From wikipedia.org / © Nicolas Genin

As Halloween approaches, here’s another entry with an appropriately creepy theme. This time it’s a piece about one of my all-time favourite filmmakers in the horror genre.

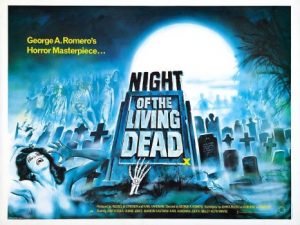

George A. Romero’s 1968 debut was Night of the Living Dead, a movie that’s been stupendously influential in at least three ways. Firstly, it was filmed during nights and weekends over a period of seven months for a paltry $114,000. The famous opening sequence took place in Pittsburgh’s out-of-town Evans City Cemetery for the simple reason that Romero figured he could film there for free, on the quiet, without getting hassled by the police. Its success became a lasting inspiration for low-budget filmmakers everywhere, showing that with enough ingenuity, determination and talent you could accomplish something out of next-to-nothing. No doubt when things were getting tough during the shoots of landmark but ultra-cheap horror films like the $300,000-budget Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) or the $350,000-budget Evil Dead (1981) or the $60,000-budget Blair Witch Project (1999), their respective directors Tobe Hooper, Sam Raimi and Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez consoled themselves with the thought, “If old George could do it, so can I.”

Secondly, Night of the Living Dead wrestled horror movies away from the gothic costume dramas made by the likes of Hammer Films in Britain, Mario Bava in Italy and Roger Corman in the USA, which by the mid-1960s had become their comfort zone. It dragged the genre into the present day and made it visceral, nihilistic and properly frightening. The human characters having to cope with the horrible events in Night were ordinary Joes like those sitting watching them in the cinema audience. This could happen to you, it was telling them. And as none of those human characters got through the titular night alive, you really didn’t want it to happen to you.

Thirdly, Night introduced the world to zombies as it knows them today. And today popular culture is swarming with them, not only in blockbuster Hollywood movies like World War Z (2013) but in other media like TV shows, computer games, books and comics. Whereas before Night zombies had been depicted as poor, lost souls brought back to life by cruel, capitalist zombie-masters using the power of voodoo and put to work in flour-mills and tin-mines, as in Universal’s White Zombie (1932) and Hammer’s Plague of the Zombies (1966), after Night they had a new template. They became apocalyptic. They rose from the dead in hundreds, then thousands, and then millions, and fed on living humanity in scenes employing as much blood and gore as the movie-censors would allow. If they bit you, you got infected, died and became a zombie yourself. And the only way to stop the shambling, bite-y bastards was to “shoot ’em in the head”.

What I like about zombies of the Night of the Living Dead variety is that though they are mindless creatures, the movies themselves don’t have to be mindless. Those shambling zombies can be a metaphor for all sorts of things – for proletarian workers, consumers, oppressed peoples, whatever – giving filmmakers endless opportunities for social comment. Thus, Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) reflects a modern Britain where anger is an increasingly common social phenomenon and terms like ‘road rage’ and ‘air rage’ have entered the popular vocabulary; its sequel Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s 28 Weeks Later (2007) is an allegory about the post-war occupation of Iraq; and Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead (2004) satirises a twenty-something slacker generation who can’t tell if someone’s a zombie or just pissed, hungover or stoned. And again, Romero set the agenda with Night, which channels the fears of late-1960s America. The country’s racial tensions are symbolised by the fate of the black hero (Duane Jones), who survives the zombie onslaught only to be mistaken for one himself and shot dead by a supposed rescue-posse of trigger-happy rednecks. Meanwhile, the rednecks’ zombie-shooting / burning activities are not unlike things going on in Vietnam at the time.

© Image Ten / Laurel Group

However, Night of the Living Dead wasn’t the first George A. Romero film I saw. That honour belongs to a movie he made five years later called The Crazies, which turned up on late-night British TV in the 1970s. The Crazies has similarities to Night but isn’t a zombie movie because it features people turning into murderous lunatics rather than into murderous walking corpses. The story of the US Army trying, and failing, to contain a virus that gradually infects the population of a small rural town and drives them insane, The Crazies sees Romero giving the military a kicking.

