© British Lion Films

The British actor Sir Christopher Lee, who was born on this day exactly 100 years ago, was a man who embodied evil to generations of film-goers. He played Lord Summerisle, Dracula, Fu Manchu, Rasputin, Scaramanga, Comte de Rochefort, Frankenstein’s monster, the mummy, Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Blind Pew, Saruman, Count Dooku, the Jabberwocky, the Devil and, in the 2008 adaptation of Terry Pratchett’s The Colour of Magic, Death himself. But up until his passing in 2015, I didn’t so much regard him as the embodiment of evil as one of the coolest people on the planet.

Lee did a lot during his 93 years and not just in terms of acting – though his movie resume was awesome, with some 275 titles to his name by the time he entered his tenth decade.

He was, incidentally, an incredibly literary actor too, because his massive film and television CV contained adaptations of stories by Lewis Carroll, Agatha Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Roald Dahl, Alexandre Dumas, Rider Haggard, Washington Irving, H.P. Lovecraft, Mervyn Peake, Edgar Allan Poe, Sax Rohmer, Sir Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Robert Louis Stevenson, Bram Stoker and Jules Verne. In real life, he was step-cousin of James Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming; and by the time Peter Jackson got around to filming the Lord of the Rings trilogy (2002-2004), he could boast that he was the only member of the movies’ cast and crew who’d actually met J.R.R. Tolkien. He was also good friends with Robert Bloch, author of Psycho (1959), the fabulous Ray Bradbury, and posh occult-thriller-writer Dennis Wheatley, whose potboiler The Devil Rides Out Lee would persuade Hammer Films to adapt to celluloid in 1968. And he was one of the last people alive who could claim to have met M.R. James, the greatest ghost story writer in English literature. As a lad Lee encountered James, who was then Provost of Eton College, when his family tried, unsuccessfully, to enrol him there. Lee obviously didn’t hold his failure to get into Eton against James because in 2000 he played the writer in the BBC miniseries Ghost Stories for Christmas.

Before getting into acting in the late 1940s, Lee did military service during World War II, which included attachments with the Special Operations Executive and the Long Range Desert Patrol , the forerunner to the SAS. He kept schtum about what he actually did with them. Decades later, though, he may have unintentionally dropped a hint about his secret wartime activities to Peter Jackson when, on set, he discreetly advised the Kiwi director about the sound a dying man would really make if he’d just had a knife planted in his back.

His first years as an actor did not see much success, due to his being too tall (six-foot-four) and too foreign-looking (he had Italian ancestry). During this period he at least learned how to swordfight, a skill he drew on when appearing in various low-budget swashbucklers. During the making of one such film, 1955’s The Dark Avenger, the famously sozzled Errol Flynn nearly hacked off Lee’s little finger; although later Lee got revenge when, during a TV shoot with the same actor, a slightly-misaimed sword-thrust knocked off Flynn’s toupee, much to the Hollywood star’s mortification and no doubt to everyone else’s amusement. Incidentally, I love the fact that Lee could boast of being the only actor in history who’d conducted sword fights with Errol Flynn and Yoda.

© 20th Century Fox

And I’ve read somewhere that when he made the swashbuckler The Scarlet Blade for Hammer Films in 1963, Lee taught a young Oliver Reed the basics of sword-fighting. I’m sure fight-choreographer William Hobbs and the stunt crew who worked on The Three Musketeers a decade later quietly cursed Lee for this. (Lee starred alongside Reed in the film, playing the memorably eye-patched Comte de Rochefort.) From all accounts, the ever-enthusiastic Ollie threw himself into the Musketeers’ sword-fights like a whirling dervish, and eventually one stuntman had to ‘accidentally’ stab him in the hand and put him out of action before he killed someone.

In 1956 and 1957 Lee got two gigs for Hammer films that’d change his fortunes and make him a star – playing the monster in The Curse of Frankenstein and then, on the strength of that, Bram Stoker’s famous vampire count in Dracula. Apparently, Hammer wanted originally to hire the hulking comedic actor Bernard Bresslaw to play Frankenstein’s monster. I suppose there’s a parallel universe out there somewhere where Bresslaw actually got the job; so that the man we know as Little Heap in Carry On Cowboy (1965), Bernie Lugg in Carry On Camping (1969) and Peter Potter in Carry On Girls (1973) went on in that universe to play Count Dooku in the Star Wars movies and Saruman the White in the Lord of the Rings ones.

