© George H. Brown Productions / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

During the past fortnight I’ve wondered if I should post something about big, recent news stories. About, for example, the draw for next year’s FIFA World Cup in Canada, Mexico and the USA, which happened on December 5th and saw FIFA President Gianni Infantino present Donald Trump with something called the FIFA Peace Prize. Doing this, boldly going where no brown-noser has gone before, Infantino surely set a new record in how far a shameless groveller could wedge their head up Trump’s arse. Or about the cascade of claims by pupils at London’s Dulwich College in the 1970s that the young Nigel Farage was a dedicated follower of fascism, taunting Jewish schoolmates with comments like “Hitler was right” and telling black ones, “That’s the way back to Africa.”

But no. It’s Christmas-time. I don’t want to soil the festive atmosphere of good will by writing about revolting specimens of humanity like Infantino, Trump and Farage. So, instead, here’s a post about someone wholly wonderful and cherishable – Margaret Rutherford.

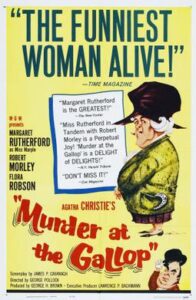

Wake Up Dead Man (2025), the new whodunnit written and directed by Rian Johnson, starring Daniel Craig as the gloriously accented Benoit Blanc, has just arrived on Netflix. The Blanc movies – which also include Knives Out (2019) and Glass Onion (2022) – are reminders of how entertaining whodunnits can be when done well. They put me in mind of an earlier series of cinematic whodunnits I find delightful and turn to whenever I need a comfort watch. These are the four Agatha Christie adaptations made in Britain in the early 1960s that have veteran English actress Margaret Rutherford playing Christie’s formidable, if elderly, crime-solver, Miss Jane Marple.

By then, Rutherford had become a national treasure in Britain for her comic roles in the theatre and cinema, for example, in stage and screen versions of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1939 and 1951 respectively) and Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit (1941 and 1945). The Miss Marple movies represent the last great hurrah of her career.

One aspect of the films I have a problem talking about is their faithfulness to the original novels. That’s because I’ve never read any of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple stories. Indeed, I’ve only read one Agatha Christie novel ever, 1932’s Peril at End House, which featured her other famous sleuth, the Belgian Hercule Poirot. However, having seen later versions of Miss Marple in TV adaptations where she was played by Joan Hickson, Geraldine McEwan and Julie McKenzie, it seems fair to say that the persona Rutherford invests the character with is not the persona Christie had in mind. Subsequent Marples have been quiet, focused and forensic, people you’d barely notice sitting in the corner of the drawing room while skullduggery was afoot. Rutherford’s Marple is a force of nature – you’d definitely notice her before long.

Christie was reportedly unhappy with the Rutherford movies, regarding them as comedies rather than the mystery stories she’d written originally. That’s true – they are comedies, very funny ones, rather than mysteries. But Christie seemed appreciative of Rutherford herself and even dedicated her 1963 novel The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side to her.

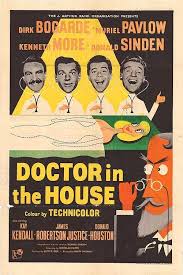

Though based on the works of a writer closely associated with the sub-genre known as the ‘country house mystery’, only one of the four Rutherford / Marple films mainly takes place in a country house. That’s the first one, 1961’s Murder She Said, based on Christie’s 1957 novel 4.50 from Paddington. Next up is Murder at the Gallop (1963), mostly set in a hotel run by an enthusiastic equestrian and foxhunter. It’s based on Christie’s book After the Funeral (1953), which actually featured Hercule Poirot. Murder Most Foul (1964), inspired by another Poirot novel, McGinty’s Dead (1952), is about murderous goings-on among the members of a theatre company. The same year’s Murder Ahoy! is almost an original screenplay, though it uses elements of the 1952 novel They Do It with Mirrors. Its story takes place on a former Royal Navy warship that’s become a floating reform school for juvenile criminals.

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

So, we’ve got a stately home, horse-riding, the theatre and the Royal Navy – four great British institutions. Accordingly, in the films, the heads of these four institutions are played by four much-loved British character actors of the period, James Robertson Justice, Robert Morley, Ron Moody and Lionel Jeffries respectively. Each is pompous and stuffy and when Rutherford’s Miss Marple arrives on the scene, determined to sniff out the rottenness in each institution – rottenness that’s led to murder – they aren’t happy. That’s largely what makes these movies enjoyable. We get to see some old-fashioned, patriarchal British pomposity being relentlessly pricked by an eccentric, infuriating old lady who refuses to know her place.

Indeed, I’d argue these movies are subversive in their quiet way. Rutherford’s Miss Marple is almost a forerunner to Columbo, the disheveled, blue-collar detective played by Peter Falk in the TV show of the same name (1971-78, 1989-2003). The murderers in that show are always rich, powerful bigshots who totally patronize and underestimate Columbo, but he manages to nab them in the end. Usually by mercilessly annoying them.

I’ve seen people – usually diehard Christie fans – criticise Rutherford’s portrayal of Miss Marple for being ‘dotty’ or ‘batty’, but she’s not that way at all. Rather, her Marple is admirably proactive. In Murder She Said, convinced the body of a woman she saw being strangled on a passing train is concealed somewhere on the premises of Ackenthorpe Hall, she infiltrates the mansion by taking on the job of its housekeeper. There, in the kitchen, she has to deploy all her culinary skills to feed the sizeable and demanding Ackenthorpe family. Meanwhile, she uses her enthusiasm for the game of golf as cover while she searches the grounds.

