© Rank Organisation

This weekend saw the funeral of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, who passed away on April 9th at the age of 99. Anyone who’s read the political entries I’ve put on this blog won’t be surprised to hear that I’m not a monarchist, at least as far as Britain is concerned. I’ve got nothing against the Queen, who seems boundlessly dutiful and decent as she pushes her 95th birthday. I’ve even got nothing against the concept of a monarchy itself, if it means having a symbolic head-of-state who deals with all the ceremonial stuff like opening supermarkets and attending banquets while the government gets on with the actual business of running the country. Elsewhere in Europe, small-scale monarchies like this seem to work perfectly well in the Low countries and Scandinavia.

Unfortunately, I don’t think a country as dysfunctional as Britain, so neurotically obsessed with its past, and where the institution seems to bring out the worst in many people – obsequiousness, snobbery, jingoism, culture-warring and my-patriotism’s-bigger-than-your-patriotism flag-shagging – could cope with having a small-scale monarchy. So I think in the long run it would be better for Britain to just dispense with the monarchy and become a republic.

Anyway, enough of the political talk. This seems an opportune time to repost this tribute I once wrote about one of Prince Philip’s close friends – the gruff, pompous acting marvel James Robertson Justice, whom the late prince once described as “a large man with a personality to match” who “lived every bit of his life to the full and richly deserves the title ‘eccentric’.”

Forgive the pun, but in a brief blog entry it’s impossible to do justice to James Robertson Justice. By the time he embarked on an acting career – his first screen appearance was in the Charles Crichton-directed wartime propaganda movie For Those in Peril (1943), with his first substantial role coming four years later in Peter Ustinov’s comic fantasy Vice Versa – he’d already amassed a professional CV that would put, say, Jack London’s to shame.

In London, he’d worked as a journalist at Reuters (alongside a 20-year-old Ian Fleming). Then he’d upped and gone to Canada, where he’d tried his hand at selling insurance, teaching English at a boys’ school and being a lumberjack and gold-miner. He’d worked his passage back to Britain on a Dutch freighter and during the 1930s served as secretary and manager to the British ice-hockey team. He’d also had a go at being a racing driver, served as a League of Nations policeman and fought for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. In World War II he’d been invalided out of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve because of a shrapnel injury.

On top of his decidedly varied working experiences, James Robertson Justice was a polyglot. According to whom you believe, the number of languages he could speak were four, ten or twenty. He was also a keen birdwatcher and falconer – the latter enthusiasm earning him the friendship of Prince Philip – a raconteur and bon viveur with an eye for the ladies and a penchant for fast and expensive cars, and perhaps most passionately of all, a would-be Scotsman. Although he’d been born in Lewisham in London in 1907, to a Scottish father, Justice told everyone that he’d been born in the shadow of a distillery on the Isle of Skye. People believed this and it was only in 2007 that a biographer, James Hogg, discovered his birth certificate and his non-Scottish origins.

To cement his Scottish credentials, Justice served as rector of Edinburgh University from 1963 to 1966 and in the 1950 general election he ran unsuccessfully as the Labour candidate for the Scottish constituency of North Angus and Mearns. Despite his friendship with the Queen’s husband and his taste for fine living, Justice’s politics were firmly of the left. One of the languages he could speak was Scottish Gaelic. And he must have been proud that he starred in the most charming of old Scottish comedy movies, 1949’s Whisky Galore.

© Rank Organisation

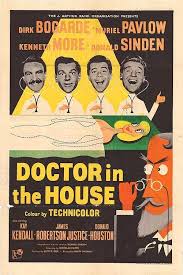

A larger-than-life character in reality, it’s unsurprising that fame, when it arrived for Justice, was a result of him playing a larger-than-life movie role. 1954’s Doctor in the House, based on the comic novel by Richard Gordon, follows the mishaps of four medical students (Kenneth More, Donald Sinden, Donald Houston and soon-to-be-a-star Dirk Bogarde) while they bumble, philander and idle their way through their studies at the fictional St Swithin’s Hospital. Its irreverent tone struck a chord with British cinema audiences, whose patronage made it the biggest grossing film of the year. That’s ‘irreverent’ in strictly a 1954 sense, however. Bogarde and co seem a pretty mild bunch of rebels even by the standards of the 1950s, which a couple of years later would see the advent of rock ‘n’ roll. And as biting and unruly medical satire goes, Doctor in the House isn’t exactly on par with, for instance, Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H* (1970).

