From facebook.com

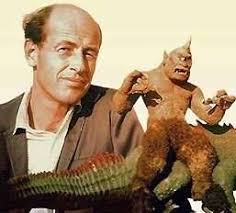

I’ve just discovered that today would have been the 100th birthday of filmmaking and special effects titan Ray Harryhausen. Without the presence of Harryhausen’s movies in my childhood, I suspect I would have developed into a very different, though possibly much more normal, human being. Anyway, to mark the great man’s centenary, here’s what I wrote about him on the sad occasion of his death, back in March 2013.

This week saw the passing of the movie special-effects veteran Ray Harryhausen. Younger filmmakers have been swift to pay tribute to Harryhausen, as they should do – the likes of Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, James Cameron, Peter Jackson, Guillermo del Toro, Sam Raimi, Tim Burton, Nick Park and Terry Gilliam owe him a huge debt in terms of inspiration.

Ray Harryhausen wasn’t just a special-effects technician – he was a special-effects titan, a man who turned the process of stop-motion animation into an art-form and became arguably the greatest backroom wizard in cinematic history. Harryhausen discovered his vocation when, as a kid in 1933, he was taken to a screening of King Kong. Obsessed with the movie, the young Harryhausen learned how the special-effects man and stop-motion pioneer Willis O’Brien had used small, intricately-jointed models of Kong to bring the ape to life. Slowly, methodically, incredibly painstakingly, O’Brien made slight adjustments to those models in between shooting them one frame of film at a time. The result of these countless tiny adjustments was that when the footage was played back you had Kong moving onscreen with life-like fluidity.

Harryhausen was soon making his own stop-motion models and eventually he became apprenticed to O’Brien. Before they won an Oscar for 1949’s Mighty Joe Young – a sort of King Kong-lite, about a giant gorilla who instead of swatting biplanes at the top of the Empire State Building rescues children from burning orphanages – O’Brien advised Harryhausen to work on giving his creations characters, not just mechanical movement. He even suggested that the the budding animator go and study anatomy.

Harryhausen took O’Brien’s advice and he strove to invest his animated figures with soul. As a consequence, in this modern era of CGI-drenched fantasy movies, critics commonly complain that today’s computer-generated monsters ‘lack the personality’ of Harryhausen’s creatures. At the news of Harryhausen’s death, the author and critic Kim Newman tweeted: “It now takes 500 pixel-wranglers to do what Ray Harryhausen did better singled-handed.”

My childhood and adolescence in the 1970s and early 1980s coincided with the final decade of Harryhausen’s film-work – Golden Voyage of Sinbad appeared in cinemas in 1973, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger in 1977 and Clash of the Titans in 1981. Such was the success of Golden Voyage of Sinbad that his original Sinbad movie, 1958’s Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, was subsequently re-released, so I saw that on a big screen too. Meanwhile, Harryhausen’s earlier movies from the 1950s and 1960s, such as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1952), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), Twenty Million Miles to Earth (1957), The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1959), Jason and the Argonauts (1963), The First Men in the Moon (1964), One Million Years BC (1966) and The Valley of Gwangi (1969), had become fixtures on TV.

For some annoying reason, ITV insisted on showing many of these films on weekday afternoons, so that they started while kids like myself were still at school. I remember on one occasion I lied to my teacher so that I could get out of school early, run back to my house and catch the beginning of Jason and the Argonauts at half-past-two.

Though I liked monster movies, I quickly became critical of how their special effects were done. I hated films where the giant creatures were clearly men in suits, stomping on model cities composed of shoebox-sized buildings, as was the case with the Japanese Godzilla movies. I was also unimpressed by dinosaurs that were glove-puppets (see 1974’s The Land that Time Forgot) or magnified real-life lizards (as in 1960’s dreadful remake of The Lost World – “It’s a mighty tyrannosaurus!” cast-members would cry at the sight of something that was obviously a blown-up iguana with additional warts and frills glued onto it.)

But Harryhausen’s creatures were different. Their shapes were uniquely monstrous, so that they couldn’t have special-effects men operating them from the inside, and they moved with a strange, graceful autonomy. Furthermore, his dinosaurs were recognisable dinosaurs – brontosaurs, allosaurs, triceratopses – which was important when you were ten years old.

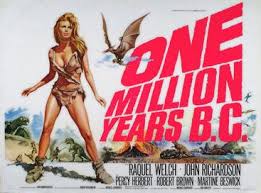

The movies were sometimes less-than-great in other departments. Most notoriously, One Million Years BC, which Harryhausen made for Hammer Films, wasn’t scripted with much attention to paleontological science. It had Raquel Welch and other Playboy Bunny-like cavewomen in fur bikinis living alongside dinosaurs in the Calabrian Stage of the Pleistocene Epoch. Nonetheless, Harryhausen’s work elevated such films into the realms of low art.