In Murder at the Gallop, she climbs on top of a cartload of beer-barrels so that she can peer through a top window and spy on the reading of a will. Later, she proves herself to be an accomplished horsewoman and she dances to some new-fangled rock-and-roll music. (“One must be tolerant of the young… I remember my dear mama was quite horrified when she caught me dancing the Charleston in public.”) Okay, she apparently incurs a heart attack while dancing, but that’s only a ruse designed to trick the murderer into giving away their identity. In Murder Most Foul she reveals herself as a past ladies’ pistol champion and, at the finale of Murder Ahoy!, as a fencing champion too. That’s before she takes on the villain in a swordfight – a sequence Rutherford spent a month training for.

So, a skilled cook, golfer, horse-rider, dancer, shooter and fencer – she might be light-years removed from Christie’s concept of her, but Rutherford’s Miss Marple is a shining example of, simultaneously, girl-power and grey-power.

Her feistiness even wins her the admiration of those pompous authority figures she’s spent the films irritating. At the end of Murder She Said, for instance, she gets a surprise when Luther Ackenthorpe, the irascible and bearish aristocrat played by James Robertson Justice, concludes that she’s just the woman to share his matrimonial bed. His proposal of marriage hardly drips with romance, though. “You’re a fair cook,” he tells her, “and you seem to have your wits about you and, well, I’ve decided to marry you.” Predictably, Miss Marple decides there are some things a girl has to say ‘no’ to – and this is one of them.

Another unexpected marriage proposal comes her way at the end of Murder at the Gallop, this time from Robert Morley’s horse-loving character Hector Enderby. Miss Marple isn’t taken by Enderby because he’s a keen foxhunter. “I disapprove of blood sports!” she tells him sternly. After she’s gone, Enderby sighs, “That was a very narrow escape.”

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

While Rutherford’s Miss Marple maintains her spinsterhood in these movies, the actress’s real-life husband, the actor Stringer Davis, has a prominent role in all four. At Rutherford’s insistence, the filmmakers invented a recurring character, ‘Mr. Stringer’, for him to play. No such character appears in the books. It could have been a disastrous piece of self-indulgence, but in the context of the films this addition works beautifully. Tweedy and timid, Mr. Stringer is the librarian in Miss Marple’s village. She turns to him when she needs research done or information dug up and he invariably, and unwillingly, gets drawn into her unorthodox investigations. He becomes a faint-hearted Dr. Watson to her gregarious Sherlock Holmes.

Davis and Rutherford dated for 15 years and didn’t tie the knot until 1945 when he was 46 and she 53. The delay was due to Davis’s mother, who deeply disapproved of Rutherford, and the couple only got married after she died. That might suggest Davis, intimidated by his mum, was as retiring as the character he plays in the films. But he was courageous enough to fight in both World Wars. During the first one, he served as a young officer at the front in 1918. At the start of the second one, he re-enlisted at the age of 40 and served for its duration. His World War II experiences included being evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940.

The films’ other recurring character is a genuine Agatha Christie creation who appears in four of her books. This is Inspector Craddock, played by Australian actor Charles ‘Bud’ Tingwell. Craddock starts each movie having his patience tested by Miss Marple’s meddling and wild claims but, of course, by the end of it, he’s reluctantly conceded she was right all along and is fighting her corner. A veteran of the Australian film industry, Tingwell moved to Britain in the 1950s. He’s forever etched in my memory as Alan Kent, the unfortunate traveller whose blood is used in a gory scene to revive Christopher Lee in the 1966 Hammer horror film Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966) – the first scary movie I saw that genuinely scared me. In the 1970s he returned to Australia, where his later films included the delightful and highly popular comedy The Castle (1997). By the time of his death in 2009, he was so respected that he received a state funeral in Melbourne.

© Lawrence P. Bachman Productions / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Meanwhile, the guest casts in these films are a joy for someone of my vintage and geographical background. They’re choc-a-bloc with faces familiar to me from watching TV as a kid – from either the 1960s and 1970s British TV shows or the 1950s and 1960s British movies that were broadcast then. As well as Robertson Justice, Morley, Moody and Jeffries, there’s Francesca Annis, James Bolam, Richard Briars, Peter Buttersworth, Andrew Cruickshank, Finlay Currie, Windsor Davies, Meg Jenkins, Arthur Kennedy, Duncan Lamont, Miles Malleson, Francis Matthews, William Mervyn, Derek Nimmo, Nicholas Parsons, Conrad Philips, Dennis Price, Flora Robson, Terry Scott, Robert Urquhart, James Villiers and Thorley Walters. Even a future Miss Marple, Joan Hickson, turns up in Murder She Said.

After Murder Ahoy!, Rutherford made one more appearance as Miss Marple. She and Stringer Davis appeared fleetingly in 1965’s The Alphabet Murders, a Hercule Poirot movie with Tony Randall playing the Belgian detective and none other than Robert Morley playing his sidekick, Hastings. I haven’t watched The Alphabet Murders, but it’s reportedly dreadful and Rutherford and Davis’s cameo may be the only good thing in it.

Admittedly, something that tinges my enjoyment of the Rutherford / Marple movies with a little sadness is knowing that a few years after making them Rutherford started to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease. Devoted to his wife, Stringer Davis cared for her until her death in 1972. He died himself just 15 months later.

Anyway, I shall finish here as it’s time to go and watch Wake Up Dead Man on Netflix. Hey, you know what? If that Daniel Craig plays his cards right, he could become the new Margaret Rutherford.

From wikipedia.org