Playing Baron Frankenstein in The Curse of Frankenstein and Van Helsing in Dracula was the legendary Peter Cushing and he and Lee would hit it off immediately, become best mates and make another 18 films together, in which for much of the time they did bad things to each other. As a mad-scientist-cum-asylum-keeper in The Creeping Flesh (1972), Lee brought a monster to life and then, after the monster had attacked Cushing and driven him insane with terror, he coolly incarcerated Cushing in his asylum. Whereas in The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973) Cushing chased him, as Dracula, through a prickly hawthorn bush – hawthorns are apparently harmful to vampires and the experience, Lee recalled in his autobiography Tall, Dark and Gruesome (1977), left him ‘shedding genuine Lee blood like a garden sprinkler’ – before impaling him on a sharp, uprooted fence-post. Meanwhile, the 1972 British-Spanish movie Horror Express featured a decomposing ape-man fossil that’d come back to life, was possessed by an alien force and had the power to suck people’s brains out through their eyeballs. It was such an evil motherf***er that Lee and Cushing had to join forces, for once, to defeat it.

© Granada Films

Lee was famously uncomfortable about being branded a horror-movie star and about being associated with Dracula, an association that might thwart his ambitions for a serious acting career. He did, though, play the character another six times for Hammer, and an eighth time in the Spanish production El Conde Dracula. Tweeting a tribute to him when he passed away, Stephen King said, “He was the King of the Vampires.” So sorry, Sir Christopher, but when the man who wrote Salem’s Lot (1975) says you’re the King of the Vampires, you’re the King of the Vampires.

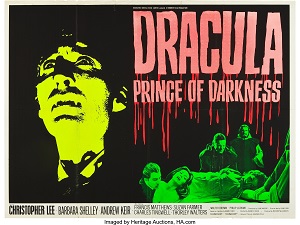

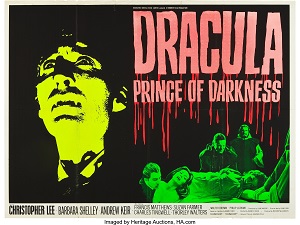

As Dracula, he got to bite Barbara Shelley, Barbara Ewing, Linda Hayden, Anouska Hempel, Marcia Hunt, Caroline Munro and Valerie Van Ost. Last-minute interventions by Peter Cushing in Dracula AD 1972 (1972) and The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973) prevented him from biting Stephanie Beacham and Joanna Lumley, which must have been frustrating. Meanwhile, the 1965 movie Dracula, Prince of Darkness was the first really scary horror movie I ever saw, on TV, back when I was eight or nine years old. I’d watched old horror films made by Universal Studios in the 1940s, like House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), in which everything was discreetly black-and-white and bloodless, so I wasn’t prepared for an early scene in Dracula, Prince of Darkness where Lee / the count is revived during a ceremony that involves a luckless traveller (Charles Tingwell) being suspended upside-down over a coffin and having his throat cut. The sight and sound of the blood splattering noisily onto the supposedly dead vampire’s ashes traumatised me.

© Warner Pathé / Hammer Films

Thanks to Hammer’s success in the horror genre, the late 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s saw a boom in British, usually gothic, horror filmmaking. And during that boom, Lee did many memorable, often evil, things. He drove his car into Michael Gough and squidged off Gough’s hand in Doctor Terror’s House of Horrors (1965). He forced Vincent Price to immerse himself in a vat of acid in Scream and Scream Again (1969). He turned up as a snobbish senior-civil-servant type and tormented Donald Pleasance in Deathline (1972).

Lee was probably Britain’s most linguistic actor, speaking German, French, Italian and Spanish and also knowing a bit of Swedish, Russian and Greek. Thus, he also found it easy to find employment making horror movies on mainland Europe, where the gothic tradition was raunchier, more lurid and looser in its plot logic than its counterpart in Britain. He worked with the Italian maestro Mario Bava in 1963’s The Whip and the Body and on several occasions with the fascinatingly prolific, but erratic, Spanish director Jess Franco. Despite Franco’s cheeky habit of shooting scenes with Lee and then inserting them into a totally different and usually pornographic movie – something Lee would only discover later, when he strolled past a blue-movie theatre in Soho and noticed that he was starring in something like Eugenie and the Story of her Journey into Perversion (1970) – Lee held the Spaniard in esteem and championed his work at a time it wasn’t fashionable to do so. Since his death in 2013, Franco’s reputation has improved and art-house director Peter Strickland’s movie The Duke of Burgundy (2014) is a tribute, in part, to him.

Franco directed the later entries in a series of movies about Fu Manchu that Lee made in the 1960s, in which he played Sax Rohmer’s supervillain in un-PC Oriental makeup and spent his time barking orders at Chinese minions, who were usually played by Burt Kwouk. As well as retaining some of the racism that was prominent in Rohmer’s books, the series generally wasn’t up to much in terms of quality. However, the film’s endings have always haunted me. Invariably, Fu Manchu’s secret headquarters would blow up and then Lee’s voice would boom imperiously through the smoke, “The world will hear of me again!”

