© BBC

I’m currently halfway through William Boyd’s 2009 London-set thriller Ordinary Thunderstorms which, after a rather unengaging start, I’m happy to say is now shaping up to be a gripping read. It’s interesting how quickly Boyd’s plot, of an innocent man being accused of a murder he didn’t commit and having to go to ground – literally so, hiding in a neglected patch of waste ground by the Embankment – to avoid both the police and the real killers, reminded me of several other books, namely, John Buchan’s The 39 Steps (1915), Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male (1939) and, in a rather more skewed way, J.G. Ballard’s Concrete Island (1974).

It’s been a good while since I read The 39 Steps and Concrete Island, but I read Rogue Male just a couple of years ago and was impressed enough to post something about it on this blog. Here’s the entry again, slightly updated to incorporate some Benedict Cumberbatch-related news.

For a novel whose plot hinges around an attempt to kill Adolf Hitler, there’s remarkably little about Hitler in Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male. In fact, the genocidal German dictator isn’t mentioned once. Presumably this is because although Rogue Male first appeared in print in late 1939, after war had broken out between Britain and Germany, it was written before the outbreak of war when Household felt it would be diplomatic not to name names.

Thus, the book’s hero goes boar-hunting in Poland, crosses the border into a neighbouring country that isn’t identified, and one day ends up with the brutish leader of that country, also not identified, in the sights of his hunting rifle. Is he actually in Germany and on the point of bagging Hitler? Or could he be somewhere else, Russia say, where he’s targeting Joseph Stalin? But although Household keeps it ambiguous, given historical events soon after the story’s late-1930s setting, it’s impossible to read Rogue Male now and not visualise in those sights a bloke with a square-shaped scrap of a moustache, an oily side-parting and a swastika armband.

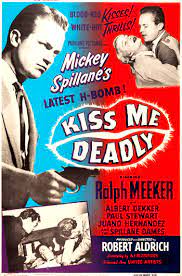

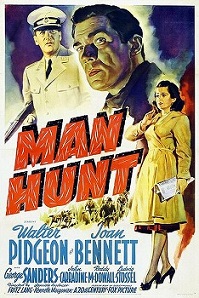

Incidentally, when Rogue Male was brought to the screen, the filmmakers didn’t follow Household’s ambiguity. A 1941 Hollywood adaptation called Manhunt, directed by Fritz Lang – who’d bailed out of Germany in 1933 after Joseph Goebbels started taking an interest in him – readily depicted the target as Hitler and, viewed today, the film feels like an unabashed wartime propaganda piece. Meanwhile, a 1976 adaptation by the BBC, directed by Clive Donner, was also unequivocal that its hero was going after Hitler. The actor playing Hitler was none other than Michael Sheard, fondly remembered by kids of my generation for playing Mr Bronson, the hard-nut deputy headmaster on the BBC’s children’s drama / soap opera Grange Hill (1978-2008).

Just as the book’s target is anonymous, so is its hero, even though he tells the story in the first person. Again, the film versions differ from the book in giving him an identity. In 1941’s Manhunt, he’s called Captain Thorndyke and is played by Walter Pidgeon. In 1976’s Rogue Male, he’s called Sir Robert Hunter and is played by the marvellous Peter O’Toole.

© Penguin Books

Whoever he is, he’s apprehended before he can fire the rifle and subjected to a brutal interrogation. Then his captors decide that the easiest way to deal with him is to bump him off and make his death look like an unfortunate hunting accident. The ensuing story can be divided into two parts, with each part having a similar, contracting, funnelling structure where the action begins in an expansive setting but ends in a cramped, claustrophobic one. First, Rogue Male’s hero manages to escape from his captors and is pursued by them across the countryside of whatever foreign nation he’s in. Okay, for the sake of simplicity, let’s just say his captors are the Gestapo and the nation is Germany. His pursuers close in but he manages to elude them by stowing away on a London-bound ship, hiding on board inside an empty water tank.

Then begins the second, longer part of the narrative. Back in Blighty, he discovers that Hitler’s agents are still on his trail. They don’t just want to eliminate him but also want to make him sign a document saying that he carried out his attempted assassination with the blessing of the British government. Again, the pursuit begins against a broad vista, this time the streets of London and landscapes of southern England. But again, his options narrow and eventually he digs and hides himself in a little cubbyhole under an unruly and remote hedgerow marking the boundary between two farms in Dorset.

One thing that surely inspired Rogue Male was Richard Connell’s short story The Hounds of Zaroff (1924) about a big-game hunter who gets hunted as game by another, even bigger-game hunter. However, while Household borrows this ironic scenario of a hunter becoming the hunted, he explores it with surprising depth. His hero obviously grew up in a rural aristocratic culture of shooting and hunting but he’s remarkably empathetic with the creatures on the receiving end of the bullets and hounds. He mentions once or twice that he got sick of hunting rabbits because of their harmlessness and defencelessness. And, holed up in his Dorset burrow, he becomes rabbit-like himself.

