From wikipedia.org / © Nonsenseferret

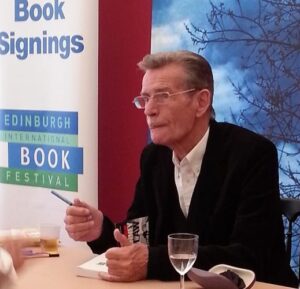

It’s exactly a decade since the Scottish writer, poet and columnist William McIlvanney passed away on December 5th, 2015. Here’s something to mark this melancholy anniversary.

For myself and many book-lovers in Scotland in the 1980s, William McIlvanney was both a source of pride and exasperation. Pride that modern Scottish literature was capable of producing someone as good as he was; but exasperation that the British literary establishment seemed to have little interest in him or his peers (like Alasdair Gray and James Kelman) north of the border. On their radar, Scottish writers didn’t make much of a blip.

Back then, the clique of authors, critics and academics who, through Britain’s highbrow media outlets, decided what was fashionable were a privileged Oxford / Cambridge-educated bunch who lived in London and seemingly lived up their own arses too. I always find it telling that in 1984, when things felt at their very worst, the Booker Prize – the flagship award for the UK literary establishment – managed to have on its short-list five books that had novelists, biographers, literary critics and literary lecturers as their main characters. The only shortlisted book that was about people who didn’t make a living out of literature (you know, like 99.999% of the human population) was J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun. And it didn’t win, though it should have.

The novel that helped put McIlvanney on the map was 1975’s Docherty, which was about a tough west-of-Scotland miner and his family trying to cope with everything that the early decades of the 20th century threw at them. Thus, McIlvanney was never going to ingratiate himself with the ‘in’ crowd by writing about writers, biographers, critics or lecturers either.

I’d read McIlvanney’s 1977 novel Laidlaw as a teenager – more about that in a minute – but it wasn’t until I was at college that one of my tutors (Isobel Murray) urged me to read a book of his that’d just been published, 1986’s The Big Man. I’m glad I listened to her because The Big Man proved to be one of my favourite books of the 1980s. It features another miner, called Dan Scoular. He’s an ex-miner, actually, because this is the post-miners’-strike 1980s, Scoular has lost his job and he and his family are struggling to make ends meet. The imposing Scoular happens to be good at fighting, though it’s a side of him that he’s suppressed for a long time. Then he’s approached by a Glaswegian gangster who offers to pay him a small fortune if he takes part in an illegal bare-knuckle fight. Thus, Scoular faces a dilemma – does he do something that he finds abhorrent if it saves him and his loved ones from penury? Inevitably, after he ignores his better instincts and agrees to the proposal, he finds out that there are more complicated and even nastier things going on in the background.

© Hodder and Stoughton

The Big Man is the most cinematic of McIlvanney’s books and it was no surprise that it was filmed, in 1990, by David Leland. The film gets some things right. The villains, played by Ian Bannen and Maurice Roëves, are good. However, it gets a lot wrong, including a Hollywood-esque, feel-good ending far removed from the bleak, ambiguous note with which McIlvanney closes the book. Another problem is that, at the time, there wasn’t a bankable-enough Scottish star for the filmmakers to cast in the role of Scoular. So they had to search around and the next best thing they could find was a Northern Irishman, Liam Neeson.

Now I like Neeson, but every time in The Big Man that he opens his mouth and those dulcet County Antrim tones of his emerge, the sense that you’re in a hard-pressed mining town in the West of Scotland goes out of the window. It’s a pity that the film wasn’t made during the years since, when some bankable Scottish actors have come to prominence (though it might be difficult to find one with the necessary, hulking physicality that Neeson had). Incidentally, The Big Man – a movie about Scottish ex-mining communities and ruthless Glasgow criminals – also has Hugh Grant in its cast. I’ll give you all a minute to pick your jaws up off the floor.

A later novel by McIlvanney, 1996’s The Kiln, received a lot of acclaim. It even had a recommendation on its cover from Sean Connery. I’ve just praised McIlvanney for not writing books about writers, but The Kiln actually has a writer as its central character, one in the throes of a mid-life crisis. However, the novel is more a coming-of-age novel because its hero spends much of it looking back on his working-class youth, especially on a period he spent toiling in a local brickworks.