It’s the army who’ve secretly developed the virus as a potential biological weapon; who accidentally let it escape into the town’s water supply; and who prove useless in trying to maintain order – this is a rural American community and there are a lot of guns, and before long it isn’t just the infected townspeople who are violently resisting the gas-masked, biohazard-suited soldiers. The army also bring in scientists to try to develop a vaccine but give them hopeless facilities – the local school’s science lab – and when one of them accidentally does stumble across a vaccine, more military bungling leads to his death and the smashing of the vital test tubes. At the film’s end, they even fail to do an immunity test on the hero, who by now is the only uninfected person left in the town.

The Crazies isn’t perfect. Its low budget sometimes means there’s a visible gap between what Romero aspires to and what he achieves on screen. But to my 13-year-old mind its blend of anarchy, violence, rebelliousness and, yes, humour was astonishing. I’ve never forgotten scenes like the one where a soldier bursts into a rural homestead and encounters a sweet old granny doing some knitting, who then stabs him to death with a knitting needle. A remake appeared in 2010 and, while it has some good moments, it’s ultimately unsatisfying. This is largely because it focuses on the civilian characters and hardly shows anything of the military ones. It’s the soldiers and their half-comical, half-horrifying ineptitude that makes the original so effective and enjoyable.

© Cambist Films

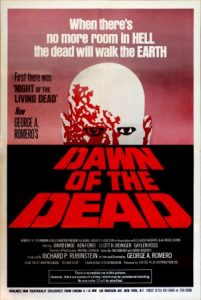

In 1978, Romero returned to bona-fide zombie moviemaking with Dawn of the Dead. The shopping malls spreading across the American landscape at the time inspired him to revisit Night’s zombie apocalypse and film a more expensive and expansive sequel. This has four survivors, led by black actor Ken Foree, taking refuge in an abandoned mall and fortifying it against the living dead. Romero uses the setting to poke fun at the sterility of consumerism, with the foursome’s lives rapidly growing tedious despite their unlimited access to everything in the mall’s stores. He also shows its idiocy. When more survivors show up, the two groups fight for possession of the building, though it contains enough supplies for everybody. The zombies, meanwhile, become irrelevant.

The shots of zombies shuffling mindlessly through the mall’s aisles and thoroughfares, staring with glazed eyes at the goods on display, aren’t subtle. The satire is sledgehammering. But hey, Romero’s satire works. 45 years on, whenever I find myself in a shopping mall, I soon start imagining the shoppers around me not as human beings but as lumbering cadavers. Also, in keeping with its theme of excess, Dawn piles on the bloodletting, courtesy of Romero’s regular special-effects man Tom Savini. In the opening minutes, Romero and Savini treat us to a close-up of an exploding head and the gore rarely relents after that.

© Laurel Group Inc

Dawn has been remade too, with a Zack Snyder-directed Dawn of the Dead appearing in 2004. It’s a film I have mixed feelings about. On the one hand, the first 25 minutes are terrific and I love the credits sequence, which shows a montage of clips and images of unfolding zombie carnage accompanied by Johnny Cash singing The Man Comes Around (2002). On the other hand, the film is devoid of satire. The living dead spend nearly all the film not being in the mall, so there’s no identification of shambling zombies with shambling shoppers, and you get a general impression of things being played safe. It’s a shame, as Naomi Klein’s anti-globalisation polemic No Logo (1999) had been published a few years earlier and a big gory horror movie poking fun at brainless brand-hungry consumerism and mindless corporate greed would have been just the ticket.

In 1986, Romero wrapped up his original zombie trilogy with Day of the Dead, which like The Crazies shows his utter contempt for the military – though by now his contempt for humanity generally seems intense too. Day has the world overrun with zombies and focuses on an elite band of scientists and soldiers holed up in an underground nuclear missile silo, desperately trying to find a solution for the mayhem happening above. Bitter arguments between the obsessed scientists and the brutish military eventually escalate into all-out warfare. When the zombies swarm in at the end, they seem the least mindless members of the cast.