He also bonds with a cat living wild in the hedge above him, whom he names ‘Asmodeus’, presumably after the ‘worst of demons’ described in the Catholic and Orthodox Book of Tobit. At one point he speculates of Asmodeus, “there is, I believe, some slight thought transference between us… back and forth between us go thoughts of fear and disconnected dreams of action. I should call these dreams madness, did I not know they came from him and that his mind is, by our human standards, mad.”

Later, he comments, “I had begun to think as an animal; I was afraid but a little proud of it. Instinct, saving instinct, had preserved me time and again… Gone was my disgust with my burrow; gone my determination to take to open country whatever the difficulties of food and shelter. I didn’t think, didn’t reason. I was no longer the man who had challenged and nearly beaten all the cunning and loyalty of a first-class power. Living as a beast, I had become a beast, unable to question emotional stress, unable to distinguish danger in general from a particular source of danger.”

While Rogue Male’s central character becomes unhealthily animal-like, his main adversary is a hunter extraordinaire. A German agent masquerading as an English country gent called Major Quive-Smith appears on the scene, displaying impeccable upper-class charm towards the civilians he encounters, whist ruthlessly pursuing his quarry. Quive-Smith books a room in one of the farms adjacent to the hedge and burrow, pretending that he wants to spend a few weeks in the area doing some shooting. Spying on him from afar, Household’s narrator notes uneasily that “the major carried one of those awkward German weapons with a rifled barrel below the two gun barrels… the three barrels were admirably adapted to his purpose of ostensibly shooting rabbits while actually expecting bigger game.”

© 20th Century Fox

In addition to The Hounds of Zaroff, Household was probably influenced by John Buchan’s The 39 Steps (1915). But while there’s more to Buchan’s novel than its conventional action-adventure reputation would suggest, due to its recurrent theme of disguise and imposture, I think Rogue Male is superior in terms of characterisation and psychological tension. Buchan’s Richard Hannay is an outsider in that he’s a veteran of the African colonies who finds life back in the ‘Old Country’ stuffy, pretentious and tedious; but the hero of Rogue Male is an outsider in more complex ways. He comes from a world of wealth and entitlement but treats that world with indifference and it’s noticeable that when he’s back in London he has a lack of friends in high places to call upon for help. Indeed, he’s such a loner that at times you wonder if he wants to resign from the human race itself. This is even without the mental and physical stress of being hunted making him less like a man and more like an animal. Household provides a few clues about a past tragedy that may explain his disenchantment but wisely he doesn’t get bogged down in too much backstory.

And though Hannay is no shrinking violet, it’s doubtful if he could put with living for long in the burrow that the narrator digs for himself in Dorset and where he spends a good part of 90 pages, first hiding in it from Quive-Smith and his men, and then besieged in it by them. Household manages the tricky task of not overly describing the dirt, muck and claustrophobic darkness of this hideaway whilst implying its squalor. His hero is accustomed to it while he’s inside it but realises how horrible it is when he’s out of it and then comes back: “The stench was appalling. I had been out only half an hour, but that was enough for me to notice, as if it had been created by another person, the atmosphere in which I had been living.” Then again, like many men of his generation, he’s already undergone something traumatic that puts this experience in perspective: “…my God, I remembered that there were men at Ypres in 1915 whose dugouts were smaller and damper than mine!”

I’ve known the story of Rogue Male for a long time thanks to seeing the two film adaptations. I didn’t like the 1941 Hollywood version, which downplays the rawness of the novel and turns it into a conventional espionage thriller, reducing the amount of time Walter Pidgeon spends in the burrow and padding things out with extra characters and plot twists. The film’s low-point comes when Pidgeon gets off the ship and is greeted by a parade of Cockney Pearly Kings and Queens waltzing and singing down a foggy street. I guess that was the filmmakers’ way of assuring American audiences that, yes, he is back in London.

But I enjoyed the 1976 BBC version. Its scriptwriter, Frederick Raphael, streamlines parts of Household’s narrative and embellishes others – most notably, adding a new character, a pompous and unhelpful representative of the British government sublimely played by Alastair Sim – but it’s gritty and, for the time, brutal, even if Peter O’Toole never quite becomes the desperate, filthy, animalistic figure that his counterpart in the book becomes. In addition, it has a great cast (John Standing, Harold Pinter, Michael Byrne and Mark McManus as well as O’Toole and Sim) and it even slips in a cheeky visual reference to Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s wartime classic, The Life and Times of Colonel Blimp (1943).

And coincidentally, it looks like Rogue Male could be back in vogue. For the past few years, it’s been known that Benedict Cumberbatch wants to produce (and presumably star in) a new version of it. Let’s hope the Cumberbatch version, if it appears, is closer to the sombre tone of the 1976 adaptation than the anodyne, crowd-pleasing tone of the 1941 one. Or, better still, it makes a real effort to capture the fascinatingly introspective, misanthropic and grimy mood of the novel that inspired those versions in the first place.

© BBC