From Old Enniskillen / © Neil P. Reid

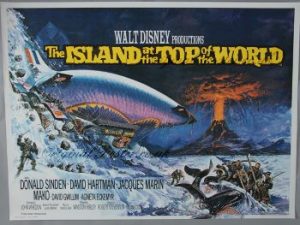

Two things inspired me to write this. Firstly, I recently discovered that the Ritz Cinema in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, began business in 1954, making 2024 the 70th anniversary of its opening. Secondly, I discovered that the Walt Disney live-action movie The Island at the Top of the World, the first film I saw in the Ritz or in any cinema, was released in 1974 – a half-century ago.

The Ritz was located on Enniskillen’s Forthill Street, next to the Railway Hotel and opposite and along from the local ‘mart’, as agricultural markets are called in Ireland. It struck me as a distinctive building during my visits to Enniskillen. I usually accompanied my mum on shopping trips, though she didn’t bring me to traipse around the shops with her. The town centre, with the main shops, was a control zone, which meant if you parked your car there you needed to leave someone sitting inside it. The 1970s were the most violent years of Northern Ireland’s Troubles, with the province’s retailing areas under threat from car-bombs. The security forces reasoned that if parked cars had people inside them, they were unlikely to be rigged to explode. So that was my function – to prove our car wouldn’t blow up while my mum was shopping.

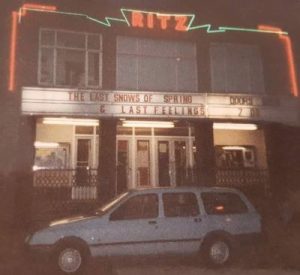

Anyway, the Ritz’s façade was a two-storey rectangle of red brick, with three archways at street level opening into a narrow veranda before the building’s entrance-doors, and with three big windows above. It was particularly striking when lit at night. Its upper half acquired an Art Deco-like frame of illuminated red and white neon, with the name ‘Ritz’ emblazoned in red capitals at the very top.

From an early age I was eager to get inside this mysterious and exotic-looking building, but there were problems. I lived in a village called Kilskeery that was nine miles from Enniskillen. To see a film in the Ritz one evening, I’d have to persuade my parents to make an 18-mile round-trip – or 36 miles if they took me, returned home and then went to collect me again when the film was done. And unfortunately my parents weren’t film enthusiasts. My mum had last gone to the ‘pictures’, as they were called in those days, to see a Tarzan movie. I suspect it’d been one of the late-1950s series starring Gordon Scott as the yodelling, loincloth-wearing, vine-swinging jungle man. My dad, meanwhile, never hinted at when he’d last been in a cinema. He didn’t call it going to the ‘pictures’ but to the ‘flicks’ – an even older term dating back to the 1920s, when silent, black-and-white films had flickered on the screens. So I assumed it’d been a long time ago indeed.

© Walt Disney Productions / Buena Vista Distribution

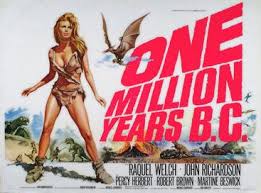

As I grew older and read the What’s On pages of the local newspaper, the Impartial Reporter, and saw the films that were showing at the Ritz, I waged a verbal war of attrition against my parents, begging them to let me go to the cinema to see such items as Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973), Disney’s animated version of Robin Hood (1973) and Roger Moore’s first Bond move, Live and Let Die (1973). Long before the Internet and YouTube, my only idea of what those films were like came from brief clips of them I’d seen on a kids’ TV quiz-show called Screen Test (1970-84), in which the contestants would watch excerpts from films, including newly-released ones, and then answer questions about them that tested their powers of observation and memory. The clips, predictably, were gathered from the films’ most exciting bits, which convinced me they were equally exciting for their entire running times and were thus the best things ever.

In the mid-1970s, having seen a bit of The Island at the Top of the World on Screen Test, and read in the newspaper that it was about to play at the Ritz, I resumed my pleading – and, finally, my parents gave in. Or rather, they talked my Uncle Robin into taking me to see it. I got what I wanted, and my parents didn’t have to go anywhere near the Ritz themselves, so it was a win-win solution. Except, of course, for Uncle Robin. My mother’s younger brother, Robin was a kindly and infinitely patient man, who usually got saddled with having to amuse and entertain the kids at family get-togethers. He had to listen to an immense amount of rubbish from me – I’d bombard him with questions like, “If Mytek the Mighty from the Valiant comic had a fight with the crew of the Seaview from Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, who would win?” (More than 30 years later, on the day of my mother’s funeral, I noticed my young niece and nephew instinctively making a beeline for him. Nothing’s changed, I thought.)