Admittedly, Day has a couple of sympathetic humans, namely a philosophical Jamaican pilot played by Terry Alexander – Romero’s third black zombie-movie hero – and a somewhat alcohol-pickled Irish radio operator (Jarlath Conroy), both of whom realise the battle has already been lost. They just want to escape the silo, abandon the mainland and start afresh on a desert island. However, the film’s most likeable character is actually a zombie, one nicknamed Bub (Sherman Howard) who’s been captured by the scientists and domesticated… sort of. He can listen to music, pick up a phone and almost whisper a couple of words. He has vague memories of his former life, when he was a soldier, because he knows how to salute and hold a gun. He’s very fond of the scientist who looks after him (Richard Liberty) and when that scientist is murdered by the repellent Captain Rhodes (Joe Pilato), he’s genuinely upset and you feel genuinely sorry for him. And a climactic scene where Rhodes is torn apart by Bub’s zombie compadres while Bub looks on and gives him a farewell salute is one of the most satisfying moments in horror-film history.

© Laurel Entertainment Inc

On a more intimate scale than Dawn, with more talk and less action, Day was regarded as a disappointment by Romero enthusiasts when it was first released. However, over the years, its reputation has improved. It’s my favourite Romero movie and one of my favourite horror movies generally. Meanwhile – surprise! – a remake appeared in 2008. Unlike the other remakes I’ve mentioned, this one is absolute shite.

After Zack Snyder’s version of Dawn of the Dead made a lot of cash in 2004, Romero got the go-ahead, and considerable studio money, to make his first zombie picture in nearly 20 years. The result was 2005’s Land of the Dead which, although it received some decent reviews, was disdained by many hardcore horror-film fans who saw it as evidence that Romero had sold out or lost his touch. I think that’s unfair as, to me, Land is three-quarters of a good movie. Its opening sequence is superb, showing an abandoned (by humans) suburb whose zombie inhabitants now potter around in the way they did when they were alive. A zombie commuter lumbers out of his front door with a dusty briefcase, some zombie musicians pathetically try to play their old instruments at the local bandstand and a zombie gas-station attendant shuffles dutifully to his pumps whenever something sets off the motion-sensor bell in his hut.

I also like the movie’s set-up. Presumably taking place several years after Night, Dawn and Day, Land has Dennis Hopper as a megalomaniac who’s created a human sanctuary (bounded by a river and an electric fence) in the middle of a decaying city. There, the rich and powerful humans live in a luxury apartment block called Fiddler’s Green while the less well-off live in Dickensian squalor in the streets below. To keep his society going, Hopper regularly sends out a military force into the surrounding wasteland in a huge armoured vehicle called the Dead Reckoning, which is half-tank and half-truck, to scavenge for supplies. Trouble is, the zombies inhabiting the wasteland are developing rudimentary powers of thought and self-organisation and, miffed at getting splattered by Hopper’s military expeditions, they start to march towards his little enclave. Their leader is the afore-mentioned petrol pump attendant, played by black actor Eugene Clark. In a series where the hero has always been black, this suggests Romero has now totally sided with the zombies.

Parallels with America’s growing wealth inequalities, its oil-driven foreign adventures and rising anti-American sentiment in the Middle East during the noughties are no doubt fully intentional. I’d assumed that the Dennis Hopper character in Land represented George Bush Jr. However, as the critic Kim Newman pointed out in an obituary for Romero in Sight and Sound magazine, the character is actually a property developer. So maybe Romero had a premonition of who’d be sitting in the Oval Office at the start of 2017 (and quite likely again at the start of 2025).

© Atmosphere-Entertainment MM / Romero-Grunwald Productions

Land’s main problem is that it’s anti-climactic. The end scenes where the zombies penetrate the human enclave and then Fiddler’s Green are suitably gory and carnage-ridden. But you’re waiting for the military force in the Dead Reckoning, led by Simon Baker and Asia Argento, to ride to the rescue and start kicking serious zombie ass. When Baker, Argento and the gang finally arrive, though, all they do is blow up the electric fence to allow a few survivors to escape. And that’s it.