In fact, the film would seem flat and stodgy today if it wasn’t for Justice’s turn as the chief surgeon at St Swithin’s, the hulking, pompous and delightfully ogre-ish Sir Lancelot Spratt. The scenes involving Spratt are still capable of prompting guffaws – particularly the one with the famous ‘What’s the bleeding time?’ joke.

Steamrollering through the hospital wards and corridors and dragging a dazed trail of matrons, nurses and junior doctors in his wake, treating his underlings like dirt and so disdainful of the working-class patients that it’s debatable whether or not he considers them capable of thought, Spratt could be seen as the socialist-leaning Justice’s piss-take of a pompous upper-crust Tory doctor, one who’s been thrust against his wishes into the brave new Labourite world of Britain’s fledgling National Health Service. The truth is simpler, though. Justice was simply playing himself, or at least the side of himself who liked fancy cars, caviar and royalty.

The success of Doctor in the House and the popularity of Spratt meant that he was immediately typecast. He’d spend the remainder of the 1950s, and the 1960s, playing variations on the role – comically-blustering aristocrats and authority figures who believed themselves entitled to behave any way they pleased and who didn’t give a tinker’s cuss what other people thought about it.

One exception to the rule was the memorable John Huston-directed, Ray Bradbury-scripted film version of Moby Dick in 1956, in which he played Captain Boomer. Also, in the 1961 adaptation of Alistair MacLean’s The Guns of Navarone, he played the commodore at Allied Command who rounds up Gregory Peck, David Niven and the gang and sends them off to blow up the big German guns of the title. Otherwise, comedies and pomposity were the order of the day. Justice played Spratt in six more Doctor movies, where the quality inevitably went down each time, and played many more Spratt clones. His performances, however, were never less than hugely entertaining.

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

One of my favourites is his turn as the unbearably bear-ish aristocrat Luther Ackenthorpe in 1961’s Murder, She Said, an adaptation of Agatha Christie’s 4.50 from Paddington, which starred the venerable Margaret Rutherford as Miss Marple. The lady detective takes on a job as a maid in the Ackenthorpe household in order to investigate a possible murder, and predictably she and Justice spend the film getting on each other’s nerves. Miss Marple receives a shock at the end because Justice, despite the antagonism that’s existed between them, has concluded that she’s just the woman to share his matrimonial bed. His proposal of marriage hardly sweeps her off her feet, though. “You’re a fair cook,” he tells her, “and you seem to have your wits about you and, well, I’ve decided to marry you.” Unsurprisingly, Miss Marple manages to turn down his proposal without much soul-searching.

Justice is also good in the 1962 comedy The Fast Lady. It has a great cast – Julie Christie, making only her second film appearance, the suave Leslie Philips and the legendary Glaswegian comic performer Stanley Baxter. Mind you, when I saw part of it on YouTube recently I found its humour a lot less sophisticated than how I remembered it from multiple TV viewings when I was a kid. Justice plays a rich and arrogant sports-car enthusiast, a role that was obviously no leap for him, who runs gormless cyclist Baxter off the road. When Baxter tracks Justice down to his country manor to complain, he falls in love with Justice’s daughter, Christie, while Robertson, chugging around on a riding lawnmower, mangles Baxter’s bicycle into his lawn. There follows a romantic comedy of manners, with Baxter trying to win Christie’s hand and earn her father’s respect. I remembering seeing an interview with Baxter wherein he reminisced about the film and, adding yet another string to Justice’s bow, recalled how his co-star had been an authority on butterflies.

Shortly after playing yet another cantankerous and wealthy old bugger, Lord Scrumptious, in 1968’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang – based on the children’s book by his old Reuter’s colleague Ian Fleming – Justice suffered the first of several strokes that would hobble and then finish his film career. By the time of the last Doctor film, 1970’s Doctor in Trouble, his appearance as Sir Lancelot Spratt had been reduced to a cameo. His final role was an appropriately Scottish-themed one, 1971’s The Massacre of Glencoe. As the work petered out, so did his money, and in 1975 he died a sick and bankrupt man. All in all, it was a sad and undignified end for one of the British cinema’s most flamboyant and gloriously imperious figures.