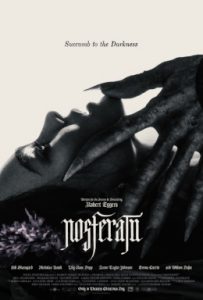

© Focus Features / Universal Pictures

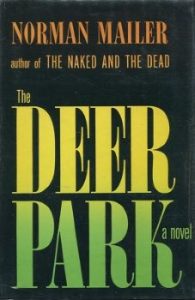

Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu (2024) has finally reached Singapore and a few days ago I watched it in the city-state’s excellent arthouse cinema The Projector. This is Eggers’ reimagining of the 1922 silent horror-movie classic Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, which was directed by F.W. Murnau and based surreptitiously on Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula – though not so surreptitiously that Murnau and his producers escaped being sued by Stoker’s widow for breach of copyright.

The new Nosferatu has provoked some extreme responses. The reaction has been as polarised as the weird relationship at the film’s core, wherein the beautiful, fragrant Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) gets intimate with the gaunt, rotting, pustuled Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), the dreaded nosferatu – vampire – of the title. A while back, I read a very positive review of it by Wendy Ide in the Guardian but was taken aback by the negativity of the some of the comments below the line: “A turd…” “Just awful…” “Absolutely terrible…” “Beyond boring, absolute crap…”

Well, I lean towards the Wendy Ide end of the Nosferatu debate because I thought the film was great. At least, I thought so during the two hours and 12 minutes I sat before it in The Projector. When my critical faculties started to function again – they’d been in a daze during the film itself – I became aware of a few flaws. But generally, thanks to its atmosphere, its visuals, its sumptuous (if drained) palette and its overall craftsmanship, I found it the most impressive version of Stoker’s novel I’ve seen. And yes, though it retains the original Nosferatu’s German setting and German character-names, this is essentially another retelling of Dracula.

Not that I’m saying it’s my favourite version of Dracula. That accolade belongs to the 1958 Dracula made by Hammer Films, directed by Terence Fisher and starring Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing as Dracula and Van Helsing, which I saw when I was 13 years old. 13 is a formative age, when certain things tend to imprint themselves on your consciousness and become your favourites for life. Also, I feel uncomfortable saying this Nosferatu is better than Murnau’s Nosferatu. More than a century separates the two films, with huge differences in their historical contexts, themes, styles and filmmaking technology, and to me they’re like chalk and cheese. That said, I noticed some of the flaws in Eggers’ Nosferatu when I did compare it with the old one.

© Focus Features / Universal Pictures

While we’re on the subject of comparisons, I should say I massively preferred this film to the 1992 Francis Ford Coppola one, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Despite having the peerless Gary Oldman in the title role, it was one of the few films I’ve come close to walking out of in a cinema. I stayed the course in the hope it would improve in its later stages, but it didn’t. Eggers’ Nosferatu is as operatic in its tone and as flamboyant in its visuals as Coppola’s Dracula. However, while Coppola threw everything at the wall – restless camera movements, gimmicky special effects and make-up, over-the-top costumes, hammy performances – in the hope at least some of it would stick and hold the attentions of the raised-on-MTV teenagers he assumed would be the film’s audience, Eggers doesn’t merely show off In Nosferatu. There are also moments of stillness and silence, of subtlety and holding back, of allowing atmosphere to ferment and ripen. Actually, for my money, comparing it to Coppola’s Dracula is like comparing a moody and detail-laden work by a Dutch Master to a hyperactive kids’ cartoon.

Nosferatu’s storyline follows the Dracula template. Young estate agent Thomas Hutter (the stand-in for Stoker’s Jonathan Harker, here played by Nicholas Hoult) is despatched from the fictional German port-city of Wisburg to a castle in Transylvania, where he has to supervise the paperwork for the purchase of a Wisburg mansion by the mysterious Transylvanian aristocrat Count Orlok. Hutter’s sojourn in Orlok’s castle becomes a terrifying ordeal as he discovers the vampirical nature of his host. He ends up plunging from one of its windows, into a river, while the Count sets off for Wisburg.

The Count’s chosen mode of travel is by ship – Romania, which Transylvania is part of now, borders on the Black Sea and Germany’s coast runs along the North and Baltic Seas, so this is evidently a long voyage – and he brings with him a horde of plague-carrying rats, which first destroy the ship’s crew and then start infecting the citizens of Wisburg when he reaches his destination. These plague-rats are both a physical manifestation of Orlok’s evil and, presumably, a way of disguising his activities – with people dropping dead of plague left, right and centre, nobody’s going to notice a few blood-drained corpses.

But Orlok’s presence has been felt in Wisburg long before his arrival there. Hutter’s wife Ellen – the Nosferatu equivalent of Stoker’s Mina Harker – has had an inexplicable psychic link to the ghoulish Count since her childhood and has already, in her dreams, pledged herself to him. Also, Hutter’s boss Knock (Simon McBurney) has been communing with Orlok via some occult rituals. Sending Hutter off to Transylvania was clearly part of a plan to relocate the vampire to the feeding-grounds of Wisburg. Knock is the film’s version of Milo Renfield, the asylum-inmate who in Stoker’s novel becomes Dracula’s disciple. Accordingly, Knock goes insane, gets incarcerated, escapes and does Orlok’s bidding in the city. Meanwhile, the thirsty Count makes a beeline for Ellen and those around her…

© Focus Features / Universal Pictures

Eggers’ cast-members acquit themselves well. Lily-Rose Depp is extremely impressive in a role that requires her to be frightened, helpless, yearning, lascivious, possessed and defiant – often a couple of those things in one scene. As a female foil to Dracula, she’s as good as Eva Green’s character Vanessa Ives in John Logan’s gothic-horror TV show Penny Dreadful (2014-16). Likening someone to the mighty Eva Green is big praise from me.