The fateful evening arrived. Uncle Robin escorted me into the Ritz and bought us tickets for balcony seats. And The Island at the Top of the World, a piece of undemanding hokum in which a crusty Englishman played by Donald Sinden charters an airship, travels to the North Pole in search of his missing explorer son, and discovers a lost world heated by volcanic activity and populated by Vikings, became the first film I ever saw in a cinema. Well, actually, it wasn’t the first film. No, that honour belongs to a documentary, whose title I don’t remember, about Ghana.

In the 1970s, going to the cinema in the United Kingdom – Northern Ireland was and still is a part of the UK, though a contested part – was an endurance test. The main film, the one you’d paid money to see, came at the end of what was innocuously called a ‘full supporting programme’. This programme usually consisted of a couple of tedious documentaries, travelogues or ‘experimental’ short films, ‘quota-quickies’ that were apparently made and shoehorned into cinema schedules as a way of keeping British filmmaking personnel in employment and keeping the British film industry alive. So, totally desperate to see some Donald-Sinden-in-an-airship-versus-Vikings action, I had to sit through a very dull documentary about modern-day Ghana. Then came a weird dialogue-free short film about two boys tormenting each other on the roof of a block of flats, which even my mild-mannered Uncle Robin, normally reluctant to criticise, said was a load of rubbish.

With all that out of the way, surely now Donald Sinden and his airship would be swooping up to the North Pole to take on those pesky Vikings. Right? Wrong. Presaged by the irritating, parping Pearl and Dean music, there followed a bunch of crackling, washed-out-looking commercials for eateries, car dealers and other businesses in Enniskillen – all, we were assured, just “yards from this cinema.” At some point too, the houselights came on and we were exhorted to go down to the front and buy some confectionary from the usherette. And furthermore, there were the trailers for forthcoming films to get through…

© Hammer Films / Shaw Brothers

In fact, for me, the trailers were one of the evening’s highlights. In 1970s Northern Ireland, at least, it was common practice for cinemas to show trailers for AA-rated (14 plus) and even X-rated (18 plus) movies before screenings of ones deemed suitable for all ages, like the Disney production we’d come to see. So, the Ritz aired a trailer for the Shaw Brothers / Hammer kung fu-horror film Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires, which was on the following week. In this, Count Dracula relocates to 19th century China and takes over a cult of Chinese vampires. Dracula’s old enemy Van Helsing and a team of local martial-arts experts have to hunt the bloodsuckers down. I thought this trailer was the best two-and-a-half minutes of celluloid I’d laid eyes on. I mean, kung fu fighting and vampires! When veteran horror star Peter Cushing shouted to martial arts expert David Chan, “Strike at their hearts!”, I wanted to punch my hand in the air and shout, “YES!”

Even after that, it still wasn’t time for The Island at the Top of the World. This was because Disney had released it as the second part of a double-bill, the first part being a 25-minute cartoon called Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too. But I found the Pooh cartoon entertaining. And then, at long last, Donald Sinden boarded his airship and flew to the Viking-infested North Pole. Like nearly all the films I saw in a cinema at an impressionable young age, I thought the movie was awesome – though no doubt if I watched Island now, it would seem a lot less good. (In the 50 years since, I’ve avoided watching it again for that reason.) I walked out of the Ritz that evening feeling exhilarated – though the stuff about Ghana and the weird kids on top of the block of flats left me feeling slightly bemused too.

My second visit to the cinema was to see the 1975 re-release of The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958), which featured monsters brought to life by the stop-motion-animation of special-effects wizard Ray Harryhausen. It was a lot easier to persuade my parents to let me go to this one. Noting that the Railway Hotel was next door to the Ritz, my Dad arranged to meet a farming mate (who’d done business earlier in the mart across the road) in the hotel bar. He dropped me at the cinema entrance, had a chat and a drink with his mate, and picked me up afterwards. In fact, Seventh Voyage was also part of a double-bill – the other half being the Italian comedy Watch Out, We’re Mad!, in which comic duo Bud Spencer and Terence Hill (real names Carlo Pedersoli and Mario Girotti) defended a funfair and its staff against some Mafia-type gangsters. This involved much comic fisticuffs and slapstick violence. It hardly constituted Kubrickian cinematic brilliance, but it seemed to my 10-year-old self the best movie ever. Also, though I’d watched Ray Harryhausen’s giant animated creatures on TV before, it was epic seeing them in Seventh Voyage on a big screen. So, I left the Ritz feeling well-satisfied that evening too.

