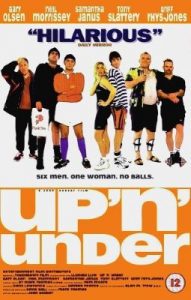

© UK Film Council / Entertainment Film Distributors

Alas, in September 1996, Brian Glover met his own Alamo. He underwent an operation for a brain tumour, although a fortnight later he was back at work, making one of his final films, Up ‘n’ Under. Fittingly, this was about the north-of-England sport of rugby league and was made by the playwright John Godber, whose debut play Bouncers has become a much-revived classic. Glover was among the first people to go and see Bouncers when it premiered at the Edinburgh Festival in 1977 and was quick to offer Godber encouragement. Despite the surgery, the tumour eventually killed him in July 1997.

Thanks to his gruff-but-lovable persona, unmistakable voice, and talent for stealing any scene he was in, Glover lives on in the memory of people like me, who grew up watching a lot of television and movies in 1970s and 1980s Britain. Those folk include actor Jason Isaacs, who admits to using him as inspiration for his star turn as the Soviet war-hero and Red Army commander-in-chief Georgy Zhukov in Armando Iannucci’s historical satire The Death of Stalin (2017). While he played Zhukov as a blunt, abrasive and – crucially – Yorkshire-accented bad-ass, Isaacs said, “I had a picture of Brian Glover in my head. Magnificent actor.”

Meanwhile, Glover is buried in Brompton Cemetery in London, where a simple gravestone describes him as a ‘Wrestler… Actor… Writer’. Not just a Yorkshireman, then, but a true Renaissance man.

From wikipedia.org / © Edwardx