© Goodtimes Enterprises / Warner Bros.

Oh God. I’ve just discovered that the soundtrack of Melania (2026), the vanity-documentary about Melania Trump, financed by Jeff Bezos and directed by Brett Ratner – a man accused of sexual assault by six women (allegations Ratner has always denied) – contains a song I just might identify as my favourite one of all time. That is Gimme Shelter, the opening track on the Rolling Stones’ 1969 album Let It Bleed. Yes, a tune that means so much to me features in a movie pithily described by Mikey Smith, deputy political editor at the Daily Mirror, as ‘a bad film made by bad people about bad people’, and about which Variety suggested if they showed it on an airplane ‘people would still walk out’. I feel besmirched.

It’s quite possible, though, that the Trumps and Brett Ratner bunged Gimme Shelter onto the soundtrack without actually listening to the words. Supposedly played as an accompaniment to Melania’s preparations for her husband’s inauguration as 47th President of the USA, which one year later would lead to masked, paramilitary-style thugs abducting young children from their homes and schools and executing peaceful protesters on the street, the song has such lyrics as “Rape, murder / It’s just a shot away” and “War, children / It’s just a shot away.” Very apt, when you think about it.

Anyway, this has at least got me thinking about a different, and nicer, Rolling Stones-related topic – the band and movies. After all, over the years, there have been plenty of Beatles films: A Hard Day’s Night (1964), Help! (1965), Yellow Submarine (1968), Let It Be (1970), I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978), The Birth of the Beatles (1979), Give my Regards to Broad Street (1984), The Hours and Times (1991), Backbeat (1994), Two of Us (2000), The Beatles: Get Back (2021) (which is actually a miniseries, but Peter Jackson made it, so it feels like a movie to me) and Sam Mendes’s forthcoming project, The Beatles – A Four-Film Cinematic Event (2027). But what about the Rolling Stones? What contribution to cinema has been made by the Liverpudlian mop-tops’ less wholesome London rivals?

© Shangri-La Entertainment / Paramount Classics

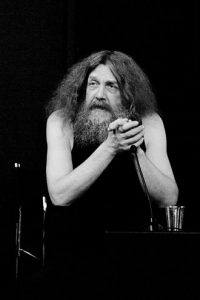

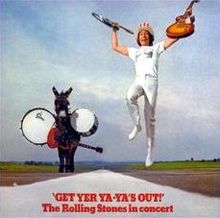

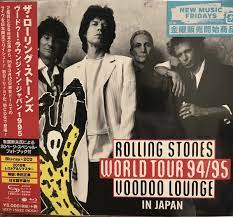

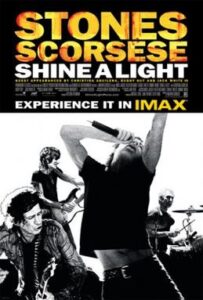

On the face of it, there isn’t a lot. That is, if you don’t count the various documentaries made about them like Charlie is my Darling (1966), Jean Luc Godard’s oddball Sympathy for the Devil (1968) and Gimme Shelter (1970), a chronicle of their 1969 American tour that ended bloodily with Hells Angels-perpetrated carnage at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival. And if you don’t count their many concert movies like The Stones in the Park (1969), Let’s Spend the Night Together (1982), Julien Temple’s The Stones at the Max (1991) (the first feature-length movie to be filmed in IMAX – because what you really want to see is a 100-feet-tall close-up of Keith Richards’ face, right?), The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus (1996) (plug your ears for the bit with Yoko Ono) and the Martin Scorsese-directed Shine a Light (2008), which provided the gruesome spectacle of a leathery 60-something Jagger duetting with 20-something pop-moppet Christina Aguilera and prowling around her like a randy velociraptor.

There’s been little effort to film key events in the history of the Rolling Stones. Off the top of my head, the only one I can think of is the little-known Stoned (2005), about the possible circumstances of Brian Jones’s death. And as for movies featuring Stones-members as actors, well, there’s just a couple of items with Mick Jagger – epics such as Ned Kelly (1970) and Freejack (1992). Ouch.

Actually, you could make a case for the Pirates of the Caribbean series being Rolling Stones films as their star Johnny Depp famously based the voice, mannerisms and swagger of his Captain Jack Sparrow character on Keith Richards. I thought Depp-playing-Keith-playing-a-pirate was a rib-tickling gimmick that elevated the first Pirates of the Caribbean instalment, back in 2003, from being a middling film to being an entertaining one. Alas, the sequels to it became ever-more convoluted, repetitious and tedious and, by the time of the third in the franchise, At World’s End (2007), when the filmmakers had the bright idea of bringing in the real Keith Richards to cameo as Captain Jack’s pirate dad, the idea had lost its novelty value.

© Buena Vista / Walt Disney Productions / Jerry Bruckheimer Films

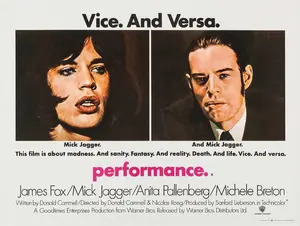

Arguably, the most Rolling Stones-esque film of all is Performance (1968), the psychedelically weird crime-rock movie co-directed by Donald Cammell and Nicholas Roeg. Its cast includes Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg, then lover of Keith Richards. The story of an on-the-run gangster (James Fox) who holes up in a mansion belonging to a burnt-out rock star (Jagger) and gets involved in some mind-bendingly druggy goings-on, the film neatly captures the dark, dangerous aura that was popularly associated with the Stones at the time. Neither did it do the film’s scary reputation any harm that afterwards Fox underwent a ‘crisis’, dropped out of acting for the next decade-and-a-half and became an evangelical Christian. As if the poor man hadn’t suffered enough, during the late 2010s, his son Laurence came out of the closet as an entitled-but-whinging far-right-wing rentagob.

Keith Richards had and still has a deep-rooted aversion to Performance, thanks to the sexual shenanigans that Pallenberg supposedly got up to with Jagger during filming. He believed these shenanigans were orchestrated by Donald Cammell, presumably as a way of getting Pallenberg and Jagger further ‘in character’. In his autobiography Life (2020) – which was written with the help of a journalist also, confusingly, called James Fox – Richards describes Cammell as “the most destructive little turd I have ever met.”

Because of Richards’ loathing of Performance, one Jagger-Richards song that’s never been played at Rolling Stones gigs and is unlikely to ever be played at future ones is Memo from Turner (1968), which soundtracks a particularly strange sequence at the movie’s climax when everyone is out of their faces, the gangsters start stripping off and Jagger dances amid veering lights. On the Performance recording of the song, Jagger is the only Stone involved, doing vocal duties, while Ry Cooder plays slide-guitar (wonderfully) and Randy Newman plays piano. It’s a shame that we’ll never hear a live Stones version of it because it’s a belter. I’m also partial to this cover of it by forgotten 1980s retro-rockers Diesel Park West.

Anyway, there’s one thing you can say about the Rolling Stones and celluloid. In the right film, blasting over the soundtrack at the right moment, a Stones song can help create a splendid musical, visual and dramatic alchemy, turning a good cinematic scene into one that’s truly awesome. In Part 2 of this post, I’ll list my favourite uses of Rolling Stones songs in the movies. Stay tuned…

© Goodtimes Enterprises / Warner Bros.