When The Kiln appeared, it seemed to cement – an appropriate verb for a book about bricks – McIlvanney’s status as a major figure in Scottish letters. But it seemed the last time that he commanded such attention. Recently, I was thinking about The Kiln and I remembered reading it while I was making a long-distance bus trip during the only occasion I was in Australia – which was in 1997, almost thirty years ago and almost twenty years before McIlvanney’s death. What on earth happened to him after that? I’d come across an occasional interview with him or article by him in the Scottish press, but that was about it. In 2006 he published one more novel, Weekend, though it arrived with little fanfare – the antithesis of the reception The Kiln got a decade earlier.

© Hodder and Stoughton

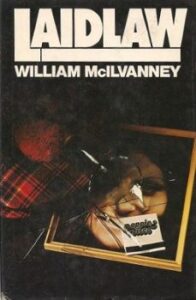

Though as far as mainstream literature was concerned McIlvanney seemed to disappear from view after The Kiln, he did in recent years win belated acknowledgement for his work as a crime writer – specifically, for his 1977 novel Laidlaw, which was republished in 2013, and its sequels The Papers of Tony Veitch (1983) and Strange Loyalties (1991). (The latter book also serves as a grim semi-sequel to The Big Man.) All are about a tough but intellectual and philosophical Glasgow detective called Jack Laidlaw. Since then, crime novels set in Scotland have sold by the barrow-load and Scottish crime writers like Iain Rankin, Val McDiarmid, Denise Mina, Christopher Brookmyre and Stuart MacBride have enjoyed lucrative careers, so McIlvanney can be seen as the man who started it all. His Jack Laidlaw was the prototype for Inspector Rebus and the rest. In effect, McIlvanney created ‘Tartan Noir’.

Even when I read Laidlaw at a young age, I found it a bit uneven (as prototypes usually are), its prose shifting slightly uncomfortably between Glasgow-speak and Raymond Chandler-isms. It wasn’t helped by the way it was marketed, either – “Turn down a Glaswegian when he offers you a drink,” intoned the blurb on the back, “And he’ll break your legs,” which wasn’t what the book was about. Laidlaw focuses more on psychology than on violence, and I found it disconcerting that in its final pages the hero isn’t rushing to catch the murderer so much as he’s rushing to save the murderer from gangland-backed vigilante justice. But all power to McIlvanney for inventing what would become Scotland’s biggest literary export. Iain Rankin, in particular, has always admitted his debt to him.

McIlvanney was a political thinker too and during the 1990s – back in those long-ago days when Scotsman Publications produced material that was worth reading – he was a perceptive columnist in the Scotland on Sunday newspaper. I also remember him delivering a speech in Edinburgh’s Meadows during the March for Scottish Democracy rally held on December 12th, 1992, demanding the creation of a Scottish parliament. On stage, in front a crowd of 30,000 people, he performed far better than any of the politicians in attendance. He memorably summed up the case for a parliament saying: “We gather here like refugees in the capital of our own country, wondering what we want to be when we grow up. Scotland – the oldest teenager amongst nations.”

But at the same time he pleaded for racial tolerance. “Scottishness,” he pointed out, “isn’t some pedigree lineage. It’s a mongrel tradition.” I suspect that with McIlvanney’s speech that day began the emphasis on ‘civic nationalism’ that Scottish nationalists – at least, the decent, mainstream ones, not the fringe, far-right heidbangers – have been at pains to cultivate ever since.

Finally, William McIlvanney played an indirect role in the start of my writing career. My very first short story to see publication, a slice-of-life piece set on a Scottish farm with the self-explanatory title Lambing Time, appeared in a magazine called Scratchings, then produced annually by Aberdeen University’s Creative Writing Society. Scratchings had been launched in the early 1980s with the help of a financial contribution from McIlvanney. At the time he was Aberdeen University’s writer-in-residence and he was approached by two young students who “wanted to borrow 40 pounds to start a poetry magazine. Would he be able to lend them the money?” He did, Scratchings was born, and it provided a home for Lambing Time a few years later.

Incidentally, the two students who successfully tapped McIlvanney for 40 pounds were Dundonian Kenny Farquharson, now a columnist with the Times newspaper; and Invernessian Alison Smith, now better known as the novelist Ali Smith, who’s been shortlisted three times for the Booker Prize – yes, the award whose shortlist bugged me so much back in 1984.

© Hodder and Stoughton