Donald Trump has been inaugurated as 47th President of the United States of America. With social-media platforms like X, Facebook, Instagram, Threads and now TikTok acting as his cheerleaders and fascists like the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, Three Percenters and those deranged January 6th rioters he’s just pardoned acting as his law enforcers, he looks set to transform the USA into a combination of Vladimir Putin’s Russia, Ben Ali’s Tunisia and Benito Mussolini’s Italy. That’s while his administration abandons science and embraces paranoid conspiracy fantasies, superstition and stupidity, pumps umpteen more billions of tons of carbon into our already-poisoned biosphere, and conspires to destroy what democracies remain in the modern world. Therefore, it can be said we are now living in hell.

With these hellish things happening, I thought it would be appropriate to devote a blogpost to the most vivid representation of hell I have ever seen: that at Haw Par Villa, Singapore’s most remarkable museum.

Haw Par Villa was originally built by Burmese-Chinese brothers Aw Boon Haw and Aw Boon Par, who developed and marketed the famous analgesic remedy Tiger Balm. They relocated from Burma to Singapore in 1926 and purchased the site – today on the West Coast Highway, just along from the Haw Par Villa MRT Station – in 1935. The villa was designed in an Art Deco style and completed in 1937, but its original incarnation didn’t last long, being bombed and occupied by the Japanese during World War II and demolished after the war ended. Its gardens survived, though. Up to his death in 1954, Aw Boon Haw installed statues and dioramas there that he hoped would help instil ‘traditional Chinese values’ in those who viewed them. Subsequently, the gardens became a public park popular among Singaporean families.

By the 1980s, the place was losing its lustre and efforts to repackage it meant it underwent several name changes – from ‘Tiger Balm Gardens’ to ‘Haw Par Villa Dragon World’, back to ‘Tiger Balm Gardens’ and finally to ‘Haw Par Villa’ as it is today. No doubt the Singaporean Tourist Board understood it was special, thanks to those installations Aw Boon Haw had made to promote his vision. Yet it surely seemed too traditional, and too eccentric, to compete with the city-state’s more modern visitor attractions. A study in 2014 reported ‘low tourist interest’ in it and made the melancholy observation that it was ‘rather rundown and not very well maintained’. However, Journeys Pte Ltd acquired it in 2015 and closed it for a period at the start of the 2020s to make renovations. Since reopening, the latest version of Har Par Villa has won acclaim. In 2023, for instance, it was a finalist in the Singaporean Tourism Awards for Outstanding Attraction. Let’s hope its future is now secure.

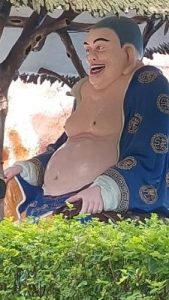

A while back, accompanied by my partner and a couple of friends, I visited Har Par Villa. Approaching its entrance, we went past the place’s name in blood-red English letters and Chinese characters raised against a tableau of artificial rocks. Then we went through a traditional Chinese paifang with a prominently-displayed picture of a tiger – appropriately for the home of Tiger Balm – and then found ourselves passing a gamut of strange statues. These included big, spooky white rabbits with red mouths and eyes, mad-looking sheep with black horns and black-rimmed eyes, and a freaky humanoid pig in britches, cap and shirt, the shirt peeled back to reveal a fat belly and sagging man-boobs. A couple with human bodies and tiger heads, wearing dungarees and a pink dress, held forward tins, boxes and packets of Tiger Balm. And a pot-bellied Buddha with a wide cackling mouth resembled one of the Blue Meanies in the animated Beatles movie Yellow Submarine (1968). It was all wonderfully, charmingly weird.

Our intention today was to visit just one part of Haw Par Villa, its most famous part – the attraction announced by a banner at the entrance, which said: ‘Hell’s Museum: Visions of Death and the Afterlife’. From all accounts, there’s much more to see there, but that would have to wait until another visit.

After buying tickets at the ticket desk / gift shop – whose door had a sign saying ‘No food, no drinks, no pets (pets go to heaven)’ – we ventured into the first section of Hell’s Museum. We discovered a corner where we could stand by a backdrop of red-hot lava, orange flames and grey smoke and have photos taken so that it looked like we were in hell; and a room where a short documentary film about religious concepts of death and hell played on a loop. Thereafter, we entered a modern and reasonably sober museum. Haw Par Villa is famous for some over-the-top, properly hellish depictions of hell, but those would come later.

The museum contained displays and charts giving information on such things as different cultures’ and religions’ beliefs in the afterlife, the history of ‘handling death’ in Singapore, ‘Singapore’s industry of cremation’ and, courtesy of a large map, the locations of all the cemeteries in the city-state – Chinese, Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Baha’i, Parsi, Burmese, Japanese and ‘War’. Among many other things, there were verses on the subject of death and hell from various sacred texts, such as the Buddhist Dhammapada. (Chapter 9, Verses 126-128: “Some are born in the womb; the wicked are born in hell…”)

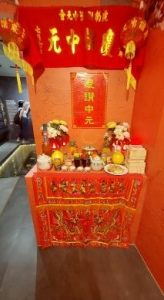

I particularly liked a replica of a Mexican Day of the Dead altar with all the traditional paraphernalia: photographs of the deceased, butterflies, flowers, bunting, candles, water, food, alcohol, cigars, salt, incense, mirrors, crosses and little skulls made of glass, ceramics, plaster and sugar. There was also one of ‘a traditional Chinese void deck funeral’. Void decks are the ground floors of the Singaporean Housing Development Board (HDB) apartment blocks that rise all over the city-state. These floors are normally untenanted and have communal spaces and, according to the museum, create ‘opportunities for residents to interact and bond over activities…’ and let them ‘…stage social functions, weddings, and of course funerals.’ Coincidentally, I’d lately read a short story entitled The Moral Support of Presence by the Singaporean writer Karen Kwek, about a woman having to organise and sit through a void-deck funeral for her mother whilst coping with grief.

