A while back, my partner and I decided to tackle one of the to-do things on our Singaporean bucket-list and paid a visit to the city’s celebrated Gardens by the Bay.

Every day I get to view the Gardens, or at least the two huge domes that dominate them. They’re visible from the bridge over Marina Bay that my bus crosses when I’m travelling to and from work. With their exoskeletons of giant, curved ribs, the domes resemble a pair of gargantuan woodlice huddling in the vegetation not far from the Marina Bay Sands building (which is distinctive in appearance too – like a huge, futuristic version of one of the structures of standing stones and lintel stones at Stonehenge).

We entered the taller dome first. It contains what’s known as the ‘Cloud Forest’ and, to quote the Gardens’ website, is “home to one of the world’s tallest indoor waterfalls and a lush mountain clad with plants from around the world.” Our visit coincided with the dome hosting a temporary display called Avatar: The Experience. For the most part, this meant that life-sized fibreglass representations of the Na’vi and other examples of the flora and fauna of Pandora, the planet featured in the James Cameron movies Avatar (2009) and Avatar: The Way of Water (2013), were positioned among the vegetation inside, allowing fans of the movies to pretend they were seeing them in the movies’ alien jungle. Even if I’d been an Avatar enthusiast, which I’m not – I thought the first one was merely okay and I haven’t seen the second one – I would have found these annoying. Their presence was a distraction from the works of ethnic / indigenous art, from such places as East Timor and Malaysia, that stand permanently amid the foliage. Still, it wasn’t too difficult to ignore the Avatar paraphernalia, even if a lot of people – especially young kids – clustered around them taking selfies.

The dome’s main feature is a hulking, sandcastle-shaped mountain covered in a shaggy cloak of ferns, leaves, fronds, creepers, briars and occasional flowers. However, like the volcano in the James Bond film You Only Live Twice (1967), the mountain isn’t what it first appears. It’s not the secret HQ of a supervillain planning world domination, but behind the greenery festooning its exterior, it’s a structure of decks, terraces, lift-shafts and staircases. Not only can you go up inside the mountain and look out from its various levels, but you can follow elevated catwalks that swirl away from it, past the tops of the surrounding trees, to the internal surface of the dome itself.

When we came through the entrance doors, we were struck by a chilly mixture of water droplets and water vapour emanating from the bottom of the waterfall mentioned on the website – really, five streams of water pouring down from five spouts near the mountain’s summit. The water hits the ground near a Māori sculpture, made out of totora wood, slightly reminiscent of a Japanese torii, and unveiled there by Jacinda Ahern during a visit in 2022. Thereafter, you need a couple of minutes to get accustomed to the organisation of the place. To your right, the path takes you around the base of the artificial mountain. Above you, the catwalks encircle the mountain like hula-hoops swinging around a burly torso. And above and beyond everything else, the dome’s glass extends in a massive, curved grid of steel. At the time, three cleaners in abseiling-like harnesses were working their way down the outside of the dome, scrubbing it with long-handled brushes, sluicing it with jets of water, and looking absolutely tiny.

A lift took us to the mountain’s top. From there, you gradually descend, enjoying the different levels’ views and wandering along the catwalks as they loop out and back again. Amid the botanical displays at the very top is one containing pitcher plants, bladderworts, butterworts, sundews and Venus flytraps – yes, it’s a collection of carnivorous plants. The Venus flytraps are contained in a couple of glass globes suspended above the display, their fanged maws sprouting from masses of soil and plant-matter. This was the first time I’d seen the famously fly-hungry plant for real and I was surprised by how small it was. Despite its diminutive size, it still looked sinister, like a vicious, vampiric little Pac-Man.

Obviously, we took advantage of the catwalks. These lead you away from the mountain, past the treetops, and right to the dome’s inside surface, where you can peer out through the last leaves and stems at such Singaporean landmarks as the aforementioned Marina Bay Sands building or the Singapore Flyer, the observation wheel that looms over the Formula One track. It feels like being an explorer who’s just set eyes on the great, lost city of Singapore from the edge of a giant jungle-clearing.

Beneath the mountain, on a basement level, there’s an area known as the Secret Garden. Threads of water leak down from the complex above, into what seems a congested and chaotic muddle of ferns, shrubs, branches, vines and flowers – though this being Singapore, it’s no doubt highly structured and organised in reality. One reason why I liked the Secret Garden was because of its collection of sculptures, made from gnarly and sprawling segments of tree-trunk, tree-branches and tree-roots. Not only have these been trimmed, smoothed and varnished, but among them lurk cunningly-hidden, carved animals. Thus, a zig-zagging chunk of tree-trunk that serves as a garden-bench has, skulking along its surface, a crocodile’s head; while a twisting, tangled section of treetop, erected like a statue, is home to a wolf reposing along one of its branches.

The dome’s temperature is controlled and kept to an agreeably cool level. It made a pleasant change to be able to walk amid nature in Singapore for an hour and not end up drenched in sweat.

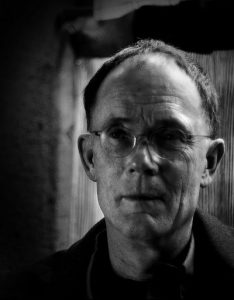

As I said, the Avatar exhibits (which also included cubicles in the basement-area where you could get your photo taken and have it superimposed on a Pandoran landscape, and an animatronic dragon-creature that threateningly stirred and crankily growled), didn’t impose too much on our Cloud Forest experience. The biggest imposition was probably when we found ourselves sharing a lift with an incredibly excited wee boy, who was enthusing to his mother about how wonderful the dome was because it was so full of Avatar stuff. Then he became aware of my surly, bearded presence behind him, turned around, looked up at me, and declared, “I love you, Mr Klingon,” before kissing my belt-buckle. Well, that was unexpected. Though if I had to be mistaken for an alien species, I would far rather it was a grumpy warrior race who dress like they’re in a 1980s heavy metal band and say cool things like, “Surrender or die!”, rather than a wimpy bunch of blue-skinned James Cameron-ian space-hippies like the Na’vi.

Then we headed for the other dome at Gardens by the Bay, the Flower Dome. But that’s a topic for another blog-post.