From YouTube / © BBC

The great Scottish comic performer Stanley Baxter passed away earlier this month at the venerable age of 99. Newspaper obituaries for him noted that, though he was a bright star indeed in 1970s British television, by the late 1980s his star had seemingly vanished from the firmament. He’d gone. It was almost as if he hadn’t been there in the first place.

As a result, one obituarist wrote, it was unlikely that anybody under the age of 40 in modern Britain had heard of him. That does seem strange. I can remember his TV shows being, in their day, very big events. Over two decades, he only made six series – four of the Stanley Baxter Show between 1963 and 1971, one of the Stanley Baxter Picture Show in 1972 and one of the Stanley Baxter Series in 1981. But during the intervening years, he staged several lavish, one-off specials that kept his face in the public consciousness, especially in the 1970s. And his viewing figures were huge.

The reason Baxter himself gave for his abrupt disappearance during the 1980s was that his shows, full of song-and-dance extravaganzas and loving reproductions of old movie classics, became too expensive to make. In particular, the television executive John Birt – once described memorably by playwright Dennis Potter as a ‘croak-voiced Dalek’ – had a hand in pulling the plug on him. “It’s not that we don’t like your work,” he told Baxter. “It just all costs so much.”

It probably didn’t help that the type of entertainment Baxter was obviously smitten with, and slavishly reproduced and fondly parodied in his shows, had started to seem old-school by the 1980s. Much of his material was drawn from the black-and-white days of Hollywood and he clearly took pleasure of impersonating the likes of Marlene Dietrich or Shirley Temple. He also commonly referenced a former era of British cinema and theatre when accents were cut-glass and upper lips were stiff and he poked gentle fun at people like Sir John Gielgud and Noel Coward. But by the time of his later shows, the audience familiar with those reference points was surely ageing. A younger generation had arrived, more attuned to the 1970s New Hollywood movies of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola and the blockbusters of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Maybe Stanley Baxter’s TV career simply reached the end of its natural lifespan.

Incidentally, offscreen, Baxter was a quiet man who avoided publicity. This was partly due to the fact he was gay and for a long time he worried about the world finding out – sadly, he worried about this well after the point when most British people no longer gave a damn whether someone was gay or not. Anyway, by the 1980s, he was entering his sixties and probably welcomed retirement and being out of the public’s gaze.

I have to say, watching some of his sketches now, I find myself agreeing with a comment posted below one of the recent obituaries. The comment-writer said he thought much of Baxter’s TV work was ‘clever’ rather than ‘funny’. In fact, technically, those sketches are sometimes astonishing. Baxter played all the parts in them. However, because the digital compositing technology didn’t exist at the time to layer several images of him together in the same shot (and older techniques like multiple exposure and split-screen effect weren’t very convincing), the sketches were filmed from multiple camera angles with Baxter in different roles at different times. Copious use was made of filmed-from-behind body doubles and much editing was done afterwards. They must have been meticulously planned and taken ages to put together. No wonder, most years, we only saw him in a one-off special. Also, their writing was smart and Baxter’s impersonations were impeccable. But as far as comic value is concerned – well, I find myself smiling, perhaps chuckling, at them at best.

An example is his spoof of Upstairs Downstairs, the masters-and-servants-in-a-big-house costume drama that aired on British TV from 1971 to 1975 and was the Downton Abbey (2010-15) of its day. Baxter’s take on it is surprisingly meta. The servants downstairs are discussing how many of the toffs upstairs have been written out of the scripts recently and replaced by new characters played by bigger-name stars. Surely, they think, that can’t happen to them, since they’re all played by sturdy, salt-of-the-earth character actors? But it does – the punchline comes when housekeeper Mrs. Bridges is informed that she’s about to be replaced by Glenda Jackson. As usual, Baxter plays everyone during the eight-minute sketch and his impersonation of the starchy butler Mr. Hudson (in the real Upstairs Downstairs played by Baxter’s fellow Scot Gordon Jackson) is absolutely spot-on. But while I might be full of admiration by the end of it, I haven’t done much laughing during it.

In his sketches, Baxter plays women as well as men and his female impersonations are frequently great. British comedy has a long tradition of men dressing up as women: the Carry On movies (1958-92), Monty Python (1969-74), The League of Gentlemen (1999-2002, 2017), Little Britain (2003-6), Dick Emery, Benny Hill, Les Dawson and practically every pantomime ever. But those drag acts were invariably grotesque, their grotesqueness designed to provoke laughter. Baxter, though, delights in making his female characters as believable and, well, feminine, as possible. The novelist and critic Anne Billson responded to Baxter’s death the other day by observing how she now can’t watch Barbra Streisand singing Don’t Rain on My Parade in Funny Girl (1968) without thinking of Baxter impersonating Streisand and singing that song on one of his shows. I have no doubt that Baxter as Streisand was awesome.

