Sri Lanka is currently in the middle of another Covid-19-inspired lockdown. This is a 24/7 lockdown with nobody but police, health-workers, delivery staff and other essential service workers allowed to move around outside, so it’s a curfew basically.

This curfew was imposed by stealth. Originally, it was meant to last from the night of May 13th to the morning of May 17th, keeping people off the streets for a weekend. Afterwards, for the rest of the month, people whose National Identity Card numbers (passport numbers if you were a foreigner) ended in an odd digit would be allowed out on odd-numbered days and those whose numbers ended in an even digit would be allowed out on even-numbered days.

However, another weekend lockdown was imposed from May 20th until May 25th and we were warned that a further one was planned from the 25th to 28th, which would keep people indoors during the Vesak Festival on May 26th. Then it was announced that this lockdown would be extended until June 7th, with a couple of days along the way designated as ones when people could nip out to buy provisions. And then it transpired that those days when lockdown would be lifted wouldn’t actually happen, leaving the population with a 12-day stretch of home confinement until June 7th.

Who knows? It wouldn’t surprise me if this lockdown gets extended again beyond the 7th. 36 people died of Covid-19 yesterday, a fairly typical daily number during the past few weeks, so the emergency remains.

Generally, since the Covid-19 epidemic began, my partner and I felt quite fortunate to be in Sri Lanka because, overall, the island seemed to have done a reasonable job of dealing with it. After a strict initial lockdown last year, from March to May, the virus seemed to be contained. For months afterwards, while the virus wreaked havoc in supposedly more developed countries like the UK and USA, the Sri Lankan death toll remained static with fatalities only in the teens.

This changed in early October 2020 with the appearance of a major cluster at the Brandix garment factory in Minuwangoda, 35 kilometres north-east of Colombo. By now, clearly, Covid-19 had got onto the island and wasn’t going away. Still, however, the situation seemed manageable. The island’s tropical climate helped. People could go out and gather in relatively safe outdoor spaces – for instance, restaurant terraces and gardens – at times of year when in other regions of the world they’d be forced into hazardous, crowded, badly-ventilated, virus-friendly spaces indoors by cold weather.

Unfortunately, on Sunday, April 18th, at the end of a holiday week celebrating the Buddhist and Tamil New Year in Sri Lanka, we realised things were going to take a serious turn for the worse. We went for dinner and a few drinks in a hotel bar we frequented. During our previous visits, the bar had been no more than 25 percent full, so that there was plenty of space for social distancing, and the punters were careful to wear masks whenever they left their tables. This Sunday night, however, the bar was mobbed, social distancing was non-existent and faces were unmasked as folk wandered from group to group. We lasted about two minutes there. Then, feeling extremely uncomfortable, we retreated to a sparsely populated restaurant in the same hotel. I suppose most of the clientele in the bar had just returned from their New Year holidays and were enjoying a final boozy night out before they went back to work.

In fact, the New Year festivities had been allowed to take place without any restrictions. People visited families and friends across the island and, the wealthier ones at least, crowded into the beach and mountain resorts as they would in any ordinary year. This had predictable consequences. As one journalist recalled, “cases began to rise rapidly, overwhelming the state’s mandatory quarantine care facilities. Soon, the intensive care units of a delicate hospital system were at full capacity. By May, hospitals were inundated.”

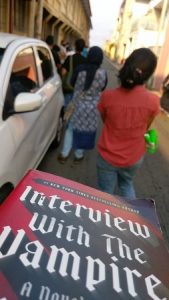

As I mentioned, May 25th was the last day when people could go outside, although strings had been attached to this ruling. Firstly, only one person per household was allowed to be out at any one time. Secondly, ‘vehicular’ movements were not permitted and you had to walk. This would presumably ensure that people visited only their local shops and strayed no more than a mile or two from home, thereby lessening risks of infection. I ventured out in the late morning, to get some money out of an ATM and then hopefully buy a few supplies in a non-mobbed supermarket.

