© Penguin Books

Daphne du Maurier’s 1941 novel Frenchman’s Creek comes nowhere near the standard of her best work. It lacks the growing unease, troubling ambiguity and general intensity of, say, Rebecca (1938) or My Cousin Rachel (1951). Even as a historical potboiler, it falls far short of Jamaica Inn (1936) because it doesn’t have a main character as monstrously memorable as Jamaica Inn’s villain, Joss Merlyn.

That said, with its twists and turns and skin-of-the-teeth escapes and rescues (predictable though they were), I found the book enjoyable as an undemanding romp. Also, its cultural politics seem amusingly ironic when viewed through the prism of 2024 Britain, insecure at home and diminished abroad after the fiasco of Brexit.

Frenchman’s Creek starts with its heroine Dona St Columb, basically a 17th-century desperate housewife, fleeing London for the wilds of Cornwall. Dona has been living it up in the capital with her doltish and drunken husband Harry and his circle of friends, but now she finds their company monotonous and shallow. Among them, only the smooth and confident Rockingham has much personality, but as he flirts aggressively with Dona behind her husband’s back and even enlists her help in perpetrating a cruel joke against an elderly Countess – they terrify the old dear one night by disguising themselves as highwaymen, stopping her coach and pretending to rob her – he’s obviously a bad ’un.

Thus, bored and disgusted, Dona leaves Harry behind and travels to his country estate on the Cornish coast, hoping to lead a quiet life. This doesn’t happen, of course. One of her landowner neighbours, Godolphin – who’s as oafish as her husband and suffers the additional disadvantages of having ‘bulbous eyes’ and a ‘growth on the end of his nose’ – informs her that the local countryside is in uproar, thanks to raids being carried out by a French pirate-ship, captained by a figure known only as ‘the Frenchman’. Meanwhile, Dona is puzzled to find the estate emptied of its servants, save for one enigmatic character called William, ‘with a button mouth and a curiously white face’, speaking with ‘a curious accent, at least she supposed it was Cornish’.

It soon transpires that William is in the employ of the Frenchman, and his ship La Mouette – The Seagull – is anchored within Harry’s estate, in a hidden creek off the side of an estuary. The pirates have been sneakily hiding there between their assaults on the neighbouring coastline. Dona falls into their clutches, but discovers that – quelle surprise! – the Frenchman, one Jean-Benoit Aubéry, is actually a dashing fellow. As well as having the requisite amounts of tallness, darkness and handsomeness, he wears ‘his own hair, as men used to do, instead of the ridiculous curled wigs that had become the fashion…’ (Needless to say, all the pompous Englishmen Dona knows wear wigs.) Even better, he has an artistic temperament – he loves drawing pictures – and he’s at one with nature – his pictures are of herons, sanderlings, herring-gulls and other birdlife.

Trusting Dona to keep her mouth shut, Jean-Benoit releases her from captivity. And before you know it, romance blossoms between the two of them. Not only is she inviting him up for dinner at her husband’s manor house, and he taking her on fishing expeditions, but she becomes a member of his crew. She’s on board La Mouette when it sallies forth from the creek, in search of booty. She even takes part in the raids on her neighbours’ coffers. Meanwhile, as one of the local gentry, Dona gets to hear all the plans Godolphin and his fellow landowners are hatching to trap and catch the Frenchman. The Englishmen never imagine that one of the supposedly silly, frivolous women in their company is secretly channeling this information to their enemy.

For a while, Dona lives the dream. She enjoys the charms of a hunky, creative and sensitive man and gets to participate in swashbuckling adventures. Then, however, Harry arrives from London to aid his neighbours in their efforts to apprehend the Frenchman – never suspecting that the naughty pirate is holed up in the nearby creek, right under his nose. Also, he brings Rockingham with him, and it’s his shrewd, caddish friend who begins to smell a rat…

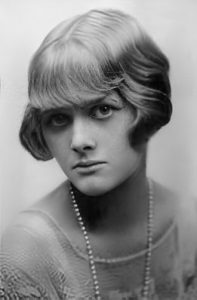

From wikipedia.org / © The Chichester Partnership

It’s fun to speculate on the audience de Maurier had in mind for this tosh. Frustrated 1940s English ladies, fantasizing about a hot-blooded continental man whisking them away from their humdrum middle-class lives? Especially, whisking them away from their repressed, pipe-smoking, cardigan-and-slipper-wearing husbands, chaps who probably found David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) a bit too raunchy?

Maybe she was trying to exploit an inferiority complex that lurks in the British psyche regarding the French. Well, in the English psyche – mention ‘France’ to Scottish people and many will simply enthuse about ‘The Auld Alliance’. There’s always been a feeling that compared to the average English bloke, the average French bloke is more suave, elegant, cultured and aware of what it takes to sweep les dames off their feet. (Mind you, the recent publicity surrounding the 20-stone horribleness that is Gerard Depardieu suggests that French male superiority in the charm stakes is just a myth.)

As a recent example of this Anglo-insecurity, when faced with Gallic masculinity, look at the anger with which Britain’s stupidest right-wing newspapers reacted to French president Emmanuel Macron turning up in London for Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral in 2022. Macron – of whom, I should say, I’m not usually a fan – wore sunglasses, a blue blazer and blue trainers and came accompanied by a phalanx of bodyguards who strutted with nonchalant Jean Reno-style coolness. He was accused of being disrespectful with his ‘casual’ attire, but come on… The real issue was cringing English jealousy. Compare Macron’s chicness with the appearance of former British prime minister Boris Johnson, who shambled to the funeral looking like a cross between an ambulatory compost heap and an electrocuted yeti.

No doubt this inferiority complex towards the French (and all things continental) has been compounded by the Brexit vote, which has left England / Britain on the fringes of Europe, looking rather daft and deluded.

Frenchman’s Creek was filmed in 1944, in a now-forgotten production whose one point of interest is that it was the only time Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce appeared together in a film that wasn’t a Sherlock Holmes adventure. It’d be interesting, though, to have the book filmed again in the 2020s. You could have some hot young French actor like Pio Marmaï or François Civil in the role of the Frenchman. Matt Lucas, channeling Boris Johnson, could be cast as Harry, Dona’s hapless husband; and Matt Smith – in psycho mode, rather than Doctor mode – cast as the alluring but nasty Rockingham. A range of bumbling and grotesque character-actors like Eddie Marson, Tom Hollander, Nick Frost and Reece Shearsmith could play Godolphin and the other English landowners.

I suspect desperate housewives all over Middle England would flock to see a new Frenchman’s Creek movie; even while ridiculous newspapers like the Daily Mail, Daily Express and Daily Telegraph fulminated at how it cast aspersions on the manliness of Dear Old Blighty.

Before I finish, I should mention that the pleasure you get from Frenchman’s Creek possibly depends on how much you can tolerate the character of Dona. I didn’t mind her, spoilt and self-centred though she obviously was, and just got on with enjoying the book’s narrative drive and historical colour. However, my partner – Mrs Blood and Porridge – also read the novel and detested it. This was due to Dona, whom she described as “insipid and childish… she’d marry a prisoner on death row because she’s rebelling against her oh-so-boring life… Meanwhile, people are starving and the bitch is f**king a murderer because it’s fun as long as she can luxuriate in her white upper-class ‘lady’ privileges. She’s an abomination. I hate her… her lack of a moral compass and her inability to imagine anything more for herself than a man.”

So, that’s me told, then.

© Paramount Pictures