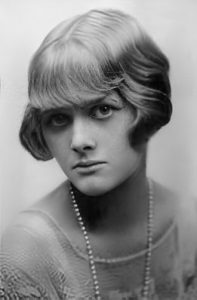

From instagram.com / Roger Corman

Roger Corman, who passed away on May 9th at the venerable age of 98, wasn’t so much a filmmaker as a movie factory. IMDb credits him with 491 producing credits, and that’s not counting the two movies being produced by him and categorised as ‘upcoming’ at the time of his death: the generic-sounding Crime City and the definitely Cormanesque-sounding Little Shop of Halloween Horrors.

Even during lockdown in 2020, when most folk his age were lying low because they knew contracting Covid-19 was likely a death sentence for them, Corman was so desperate for something celluloid-related to do that, according to the Hollywood Reporter, he “launched a self-named Quarantine Film Festival to judge short films made while filmmakers shelter in their homes.”

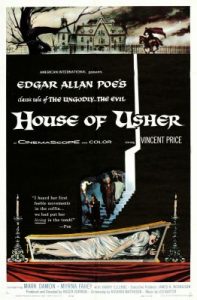

Corman was famous for things besides his work ethic and prolificness. Firstly, there was the legendary thrift and speed with which he made his films. For instance, in his 1955 Western Apache Woman, actor Dick Miller – at the start of a long association with Corman – played two characters in the same scene, an Apache and the settler who shoots him. While figuring out how to film the fiery – and potentially costly – finale of 1960’s House of Usher, Corman heard there was a barn about to be demolished in Orange County. He got permission to do the demolition himself, burned it to the ground, had cameramen film it and used the burning-barn footage to represent the burning mansion at the movie’s climax. And the original 1960 Little Shop of Horrors, long before it became an Alan Menken musical and was remade by Hollywood in 1986, was shot in two days. Supposedly, Corman did it in response to a bet that he couldn’t make a film in two days.

© Alta Vista Productions / American International Pictures

Secondly, as a producer, he gave a lot of aspiring, up-and-coming talent a chance to get behind or in front of the camera and show the world what they could do, whilst learning the mechanics of filmmaking on the job. The young filmmakers who graduated from the Corman School of Moviemaking make a pretty awesome list: Peter Bogdanovich, James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola, Joe Dante, Jonathan Demme, Carl Franklin, Curtis Hanson, Monte Hellman, Ron Howard, Gale Anne Hurd, Jonathan Kaplan, John Sayles and Robert Towne. A few others, like Paul Bartel and Jack Hill, never quite escaped the ‘exploitation filmmaker’ tag, but made some fascinating movies nonetheless, while Allan Arkush became a prestigious, Emmy-nominated TV director. Meanwhile actors whose careers received invaluable leg-ups from Corman included Charles Bronson, Bruce Dern, David Carradine, Peter Fonda, Pam Grier, Robert De Niro, Dennis Hopper, Tommy Lee Jones, Jack Nicholson, Talia Shire and, yup, Sylvester Stallone. Even Sandra Bullock was aided on her way to fame by a role in the 1993 Corman-produced jungle-epic Fire on the Amazon.

I’m sure this was due to economics as much as altruism. He could pay his young, unknown and inexperienced directors, writers, actors and technicians less. When Ron Howard worked for him, and they had a row about Corman’s stinginess, Howard was assured: “Ron, if you do a good job for me on this picture, you’ll never have to work for me again.” (And no doubt he’d have a chance of being remembered not just for playing Richie Cunningham in the 1974-84 sitcom Happy Days.) But the lessons Corman’s alumni learned about making films on tight budgets and schedules were invaluable for their later, more prestigious careers and they’ve generally been grateful for the breaks he gave them. Scorsese, for example, has spoken about how Corman taught him the importance of preparation when you’re shooting on a budget and the wisdom of getting the most difficult scenes filmed at the start of the schedule – which in Scorsese’s case, with the 1972 Corman-produced gangster movie Boxcar Bertha, were the ones involving a train.

© American International Pictures

The fuss made over Corman’s many protegees obscures an important fact, that as a director himself – he had 56 directing credits – he could be pretty good. The movies he directed can be divided into three phases. First came the ultra-low-budget ones, mostly Westerns and science-fiction flicks, that he churned out in the late 1950s. If you’re to believe IMDb, he managed to make nine of these in 1957 alone. Many you’d struggle to appraise as ‘good’… But when you compare them with the cheap schlock being made by other exploitation filmmakers at the time, they definitely have a spark that elevates them above the herd. One thing about late-1950s, micro-budget, black-and-white sci-fi movies that strikes you now when you view them on YouTube is how dreary most of them seem – but dreariness isn’t a charge you could level at, say, Corman’s It Conquered the World (1956), though you could level a lot else at it.