Playing Jonathan Harker in a Dracula film is a thankless task. You have to be bland and bloodless enough to add spice to the forthcoming dalliance between your missus and the Count, to suggest she’s a desperate 19th-century housewife who might actually welcome the vampire’s kiss. But you also have to be interesting enough to make the audience root for you while you’re trapped in Castle Dracula. And Nicholas Hoult does what’s required as the Harker-esque Hutter. His restraint contrasts with the silent-movie acting of the original Hutter, Gustav von Wangenheim, who spent the early scenes of the 1922 Nosferatu grinning like a maniac.

On the other hand, Simon McBurney is unnervingly off-the-scale as Knock. The 1922 Knock, Alexander Granach, was off-the-scale too, but McBurney’s one is allowed to slather himself in some full-on, 2024-stye blood and gore. (He follows the hallowed Renfield tradition of chomping on small animals.) If there’s a criticism, it’s that he doesn’t get enough to do. More on that in a minute.

Ralph Ineson and Willem Dafoe respectively play a beleaguered Wisburg physician, Dr Sievers, and a Swiss expert on the occult, Professor Von Franz, who correspond to Stoker’s Dr Seward and Professor Van Helsing. When Hutter gets back to Wisburg, they team up with him to put a stop to Count Orlok’s onslaught. Willem Dafoe won’t replace Peter Cushing in my affections as the ultimate cinematic Van Helsing, but he’s delightful as the eccentric, cat-loving Von Franz. Kind old gent though he is, Von Franz concocts a plan to destroy the vampire that may have tragic consequences for the people he’s supposed to be protecting.

© Focus Features / Universal Pictures

As for Bill Skarsgård and the film’s depiction of Count Orlok… I can see why it’s been controversial. Some have been disappointed that Eggers and Skarsgård didn’t replicate the iconic look of actor Max Schreck, who played the Count in 1922 as a bald, gaunt creature with rodentlike incisors, Spock ears and unseemly tufts of ear and eyebrow hair. Indeed, in the first part of the film, we hardly see Orlok. During the scenes set in his castle, he’s unsettlingly obscured by a haze of firelight, candlelight, shadows and darkness. But when Eggers’ cameras finally reveal him, he’s an icky, mouldering thing, from the neck down at least, and he sports a monstrous and frankly distracting moustache.

I know Dracula had a moustache in the novel, and certain actors have played him with one, such as John Carradine in the Universal movies House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), and Christopher Lee in Jess Franco’s Count Dracula (1970). But this must be the droopiest, shaggiest Drac-tache ever.

Maybe Eggers avoided the Max-Schreck look because he was sensitive to the accusations of antisemitism that dogged the old Nosferatu – that Schreck’s Orlok played on common German stereotypes and caricatures of Jewish people at the time. Or maybe he just decided that look had become too much of a cliché. As well as a slap-headed, pointy-eared vampire featuring in the previous remake of Nosferatu, Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1977), similar ones have appeared in the 1979 TV version of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, the original film version of What We Do In The Shadows (2014), and Guillermo del Toro’s Blade II (2002), where the leader of the baldy-vampires was played by Luke Goss. (Yes… a Bros-feratu.)

© Focus Features / Universal Pictures

It’s also debatable if Eggers and Skarsgård made the right choice for Orlok’s loud, guttural voice, which booms out of the screen like the Voice of the Mysterons from Gerry Anderson’s TV show Captain Scarlet (1967-68) with a Slavic accent. At least it’s different… And Skarsgård put a lot of work into creating those vocals, training with an Icelandic opera singer and even studying Mongolian throat singing. But I actually found Yorkshireman Ralph Ineson’s deep, gruff, north-of-England tones more menacing, even though his character, Dr Sievers, is one of the good guys. (Sievers must have had a medical practice in Leeds before moving to Wisburg.)

Elsewhere, not a great deal happens during the second half of the film, though Dafoe’s charming performance keeps us engaged. The latter part of the 1922 film is enlivened by a sub-plot involving Knock, who gets blamed for the mayhem in Wisburg after Orlok’s ship arrives. Believing him to be the real vampire, the townspeople pursue him through the streets and the surrounding countryside, in scenes that are still impressive today – Knock perched like a gargoyle atop a vertiginous rooftop, for instance, or the mob mistaking a distant scarecrow for him, rushing at it and tearing it to pieces. Eggers removes this sub-plot, however, and Knock (who in the original film didn’t even meet Orlok physically) serves as a conventional vampire’s acolyte. If nothing else, this gives the Count someone to transport his coffin from the Wisburg docks to the mansion he’s bought. In the 1922 Nosferatu, he suffered the indignity of having to carry the coffin himself.

So, the film drifts somewhat later on and I’m not fully convinced by its portrayal of Count Orlok. But overall I really enjoyed Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu. It’s a feast – an Eggers’ banquet – of gorgeousness, gloom, sensuality, repulsiveness, grue, humour, absurdity and tragedy. It has fabulous visuals, entertaining performances and a smart balance between the aesthetically pleasing and the grotesquely yucky, meaning it should satisfy both cerebral arthouse types and horror-movie aficionados more interested in blood, gore and plague-rats.

And I can’t understand why some people disliked it so much. This Nosferatu isn’t Dross-feratu, it’s the Absolute-boss-feratu.

© Focus Features / Universal Pictures