For me, Stanley Baxter’s work was funnier when it left the showbiz world behind and focused on other things – especially things inspired by his Scottish roots. I fondly remember a sketch from one of his last specials, in the mid-1980s, wherein a strict Free Presbyterian clergyman (played by mighty character actor Andrew Keir) in the Scottish islands is enraged to hear sounds of partying coming from a house. It’s Sunday – the Sabbath. When he confronts the little old lady (Baxter) living in the house, she pertly informs him, “Oh, but we’re not dancing. We’re having an orgy.” She then describes a game being played inside. “The men-folk take all their clothes off and stand in a long line… The women are blindfolded and they have to identify the men by touch.” She invites the clergyman in, saying, “As a matter of fact, your name has come up twice.”

Also Scottish were perhaps his greatest achievements, the Parliamo Glasgow sketches, filmed in the manner of TV language-learning programmes of the time. The characters perform a skit in the target language, then change to English and inform the viewers about some of the useful words and phrases they’ve just heard. This being a Stanley Baxter piss-take, however, the target language is Glaswegian and the skits involve such expressions as “Thatzum bahookey yu-voan-yu” or, fabulously, “Zarra marra oanra barra, Clarra?” When the instructors switch to English, it’s in the ridiculously posh tones of Received Pronunciation (then a requirement for British TV presenters): “Again, an amorous young lady might use the word romantically to her bashful lover – ‘Zarra bestye kindae?’”

This fascination with language, dialect and accent informs another Baxter sketch, involving Nationwide (1969-83), the current affairs TV show broadcast on weekday evenings that consisted of reports from the BBC’s newsrooms across the regions and nations of the United Kingdom. The joke is that each presenter in each newsroom, in Belfast, Leeds, Cardiff and so on, speaks the local dialect there so strongly that nobody else can understand them. Finally, the programme switches to the main newsroom in London – where its presenter speaks with such exaggerated Received Pronunciation that he’s unintelligible too.

Though his television fame faded elsewhere in Britain, Baxter remained a name in Scotland. Throughout his career he’d appeared in Scottish pantomimes and in the 1980s and early 1990s he starred in a number of productions at Glasgow’s King’s Theatre: Cinderella (1980-81), Mother Goose (1983-84), Aladdin (1986-87) and, again, Cinderella (1991-92). I remember that last production getting much attention in the Scottish press because it was billed as his farewell to the stage. His pantomime work was often done in tandem with another Scot, Angus Lennie, who was best known for playing Steve McQueen’s sidekick, the ill-fated Archibald Ives, in The Great Escape (1962). Baxter and Lennie’s performances as the Ugly Stepsisters in Cinderella are legendary.

From YouTube / © BBC

He also turned up in Fitba, a 1990 episode of the Scottish TV sitcom Rab C. Nesbitt (1988-99, 2008-14). Here, he plays an elderly man, at death’s door, who’s a football fan. He’s so determined to see the Scottish men’s football team perform in the 1990 World Cup before he passes that he pays the titular character, the garrulous though rough-and-tumble Rab C. Nesbitt, to take him to the country hosting the tournament, Italy. Baxter’s character is decrepit and moribund and Rab is understandably sceptical about the undertaking. But he gradually wins Rab’s respect with his determination to make the most of what he has left. “My time is precious,” he tells Rab in Rome. “I’m taking a taxi into town. Then I’ll walk to Via Garibaldi and into Palazzo Doria Tursi to see, among other treasures, Paganini’s violin.” When he asks about Rab’s plans that afternoon, and is told he’ll maybe get a pizza, he retorts, “A pizza? In Italy? My, you’re full of ideas!” Thanks to Scotland’s recent qualification for the 2026 World Cup in North America, I was thinking about this episode and Stanley Baxter just a few days before he died.

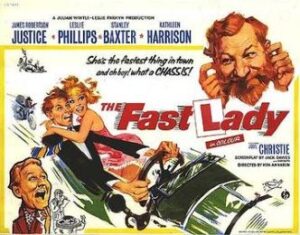

Finally, he featured in a handful of movies too: Geordie (1955), Very Important Person (1961), The Fast Lady (1962), Crooks Anonymous (1962) and Father Came Too! (1963). Decades later, he was one of the many people (also including Vincent Price, Donald Pleasance, Anthony Quayle, Joan Sims, Kenneth Williams, George Melly and Joss Ackland) who did voice-work for Richard Williams’ legendary, but never properly finished, animated epic The Thief and the Cobbler (1993).

As a kid, I loved The Fast Lady, though I daresay I’d find it juvenile and knockabout if I saw it today. But what a sublime cast it has – Baxter as the bumbling hero, Julie Christie as the woman he’s in love with, James Robertson Justice as Christie’s irascible and deeply disapproving father, and Leslie Philips as Baxter’s smooth best friend who tries to aid him in his love-life but only makes matters worse.

Ah, it makes me nostalgic. Who would you get in a British comedy film nowadays? Danny bloody Dyer – if you’re lucky.

© Independent Artists / Rank Organisation / Continental Distributing