© Eon Productions

In the early 1970s, Lee finally got opportunities to make the sort of films he wanted to make, including Richard Lester’s two Musketeers movies (1974 and 1975); the ninth official Bond movie The Man with the Golden Gun (1975), in which he taunted Roger Moore, “You work for peanuts – a hearty well-done from Her Majesty the Queen and a pittance of a pension. Apart from that, we are the same. To us, Mr Bond. We are the best… Oh come, come, Mr Bond. You get as much fulfilment out of killing as I do, so why don’t you admit it?”; and Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), regarded by many as the best attempt at bringing Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s deerstalker-wearing super-sleuth to the screen.

In that latter film, Lee played Holmes’s snooty brother Mycroft. Lee also played Sherlock Holmes himself several times, including in a couple of early-1990s TV movies with Dr Watson played by the impeccable Patrick Macnee, whom decades earlier had been Lee’s schoolmate at Summer Fields School in Oxford. And he played Henry Baskerville in the 1959 Hammer adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles, which had Peter Cushing in the role of Holmes. But for some strange reason, nobody ever thought of casting Lee as Professor Moriarty.

In 1973, he also played Lord Summerisle in The Wicker Man, a film that needs no introduction from me. Actually, next year is the film’s fiftieth anniversary. I trust the Scottish Tourist Board will celebrate this fact on May 1st, 2023, by lighting lots of wicker men, with lots of sanctimonious, virginal, Free Presbyterian policemen inside them, along the coasts of Scotland.

Later in the 1970s, no longer so typecast in horror movies and with the British film industry on its deathbed, Lee decamped to Hollywood. He ended up appearing in some big-budget puddings like dire 1977 disaster movie Airport 77 and Steven Spielberg’s supposed comedy 1941 (1979), but at least he was able to rub shoulders with icons such as Muhammad Ali and John Belushi. And he didn’t, strictly speaking, stop appearing in horror movies. He was in the likes of House of the Long Shadows (1982), The Howling II: Your Sister is a Werewolf (1985), The Funny Man (1994) and Talos the Mummy (1998). Amusingly, Lee usually explained this by arguing that these weren’t really horror films. The Howling II: Your Sister is a Werewolf wasn’t a horror film? Aye, right.

© New Line Cinema / WingNut Films

Though he never relented in his workload, it wasn’t until the 1990s that Lee experienced a late-term career renaissance – no doubt because many of the nerdish kids who’d sneaked into cinemas or stayed up late in front of the TV to watch his old horror movies had now grown up, become major players in the film industry and were only too happy to cast him in their movies: Joe Dante, John Landis, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Peter Jackson and Tim Burton. Hence his roles in two of the biggest franchises in cinematic history, the Star Wars and the Lord of the Rings / Hobbit ones, plus five movies directed by Burton.

When he was in his eighties, Lee must have wondered if there were any territories left for him to conquer – and he realised that yes, there was one. Heavy metal! He had a fine baritone singing voice but only occasionally in his film career, for example, in The Wicker Man and The Return of Captain Invincible (1983), did he get a chance to show it off. In the mid-noughties, however, he started recording with symphonic / power-metal bands Rhapsody of Fire and Manowar and soon after he was releasing his own metal albums such as Charlemagne: By the Sword and the Cross and Charlemagne: The Omens of Death, which had contributions by guitarist Hedras Ramos and Judas Priest’s Richie Faulkner. He also released two collections of Christmas songs, done heavy-metal style. The festive season will never seem the same after you’ve heard Lee thundering his way through The Little Drummer Boy with electric guitars caterwauling in the background.

© Charlemagne Productions Ltd

Obviously, the heavy metal community, which sees itself as a crowd of badasses, was flattered when the cinema’s supreme badass – Lord Summerisle, Dracula, Fu Manchu, Rasputin, etc. – elected to join them and they welcomed Lee with open arms. They even gave him, as the genre’s oldest practitioner, the Spirit of Metal Award at the Metal Hammer Golden Gods ceremony in 2010.

So: singing heavy metal, speaking eight languages, being perhaps the 20th century’s greatest screen villain and, probably, bayoneting Nazis to death. Was there anything this man couldn’t do? Well, it seems the only thing he couldn’t quite manage was to live forever. Mind you, for someone who spent his cinema career dying – even when he penned his autobiography in his mid-fifties, he reckoned he’d been killed onscreen more than any other actor in history – but kept coming back, it feels a bit odd to be writing about Christopher Lee in the past tense.

Actually, if anybody wants to congregate in a Carpathian castle after dark and perform a blood-soaked ritual to resurrect the great man, I’m up for it.

From the Independent