© Hammer Films / Seven Arts

Harryhausen came to Edinburgh a dozen years ago and gave a talk at the (now closed) Lumiere Cinema at the back of the National Museum of Scotland. Recently, a literary magazine called the Eildon Tree had published a story of mine that was about growing up in a small town in the 1970s and being dependent on the local fleapit cinema for escape into more exciting and more glamorous worlds. Because of the story’s theme and setting, Harryhausen’s Sinbad movies got mentioned in it a few times. So not only did I attend Harryhausen’s talk, but I brought along a copy of the magazine in case he was doing a signing session afterwards.

Although he was over 80 years old by then, Harryhausen was sharp-witted and good-humoured and he remained in good form despite some stupid questions from the audience. (“Why didn’t you make a movie about the Loch Ness Monster?”) The next day, Peter Jackson was flying him to New Zealand so that he could visit the set of the first Lord of the Rings movie, which was maybe why he was so jovial. There were a lot of kids present and they were entranced by the jointed monster-models from various films that he’d brought with him.

Afterwards, a long queue of people assembled before Harryhausen’s podium with movie memorabilia for him to sign. He observed drily that much of that memorabilia consisted of posters for One Million Years BC, in which Raquel Welch was displayed prominently in her fur bikini – so much for stop-motion animation. Finally, it was my turn. I handed over my copy of the Eildon Tree, open at the page where my story started, and asked if he could autograph it.

“It’s something I’ve had published,” I explained. “It name-checks your Sinbad movies.”

Harryhausen looked at me, chuckled and said, “You know, son, you look a bit like Sinbad yourself!”

That didn’t just make my day – it made my month.

Anyway, to finish, here are my five all-time-favourite Ray Harryhausen monsters.

© Morningside Productions / Columbia Pictures

The Cyclops in Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958)

With its single eye, horn, squashed nose and fang-filled maw, the Cyclops in Harryhausen’s original Sinbad movie was a Satanic-looking thing. During the scene where he lashed one of Sinbad’s crew to a spit and started to roast him over a fire, I seem to remember him licking his lips with hungry anticipation. So evil did the Cyclops seem, in fact, that my ten-year-old self was quite pleased when Sinbad (Kerwin Matthews) finally thrust a flaming torch into his eye and blinded him, and then the bastard plunged over a cliff edge to his death.

© Morningside Productions / Columbia Pictures

Talos in Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

Everybody raves about the fight with the skeletons at this film’s climax, which is indeed spectacular. But it’s the earlier episode on the Isle of Bronze where the massive statue of Talos comes to life and goes lumbering after the crew of the Argo that’s my favourite part of the film. In particular, the moment where Talos awakens is wonderful. Hercules stands with the supposedly lifeless and inanimate Talos looming high in the background – but suddenly Talos’s head creaks around to look at him. It’s the stuff that childhood nightmares are made of. But I mean that in a good way.

© Morningside Productions / Warner Bros – Seven Arts

Gwangi in The Valley of Gwangi (1969)

“Not as good as The Valley of Gwangi,” was my disappointed reaction after watching Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park in 1993. The earlier film, which has cowboys discovering a lost valley in Mexico where prehistoric life has somehow survived to the present day, was originally an unrealised project by Harryhausen’s mentor Willis O’Brien. The scene where the cowboys, on horseback, manage to lasso an allosaurus — the Gwangi of the title — is a brilliant cinematic moment that’s been stuck in my head ever since.

© Morningside Productions / Columbia Pictures

Kali in Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973)

The second of the Sinbad movies has John Philip Law in the title role. He’s up against a villainous sorcerer, played by Tom Baker, who was subsequently picked to play Doctor Who on the strength of his performance here. Baker’s villain, like Harryhausen himself, specialises in bringing inanimate objects to life. In the film’s best scene, he animates a statue of the many-armed Hindu Goddess Kali, equips her with half-a-dozen swords and sends her into battle with Sinbad and his men like a giant, whirling lawnmower of death.

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / United Artists

Medusa in Clash of the Titans (1981)

Clash of the Titans was Harryhausen’s final film and also one of his most underrated. Indeed, I’ve read that the hostile reviews given to Clash were one reason why he decided to retire at this time. (“An unbearable bore of a film,” bitched Variety, “that will probably put to sleep the few adults stuck taking the kids to it.”) Actually, in the years since, it’s become one of his best-remembered pictures and a little while ago it was remade, though inevitably with loads of crap CGI. Its highlight is the scene where Perseus blunders into Medusa’s darkened lair, which is grotesquely populated by the figures of her turned-to-stone victims, and tries to outwit the serpent-haired, serpent-tailed and asthmatic-sounding monster. And with that memorably scary sequence, the great Ray Harryhausen bowed out of film-making.