I can’t think of anything festive-related to write about just now, so here’s a travel piece about a charming place I visited a couple of Christmases ago when holidaying in Thailand.

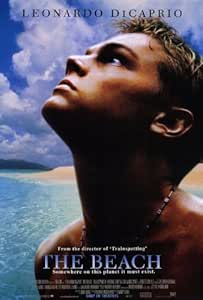

My partner and I visited the village of Koh Panyee while we were staying at the Thai resort of Khao Lak. One day we took a boat tour around Ao Phang Nga National Park, which is actually mostly water – it’s a big, island-strewn bay in the Andaman Sea. Having been to the island of Khao Phing Kan, famously known as ‘James Bond Island’ because it was a location used in the 1974 Bond movie The Man with the Golden Gun, we stopped at Koh Panyee for a late lunch.

As far as I can tell, Koh Panyee is also the name of the island the village adjoins. However, as the majority of that island is a hulking mass of limestone, with vertical, vegetation-choked cliffs, and only a small part of it can be built upon, most of the village juts out over the adjacent sea on a forest of stilts. Centuries ago, it was founded by two families of nomadic Javanese fisherfolk. Now it is home to about 1600 people.

To get to the restaurant where we were dining, our boat travelled the length of the village’s seaward façade. This was an assortment of houses with corrugated iron and tiled roofs, plus a chaotic mantle of wharves and jetties where fishing nets were piled and boxes, crates and lobsters-traps were stacked. Some sections of the mantle were fixed, some were floating, and some had truck or tractor-tyres attached to cushion them against the hulls of berthed boats. The restaurant was a big building, also on stilts, at the end. On one side of its interior was the eating area and on the other side, next to the rest of the village, was a maze of stalls selling souvenirs, fabrics, clothes and jewellery. After I’d had lunch there, I went exploring. I threaded between the restaurant’s stalls, stepped out through a doorway and found myself on a winding, concrete-surfaced walkway that led into the heart of Koh Panyee.

In fact, there were many more souvenir stalls along the sides of that walkway. Though fishing is its biggest money-spinner, tourism is still important in the village, at least, during the dry season. But the local vendors didn’t try to push their wares on me aggressively. And seeing the village itself was fascinating.

The most striking thing was when I looked between the houses on either side, half-expecting to see alleyways, and found there weren’t any. There were just gaps with strips of mossy-green seawater at their bottoms, glinting in whatever sunlight managed to penetrate between the eaves. The edges of the concrete walkway really were edges, with nothing solid beyond them. Often, the edges were blocked off by rows of potted plants, by blue plastic barrels, or by racks of drying fish. Wooden ladders sometimes descended from them to the water, where boxes and buckets rested on and small boats were tethered to platforms – stationary ones, rigged out of planks and poles, or floating ones, weighed down and stabilised against the swell by lumps of concrete.

I noticed a few young kids wandering about that walkway. If I’d been a parent there, I’d have worried about them toppling over one of the edges and into the sea. But no doubt they’d been trained to stay safe. (I should say I spent my childhood in a risky environment myself. Two roads formed a junction a couple of yards from my front door, immediately past that junction was a river, and at my back door rose a flight of steep, high concrete steps that didn’t have railings. Yet my parents instilled enough common sense in me to avoid death by car accident, drowning or falling.)

For some reason, a ricketty-looking bicycle was stowed on a narrow shelf, two planks wide, above the water at the side of one house. Elsewhere, there were birds in box-shaped cages hanging from beams between the houses, and any space on a ledge or doorstep seemed to be tenanted by a dozing cat. Indeed, one shop window sported a sign with the warning, BEWARE OF THE CAT.

The inhabitants of Koh Panyee are Muslims. The three golden orbs of its mosque – its dome and the finials at the tops of its minarets – can be seen from the sea, hovering above the clutter of rooftops. Approaching the mosque area, I encountered a sign cautioning me about what was not permitted ahead: no alcohol, drugs, bikinis, dogs or pigs, and I shouldn’t litter, be noisy or ‘buy and sell’. The mosque stands on a shelf of solid ground at the foot of the island’s limestone cliffs, opposite the entrance of a Muslim cemetery. On my way there, I passed through a transitional region where below the houses there was neither water nor solid ground, but dark, treacly mud. Presumably, that mud would be underwater at high tide.

Considering its location, one of the very last things you’d expect to win fame for Koh Panyee is its inhabitants’ prowess at football. Yet according to its Wikipedia entry: “The village includes a floating football pitch. Inspired by the 1986 FIFA World Cup, children built the pitch from old scraps of wood and fishing rafts. The boys decided to form a football team and compete in the Southern Thai School Championships. After making it to the semi-finals in an inland tournament… all of the village was inspired to take up the sport… As of 2011, Panyee FC is one of the most successful youth soccer clubs in southern Thailand.”

And it seems that the people of this aquatic village are Liverpool fans. Yes, they support the Reds. Just past the sign for the mosque, I discovered evidence of where their footballing loyalties lay – a colourful wall display emblazoned with slogans such as RED MACHINE and YOU’LL NEVER WALK ALONE, with the Liverpool FC crest, and with a portrait of Mo Salah. Indeed, I’ve read that legendary former Liverpool player John Arne Riise visited the village in 2019.