© Tuttle

And another Halloween-inspired post…

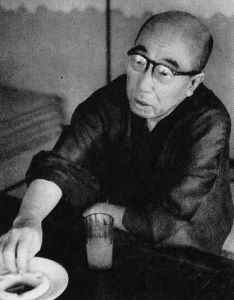

Japanese writer Hirai Taro, who lived from 1894 to 1965, was such a fan of Edgar Allan Poe, America’s doyen of macabre and mysterious fiction, that he used the penname ‘Edogawa Rampo’. English-language names sound somewhat stretched and distorted when converted to the syllable-systems of Japanese – my own name is pronounced ‘Ee-an Sumisu’ – and Taro’s penname was basically a Japan-ised version of ‘Edgar Allan Poe’. Say ‘Edogawa Rampo’ quickly a few times and you’ll find yourself reciting the name of Baltimore’s greatest man of letters.

Accordingly, during his literary career, Rampo wrote in similar genres to Poe. He didn’t merely pen horror stories. Poe’s name is now so synonymous in the West with tales of terror like The Tell-Tale Heart (1843), The Masque of the Red Death (1842), The Fall of the House of Usher (1839), The Pit and the Pendulum (1842), The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar (1845) and so on that it’s often forgotten how innovative he was working in other genres. In particular, he helped create the detective story with his trilogy of stories about crime investigator C. Auguste Dupin, The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), The Mystery of Maire Roget (1842) and The Purloined Letter (1844). And it was largely in detective and crime fiction that Rampo made his name. He even helped to found the Japanese Mystery Writers’ Club.

Rampo’s Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1956) is an English-language collection of nine of his best short stories. Not only does it take its name from Tales of Mystery and Imagination, described by Wikipedia as ‘a popular title for posthumous compilations of writings by American author, essayist and poet Edgar Allan Poe’, but it combines stories from those two genres Poe helped to popularise in the early 19th century, the horror and the detective / mystery ones. It has to be said the two styles mesh together nicely in this collection. There’s a weirdness in Rampo’s detective fiction that ensures it doesn’t feel that different, tonally, from his morbid horror stories.

Among the crime stories, you get villains attempting to commit the perfect murder with schemes that involve living a double life as an invented character (The Cliff), impersonating someone who looks exactly like them (The Twins) and the fear of sleepwalkers that they might do something ghastly whilst moving in a trance-like state (Two Crippled Men). All three have a last-minute twist wherein the main characters get their come-uppance from someone who’s even smarter than they are, or by a small but fatal act of negligence – the sort of minor blunder that would have Peter Falk’s Lieutenant Columbo swooping down like a hawk. Talking of Falk’s beloved shabby-but-canny TV detective, The Psychological Test is a very Columbo-esque tale of how a pair of investigators use an ingenious method to get a suspect in a murder case to incriminate himself.

Meanwhile, The Red Chamber takes a trope popular in 19th and early 20th century English fiction, that of a comfortable, wooden-panelled gentlemen’s club where the tweedy members congregate after dark and, with the lights turned down, proceed to tell each other scary stories. In Rampo’s gentlemen’s club, however, things get shaken up when the evening’s storyteller, a newcomer, boasts about being responsible for “the murder of nearly a hundred people, all as yet undetected’ and proceeds to explain how he did it and got away with it. Several harrowing twists later, it’s no surprise that the story’s narrator, a long-term member of the club, concludes: “…we unanimously agreed to disband.”

The other four stories in Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination are macabre ones. They possess the same oddness and intensity of his crime stories, but cranked up to higher levels. The Hell of Mirrors is about a man who becomes obsessed with optics, with ‘anything capable of reflecting an image… magic lanterns, telescopes, magnifying glasses, kaleidoscopes, prisms and the like’ and with mirrors: ‘concave, convex, corrugated, prismatic.’ Typically with Rampo’s fiction, this obsession spills over into another obsession, a sexual one. The protagonist is soon using telescopes to pry through the windows of his female neighbours and using periscopes to ‘get a full view of the rooms of his many young maidservants.’ The story reaches its climax when he devises a mirrored, optical device so depraved it ultimately induces madness.

The Traveller with the Pasted Rag Picture, on the other hand, is the one Rampo story in this collection that veers off into the supernatural. It reminded me very slightly of the M.R. James story The Mezzotint, though the picture in that story was a spookily lifelike one that recorded a horrific event. In Rampo’s story, a similarly lifelike picture serves as a testimony to a sad, doomed and one-sided romance.

That leaves two stories, The Human Chair and The Caterpillar, which I think are masterpieces. The Human Chair concerns an ugly and reclusive craftsman who makes a living fashioning luxurious chairs, whilst getting a perverse kick out of imagining ‘the types of people who would eventually curl up’ in them. Eventually, driven insane by his desire to get intimate with the folk who’ll acquire and use his chairs, he designs a bulky one containing a secret, human-sized cavity, inside which he hides himself. The chair and its maker end up in a hotel lobby, where the latter gets his jollies from feeling the bodies of the guests rest on top of him. No one “suspected even for a fleeting moment that the soft ‘cushion’ on which they were sitting was actually human flesh with blood circulating in its veins – confined in a strange world of darkness.”

The story is told in the form of a confession, sent as a letter to a famous lady novelist. While she reads it, she begins to wonder about the suspiciously large and comfy chair she’s seated in, which has found its way to her study after being in a hotel. There comes a final twist that nullifies what’s happened before – or perhaps doesn’t.

The Caterpillar, written in 1929, is an early, literary example of ‘body horror’. The central character is an unfortunate young army officer so maimed and mutilated in battle that he comes home resembling the larval-form insect of the title. This puts understandable strain on the officer’s wife, upon whom, totally helpless, he depends for care and attention. In fact, The Caterpillar is more about the wife than the husband, with the hideous situation gradually pushing her into the realms of madness – of sadistic madness, because she starts taking her woes out on her husband, who can’t do anything to defend himself. The story works both as a feminist tract, showing the plight of women whom society expects to be wholly devoted and subservient to their husbands, and as a horror story exploiting male fears of emasculation. It’s a grim and powerful read, packing as much of a punch as it did when it first appeared, nearly a century ago.

I think the original Edgar Allan Poe would approve of Rampo’s tales. They’re deliciously dark and twisted, and frequently ingenious, and sometimes funny too – a lot of the humour derives from how his villains, when telling their stories, like to revel in their own cleverness and degeneracy. It’s just a pity that Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination is the only English-language collection by Rampo I’ve come across. I’d really like to read more of his stuff. Unlike a certain character played by Sylvester Stallone, I wouldn’t mind seeing a Rampo 2, Rampo 3, Rampo 4 and Rampo 5.

From wikipedia.org / © The Mainichi Graphic