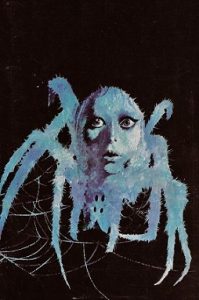

© Stygian Lepus

I grew up on a farm. In fact, I grew up on two farms, one in Northern Ireland and the other in Scotland. So when I write fiction, farms are a common setting for my stories. That includes scary stories, which I write under the pseudonym Jim Mountfield.

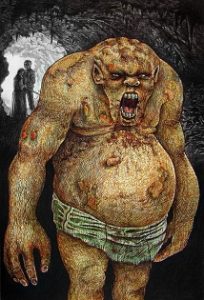

A big inspiration for my ‘farm-horror’ stories was a 2005 Irish film called Isolation, written and directed by Billy O’Brien. It’s about a lonely and financially-pressed farmer forced to take the filthy lucre of a bio-genetics company and let them experiment on his cattle. Being a horror film, this doesn’t result in faster-growing livestock as the company hopes but some nightmarishly malformed, slimy organisms whose alien tissue is soon infecting all living things on the farm, bovine and human. Though it’s not well-known, Infection has a great cast – including two of my favourite Irish actors, John Lynch and Ruth Negga, plus Essie Davis and Sean Harris.

What really impressed me, though, was its bleak agricultural setting, one where soulless concrete animal-sheds and black-tarped silage pits loomed next to decaying barns and lakes of slurry, everything dark and driech in the continuously pissing rain. This made me realise that, at least on a bad-weather day, much modern farming is so grim it’s a horror story even before any monsters show up.

© Film Four / Lions Gate Films / Irish Film Board

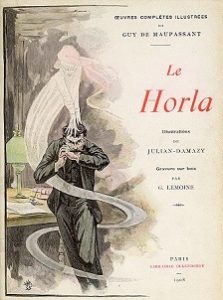

Last year, I had three farm-horror stories published – Wool in (the now sadly-defunct) The Sirens Call, The Turnip Thieves in Schlock! Webzine and The Shelter Belt in Witch House. Feeling I’d rather overdone this sub-genre, I didn’t write any more for a while. Until now – for I’ve just had a new, farm-set story published, one featuring the requisite soulless concrete sheds and decaying barns, rain and muck. It’s called Rack and Ruin and appears in the newly-published Issue 19 of The Stygian Lepus.

The original idea for Rack and Ruin came from the roadkill I’d frequently see on the back-road beside my family’s farm in Scotland. One very wet day, walking along that back-road, I encountered some roadkill that’d been so mashed by the wheels of passing cars, and partly-dispersed by the pounding rain, that I had no idea what animal it’d been. I gave the gruesome thing a wide birth as I walked by it. I would have given it an even wider berth if this had happened after I saw Isolation, for it resembled one of the squishy, hellish things in the film.

Rack and Ruin was also influenced slightly by the classic H.P. Lovecraft story, The Colour Out of Space (1927), in which a meteorite crashes in the hills of Massachusetts and releases a strange blight on the surrounding land – the property of a farmer called Nahum Gardner, who subsequently sees his crops and livestock mutate and become uneatable and unsellable and his family members die, disappear, go mad or grow horribly deformed. This is accompanied by the appearance of an indescribable colour that exists outside the visible spectrum.

Lovecraft’s story is told through the eyes of a narrator, a surveyor, who gets the details of the story from one of the Gardners’ neighbours. Thus, there’s little from the perspective of the farming family actually at the centre of the horror. I thought I would try to address this in Rack and Ruin. Farming is tough enough in the real world, being tethered to a piece of ground, toiling at it night and day in all weathers, trying to make a living from it whilst at the mercy of the natural climate and the economic one. Imagine how much worse you’d feel if your precious land was threatened by something inexplicably cosmic in origin.

The Colour Out of Space has been filmed several times and at least one of them, a 2019 version directed and co-written by Richard Stanley, does tell the story from the viewpoint of the Gardners. However, as Nathan Gardner – Stanley’s renamed Nahum Gardner – is played by Nicolas Cage, he hardly behaves like any farmer I’ve ever met. The scene where Cage freaks out after discovering his beloved tomatoes have been spoiled by the pesky meteorite is funny, though.

© SpectreVision / RLJE Films

For roughly the next month, my story Rack and Ruin can be read here. And for the contents page of The Stygian Lepus, Issue 19, and access to all its stories and articles, visit here.