When I emerged onto Galle Road, Colombo’s main thoroughfare, it was devoid of traffic and disconcertingly silent and still for a minute. Then a set of traffic lights behind me must have changed from red to green because I was passed by a small fleet of cars, tuk-tuks and motorcycles heading north towards the city centre. But after they’d gone by, silence prevailed for another minute. That was how things continued while I trekked along Galle Road to the ATM. Every so often there’d be brief spurts of traffic that the lights had accumulated and then released.

Only shops selling food or medicines were allowed to open today. Thus, there was activity around the little grocery / general-purpose shops that cluster near the entrance to Kathiresan Pillayar Temple on the eastern side of Galle Road in Colombo’s Bambalapitiya district. One shop-sign there I hadn’t noticed before was the luridly coloured one for the ‘Irissh’ Super – which sounds like it’s owned by an Irishman who slurs a bit when he’s had too much to drink. Further along, small queues of about half-a-dozen people waited to get inside the street’s pharmacies, like UniChemist, and mini-supermarkets, like Sathosa.

Having got cash from the ATM, I thought I would try the branch of Keells Supermarket on Marine Drive, which runs along the coast parallel to Galle Road. I have to say that by this time I was starting to suspect that not everyone was following the rules. As those knots of traffic passed me, I would notice the occasional middle-aged couple riding together on a motorbike, which made me wonder how strictly the police were enforcing the rule about only one member of each household being allowed out. Though perhaps what I was seeing on those motorbikes were two mature, but still horny, members of different households taking advantage of the situation to pursue an illicit love affair. Meanwhile, while I approached Keells, I noticed a suspicious number of cars pulling into its forecourt – this on a day when you weren’t supposed to travel by car. Still, the tuk-tuk drivers seemed to be toeing the line. The whole time I was outside, not one slowed and stopped and asked if I needed to go anywhere.

After seeing the small queues outside the minor supermarkets on Galle Road, I expected to have to wait for a time outside Keells, but I got in immediately. It was busy, but not too busy. The shelves and trays in the produce section had mostly been scoured clean, but there were reasonable stocks of everything else.

I carried my shopping home along Marine Drive, which was busier with traffic than Galle Road. The police stations of Colombo’s coastal districts, south of the city centre at least, are positioned along Galle Road and the drivers were probably using Marine Drive instead because they figured there was less chance of them being stopped and checked. However, Marine Drive’s pavements were practically deserted and the shops along its seafront were almost all shut. My local off-licence, the Walt and Row Association Wine Store, was shuttered – it was only food and medicine on sale today, strictly no booze. Similarly silent was the Westeern Hotel, the passageway leading to Harry’s Bar at the back of the premises sealed by doors with rusty metal bars. Actually, the nation’s pubs had been ordered to stop doing business as early as May 3rd.

It proved a melancholy walk and I couldn’t help but feel melancholy about the situation overall. Not just in Sri Lanka, where the authorities had taken their eye off the ball and a lot of people had acted selfishly and / or foolishly in April, resulting in this current crisis. In countries like India, Brazil and the USA – where ridiculous things have happened, like Republican politicians getting vaccinated on the quiet so as not to upset the brainlessly delusional anti-vaxxers who make up a large part of their support – arrogance, complacency and both wilful and genuine stupidity have resulted in massive Covid-19 spikes and huge but avoidable death-tolls. In Britain, despite a successful vaccination programme so far, there looks likely to be a third wave of infections while Boris Johnson’s hapless government dithers on whether or not to end Covid-19 restrictions later this month.

The sad thing is that the Covid-19 pandemic, serious though it is, doesn’t constitute the end of the world. However, manmade climate change is making itself felt in our lives now and threatens to transform the planet in ways that could be catastrophic to our civilisation later this century. If people generally, and politicians in particular, can’t get their act together to deal with Covid-19 in 2021, what hope is there for the decades ahead when we’ll really need to get our act together?