© Morningside Productions / Columbia Pictures

© Columbia Pictures

To make things even better, the trailers that evening included ones for Norman Jewison’s essay in science-fictional sporting violence Rollerball (1975), and Gary Sherman’s cannibalistic-mutants-roaming-the-London-Underground horror classic Death Line (1972).

Another memorable Ritz visit came a year later when Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) surfaced at the cinema. For this, I was again entrusted to Uncle Robin. When we got there, we were astonished to see a queue snaking back from the entrance and along Forthill Street. “I’ve never seen a queue at the Ritz before!” marvelled my uncle. I had a sense that something seismic was happening – which was true, for Jaws marked the advent of huge, crowd-pleasing blockbusters and special-effects-laden franchises, plus the arrival of Spielberg, George Lucas and a generation of young filmmakers happy to give the public what they wanted, big-budget-style. It would eventually usher in the era of the multiplex cinema, which consigned the Ritz and similar small-scale cinemas to the dustbin, but more on that later.

Jaws was the first movie I saw in a cinema crammed to the bulwarks with people. Everyone was entranced by the events on the screen. As the communal sense of excitement heightened, their reactions became increasingly dramatic. And with Jaws, you had John Williams’ minimalist but brilliant theme music cranking up the audience’s feeling of apprehension and dread too: Duh… Duh! Duh… Duh! Duh, duh, duh, duh…

When the head of the unfortunate fisherman Ben Gardner dropped into view under his wrecked boat, squishily minus an eye, the auditorium filled with a whooshing noise that sounded like a great gust of wind – and then, all that breath inhaled, it was released again as a cacophony of screams. Later, when the shark popped his big face out of the water in front of the unsuspecting Chief Brody (Roy Scheider), prompting the famous quip, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” there was another chorus of screams – though this time tempered with laughter, because the moment was funny as well as scary. I know it has a lot to do with me being 11 years old at the time, but I can’t think of another cinematic experience in my life as exciting or visceral.

© Zanuck/Brown Company / Universal Pictures

My relationship with the Ritz ended soon afterwards, for in February 1977 my family moved from Northern Ireland to Scotland, settling close to the town of Peebles in the Scottish Borders. In fact, we lived only half-a-mile out of the town, and because Peebles High Street was home to a cinema called the Playhouse, I was suddenly able to see new films much more often. Tragically, this happy state of affairs lasted just seven months, for in September that same year the Playhouse closed down. After that, the nearest cinema – also called the Playhouse – was in the town of Penicuik ten miles north of Peebles. Hence, suddenly, my filmgoing situation became even worse than it’d been in Northern Ireland.

I occasionally returned to Northern Ireland to see relatives in the hinterlands of Enniskillen, so I got a few further opportunities to pop into the Ritz. For example, I remember going to see Marty Feldman‘s spoof of Foreign Legion movies, The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977). I mainly remember it because a woman sitting in the row behind me would erupt into ear-splittingly loud, hysterical laughter every time the bug-eyed Feldman – who suffered from Graves’ ophthalmopathy – appeared onscreen. That was very weird.

© Universal Pictures

During the 1970s and 1980s, TV ownership, then the invention of video cassettes and VCRs, and then the coming of multiplex cinemas – which started in 1985 with the opening of Milton Keynes’ ten-screen The Point – all contributed to the demise of small-town, single-screen cinemas in the UK. The Ritz lasted longer than most, not shutting its doors until 1992.

Remarkably, the building – pitifully boarded up – still stands. Or at least, it still did in 2022, which is when the image of it currently on Google Maps was taken. The also-derelict Railway Hotel next door, where my Dad hung out after he’d dropped me off to see The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, looks even more pitiful, closed off behind corrugated iron. They’re monuments – melancholy ones – to the days when taking a seat in a cinema auditorium seemed one of the most thrilling moments in my life.

And when I had Donald Sinden to look forward to, voyaging in an airship to the North Pole to take on Vikings, how could it not be thrilling?

© Walt Disney Productions / Buena Vista Distribution