At the beginning of the 1960s, he convinced his regular studio, American International Pictures, to tackle something different: a series of films based on the works of Edgar Allan Poe, made in colour and with larger budgets than usual (which doesn’t mean their budgets were large by anyone else’s standards). These kicked off in 1960 with House of Usher and continued with The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), The Premature Burial (1962), Tales of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), The Haunted Palace (1963) – actually based on an H.P. Lovecraft story, with the title borrowed from a Poe poem – The Masque of the Red Death (1964) and Tomb of Ligeia (1964). All but one feature the impeccable horror-icon Vincent Price as their leading man and they’re enlivened too by appearances from an older generation of horror-film actors: Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney Jr, Peter Lorre and Basil Rathbone. And let’s not forget Barbara Steele, the queen of 1960s Italian horror cinema, who pops up in Pit. Corman’s Poe films are atmospheric, brooding – several of them have Price mourning a dead (but actually not-so-dead) wife – at times gorgeous and generally a lot of fun. They had a big impact on peculiar children like me, who caught them on late-night TV in the 1970s.

© Alta Vista Productions / American International Pictures

Finally, in the late 1960s, Corman became involved in movies about the youth cultures of time – Hells Angels in The Wild Angels (1966) and hippiedom in 1967’s The Trip – and gangster films like The St Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967) and Bloody Mama (1970), possibly inspired by the success of a wee film called Bonnie and Clyde (1967) around the same time. Worn out by directing, Corman concentrated on producing from the early 1970s onwards. Apart from some uncredited directing on 1978’s Deathsport and 1980’s Battle Beyond the Stars, he returned to the director’s chair only once, in 1990, for an adaptation of Brian Aldiss’s novel Frankenstein Unbound (1973). Aldiss also wrote the short story Supertoys Last All Summer Long (1969) which was developed into Steven Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001), making him perhaps the only writer who could boast of having his work filmed by both the famously low-budget Corman and the famously high-budget Spielberg.

Thereafter, Corman formed a series of movie production and distribution companies – New World Productions, Millennium (which was quickly renamed New Horizons Pictures) and Concorde Pictures. Going through all the movies that came off their conveyor belts, and had Corman’s name in their ‘producer’ credits, would be an exhausting and probably impossible task. But there are certain ones I’m fond of.

© New World Pictures

Firstly, I like Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (1975), about a futuristic car race where the goal is not to finish first but to rack up as many points as possible by running down as many pedestrians as possible. A young Sylvester Stallone plays the villain, a driver so evil he mows down his own road crew for some extra points. Bartel followed this with another movie about car chases and car crashes, the more family-friendly Carquake (1976). I loved this as a kid – the fact that I saw it on a double bill with The Giant Spider Invasion (1976) probably made it seem, comparatively, so good. Among its oddball pleasures are cameos by Stallone and Martin Scorsese playing a pair of KFC-chomping Mafiosi.

I’m also a fan of Joe Dante’s Piranha (1978) and Rock n’ Roll High School (1979) directed by Allan Arkush with some contributions from Dante. The latter film starred the excellent P.J. Soles, shortly after she’d appeared in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), and the legendary punk-rock band the Ramones. Apparently, Corman had wanted the movie to be about disco music, until Arkush and Dante persuaded him that having the Ramones in it was more likely to piss off the teenaged audience’s parents.

© New World Pictures

I enjoyed Corman’s 1980 rip-off of Star Wars (1978), the aforementioned Battle Beyond the Stars, ostensibly directed by Jimmy T. Murakami (and co-written by John Sayles). Its crew included a young James Cameron, working as a modelmaker, special effects technician and art director. Supposedly, Cameron impressed Corman by designing for the film a spaceship called Nell (controlled by a female-voiced computer) whose twin engines were, frankly, shaped like breasts. Cameron also worked on Bruce D. Clark’s Galaxy of Terror (1981), a cash-in on Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), which I like simply for its eclectic cast – Ray Walston; Sid Haig; Zalman King, future director of ‘erotic’ movies like Wild Orchid (1990) and Delta of Venus (1994); Grace Zabriskie, who played Sarah Palmer in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (1990-91, 2017); Erin Moran, who played Ron Howard’s little sister in Happy Days; and Freddy Kreuger himself, Robert Englund.

And I’m somewhat fascinated – I don’t know why – by Adam Simon’s Carnosaur (1993), which was based on Harry Adam Knight’s 1984 novel of the same name. Knight’s Carnosaur had featured the idea of cloned dinosaurs running amok in the modern world years before Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park (1990). When it was announced that Steven Spielberg would turn Crichton’s book into a film, Corman cannily adapted Knight’s book to the screen and released it the same year as Spielberg’s blockbuster. I imagine Knight found it galling that while Spielberg filmed Crichton’s novel with state-of-the-art animatronic and computer-generated effects, Corman’s low-budget effects for Carnosaur involved a man wearing a dinosaur-suit. Also, cheekily, Corman cast Diane Ladd (who’d been in The Wild Angels) in Carnosaur while her daughter Laura Dern was starring in Jurassic Park.

Later, more giant monsters would feature in Corman’s association with the Syfy channel. He supplied it with a succession of less-than-epic, self-explanatorily titled monster movies like Dinocroc (2004), Supergator (2007), the inevitable Dinocroc vs Supergator (2010), Dinoshark (2010), Sharktopus (2010) and Piranhaconda (2012). Actually, as Wikipedia notes, “Supergator was turned down by the Syfy channel, but Corman made it anyway.” I’ve watched a couple of these on Britain’s Horror Channel and, well, what can I say? There are probably worse ways to reduce your brain to an inert, insentient pulp. But not many.

However, my favourite films among Corman’s output are definitely ones that he directed himself. I’ll talk about them in my next blog post. Stay tuned…

© American International Pictures