Immediately past the modern museum was another area of Haw Par Villa eccentricity. The dioramas here included a mass of rock whose multiple folds and clefts were adorned with severed heads, their faces ghostly pale, tongues protruding, mouths and eyes leaking blood. An even more bizarre display was a rocky landscape where rats and rabbits were depicted at war with each other. I don’t know what story or legend inspired this, but to my Western eyes it resembled the title creatures of James Herbert’s The Rats (1974) taking on the rabbits in Richard Adams’ Watership Down (1972) – after those rabbits were infected with rabies. One rabbit chomping bloodily on a rat’s neck was an especially nasty detail. Meanwhile, I felt sorry for a pair of rats wearing medic armbands who were trying to carry away an injured comrade on a stretcher.

Finally we came to a structure housing Haw Par Villa’s most celebrated attraction – a series of dioramas representing the Ten Courts of Hell of Chinese mythology and Buddhism. Guarding its entrance were the demons Ox Head (a minotaur holding a trident) and Horse Face (an equine-headed being clutching a spiked club). These guardians, an information panel explained, were “…part of the netherworld’s bureaucracy. They form a network of attendants and jailers responsible for escorting souls through the ten courts…”

Inside, things started fairly innocuously with Court 1, where ‘King Qinguang conducts a preliminary trial for the deceased.’ The diorama here showed a recently-deceased soul cowering in front of King Qinguang while demon guards with superlong tongues and bird’s claws, or heads shaped like malformed gourds, looked on. Having been assessed according to the deeds they did alive, with the help of such judging tools as ‘the Book of Good and Evil’, ‘the Scale of Good and Evil’ and ‘the Mirror of Souls’, the souls are divided up: “Virtuous souls… may cross the Golden or Silver Bridges to either attain the Tao, become immortals or deities, or be reborn as humans blessed with good lives…”, whereas “…sinners will have to go through further judgement and punishment in the rest of the 10 courts.” Needless to say, it’s the ordeals of that latter group that gives this attraction its ghoulish zest.

Thereafter, we learnt what types of miscreants are dealt with in Courts 2-9 and what punishments are meted out to them. In Court 2, for instance, people who’ve caused hurt, cheated or robbed get ‘thrown into a volcanic pit’, those who’ve indulged in corruption, stealing or robbery (again) get ‘thrown into blocks of ice’, and those sullied by prostitution get ‘thrown into a pool of blood’. By Court 9, robbers, murderers, rapists and those responsible for ‘any other unlawful conduct’ have their ‘head and arms chopped off’ while anyone guilty of ‘neglecting the old and the young’ gets ‘crushed under boulders’.

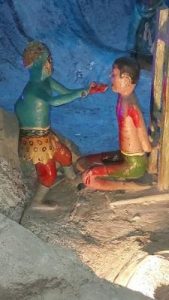

And the dioramas showed the courts’ demonic bureaucrats carrying out those punishments in bloody, gory detail. We saw hearts being extracted (as punishment for ungratefulness, being disrespectful towards one’s elders or ‘escaping from prison’); writhing bodies disappearing under giant grindstones (that’s what you get if you’re disobedient to your siblings or don’t show enough ‘filial piety’); folk being graphically impaled on the branches of ‘a tree of knives’ (your comeuppance for cheating, kidnapping or using bad language); and tongues being removed (the price you pay if you spread rumours or cause discord among your family members).

Fabulously, the chopping, severing, gouging, crushing, impaling, disembowelling, dismembering and decapitating going on in Haw Par Villa’s 10 Courts of Hell have encouraged generations of parents to bring their children here in order to instil moral values in them – or, putting it more bluntly, to terrify them into being good. They’ve forced their offspring to look on these horrors while warning them, “See what happens if you’re naughty!” Indeed, one of my Singaporean colleagues told me she was brought here when she was eight years old and suffered nightmares for the next fortnight.

I found myself wondering, meanwhile, what chastisements the 47th President of the USA would face when he passed away and entered the netherworld. From what I knew of his misdeeds, I calculated he’d be thrown into a volcanic pit, into blocks of ice, into a tree of knives and into a wok of boiling oil; have his heart and tongue cut out and his head and arms chopped off; and be grilled alive on a red-hot copper pillar, sawn in half and pounded by a stone mallet. Oh, and dismembered.

Lastly, in Court 10, we saw King Zhuanlun making a final judgement on the souls who’ve been through hell’s punishments, deciding “what forms they will take upon their rebirth. This will depend on their karma – the good and bad deeds committed in life.” In this diorama, there were two sinners on their hands and knees before the king, and already the animals they’d become in their next lives were taking form on their backs. One was metamorphosising into a black goat, the other into a white rabbit. Before being reincarnated as those creatures, they had one more port of call – ‘Meng Po’s Pavillion’, where their memories of previous lives, and presumably of hell, are erased.

With all this glorious, phantasmagorical barminess on display, it doesn’t surprise me that the Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka, who worked in Singapore at various times between 2014 and 2020 and whose Booker Prize-winning novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (2022) is about ghosts, demons and the afterlife in late-1980s Colombo, cites Har Par Villa as one of Seven Moons’ major inspirations.

As I’ve said, there was a great deal more at Haw Par Villa we didn’t have time to see that day. I can’t wait for our next visit to this splendidly baroque place.