Still, Land is way better than the two zombie pictures Romero made subsequently. 2007’s Diary of the Dead has an interesting premise. It’s a found-footage movie about a group of young filmmakers who’re working far from home when a zombie apocalypse breaks out; and they decide to record their adventures on film, documentary-style, as they journey across an increasingly chaotic landscape. What’s particularly interesting is how they intercut their own story with clips that people around the world are simultaneously uploading to the Internet. This being Romero, those clips often show human beings taking advantage of the mayhem to act appallingly. However, after a gripping opening section, the middle of the film becomes predictable; and its final stretch is talky and ponderous to an extreme.

Survival of the Dead followed in 2009. Set on an island off America’s northwest coast where a feud between two families escalates while society breaks down around them, it resembles an especially scrappy episode of The Walking Dead TV show (2010-22) and is a sad final instalment in Romero’s zombie sextet.

In between zombies, Romero made other types of movies and a couple are very good indeed. That said, I’m not a fan of his two collaborations with Stephen King, Creepshow (1982), an anthology film scripted by King in the style of the old EC horror comics, and The Dark Half (1993), an adaptation of one of King’s novels. Creepshow has its admirers and features an excellent cast – Adrienne Barbeau, Ted Danson, Ed Harris, Hal Holbrook, E.G. Marshall, Leslie Nielson and Fritz Weaver – but I find it unnecessarily hokey and slightly unworthy of Romero’s talents.

© Libra Films International

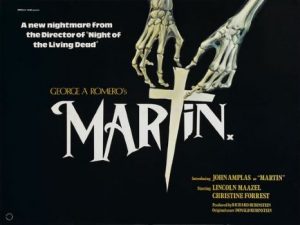

But Martin (1978) is excellent. It’s about a modern-day American teenager (John Amplas) who, clearly mentally disturbed, believes himself to be an 84-year-old vampire. He ends up living in the Pittsburgh suburbs with his great-uncle, an elderly Lithuanian immigrant. Steeped in the lore and superstitions of his old country, the great-uncle is only too happy to take him at his word. A disorientating mixture of blood-spilling, dreaminess, humour and melancholia, Martin is worth seeing as a tonic to those wimpy Twilight books (2005-20) and movies (2008-12) that have defined teenaged vampires in the 21st century.

Also praiseworthy is Romero’s 1981 non-horror movie Knightriders, which has a young Ed Harris in charge of a travelling medieval-style fair where the central attraction is the re-enactment of knightly jousting tournaments. The gimmick is that there isn’t a horse in sight. The knights doing the jousting are bikers riding (and regularly falling off) motorcycles. Furthermore, Harris, who sees his fair not as a business but a community, tries to live according to a knightly code of virtue and honour. This does him few favours as the fair suffers money problems and attracts unwelcome attention from bloodsucking promoters and talent scouts, sensationalist journalists, crooked cops, rival motorcycle gangs and redneck crowds who just want to see motorbikes getting smashed. Knightriders is overlong and meandering, has about 15 characters too many and is sometimes sentimental, melodramatic and hippy-dippy. But it’s also endearingly high-minded and decent-hearted. It again shows Romero’s disdain for materialism and mindless conformism, though this time in human rather than metaphorical terms.

© Laurel Productions

And Harris’s struggles in Knightriders reflect Romero’s uncomfortable relationship with the wider moviemaking industry, an industry that was all-too-happy to ignore him, exploit him, mess him around and rip him off. It was still doing this to him near the end of his life. Indeed, during the years before his death in 2017, Romero’s work that saw the light of day was in computer games and comic books. None of his film projects came to fruition after 2009.

In closing, I’ll say this to the spirit of George A. Romero. Sir, you were responsible for half-a-dozen movies – the original Dead trilogy, The Crazies, Martin and Knightriders – that are special ones for me. I salute you.

© Laurel Entertainment Inc