© Warner Bros / Proximity Media

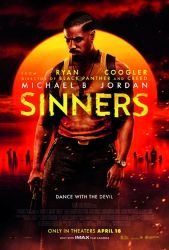

A few days ago my partner and I went to see Sinners, the new horror-cum-gangster film directed, written and co-produced by Ryan Coogler. Here are my thoughts on it. And before I go any further, a word of warning: there will be spoilers.

To be honest, I wasn’t expecting a great deal, as I’d heard something about its plot and it sounded horribly like 1996’s Robert Rodriguez-directed, Quentin Tarantino-scripted From Dusk till Dawn. Although a few misguided souls nowadays look back on that film as a neglected and misunderstood classic, I have to say I f**king hated it. In part, this was because From Dusk till Dawn began so well, as a nastily-effective little crime thriller wherein two fleeing bank-robbing brothers (Tarantino and George Clooney) kidnap a pastor (Harvey Keitel) and his family and force them to smuggle them over the US / Mexico border. Disappointingly, things then go south in all senses of the phrase. The group arrives at a mysterious Mexican bar called the Titty Twister where the staff and many of the patrons prove to be – surprise! – vampires. The rest of the film is a ludicrous, tongue-in-cheek splatterfest where the humans battle against waves of bloodsucking undead. While From Dusk Till Dawn’s sudden change of tone has been praised in some quarters for its audacity, I found it a vertiginous plunge into cheesy bollocks.

Anyway, the structure of Sinners is not dissimilar. Its first half plays out as a period gangster story, then vampires show up and its latter half becomes an exercise in horror. Set in the Mississippi Delta in 1932, it’s about the homecoming of black gangster twin brothers Stack and Smoke (both played by Michael B. Jordan) who’ve recently left Chicago where, it’s suggested, they worked for Al Capone. On their home turf, they embark on a new project – purchasing a disused sawmill and turning it into a juke joint, i.e.. a place for live music, dancing, drinking and gambling whose customers are from the local African American community.

To ensure the juke joint’s opening night is a success, they staff it with trusted friends, family members and associates: Smoke’s ex-wife, the occult-dabbling Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), and Chinese shopkeepers Grace (Li Jun Li) and Bo (Yao) to handle the catering; hulking buddy Cornbread (Omar Miller) to man the door; and boozy old bluesman Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo), slinky singer Pearline (Jayme Lawson) and young, startlingly-talented guitarist Sammie (Miles Caton) to provide the music.

© Warner Bros / Proximity Media

Despite a few obstacles – two thieves who soon regret tangling with the take-no-prisoners Stack, the fact that the sawmill’s former owner is head of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, and the disapproval of Sammie’s dad, a preacher who believes music is only virtuous if it’s used to further the word of the Lord – the juke joint opens, pulls in the crowds and is soon swinging. And then the vampires arrive.

Yes, I was dreading this moment – because I had really enjoyed the non-fantastical part of the film. Coogler did a great job depicting the minutiae of the 1932 Mississippi Delta. This was a world where the black population was just a couple of generations removed from the official slavery of the Confederacy and most of them now toiled in the racket that was sharecropping, a form of unofficial slavery. At the same time, they were crafting a musical culture, the blues, that would ultimately revolutionise American and global music through its influence on rock and roll. One touch among many that I liked here was the portrayal of the Chinese shopkeepers, Grace and Bo, who thanks to their ethnicity are able to run stores in both districts of the Mississippi town of Clarksdale, the black one and the white one.

Anyway, when the vampires show up, does the film turn to shite as From Dusk till Dawn did? Thankfully, no. Coogler provides some foreshadowing to prepare us for the twist, so it doesn’t come as a credibility-straining bolt from the blue. During the opening sequence, a voice-over talks about certain types of music being “so pure it can pierce the veil between life and death, past and future” and attract supernatural creatures – an idea that’s echoed later when the vampires admit Sammie’s miraculous guitar-playing has drawn them to the juke joint. (Even before the vampires arrive, Coogler treats us to a phantasmagorical sequence where Sammie’s playing seems to conjure up among the dancing crowd the spectres of music past and future – West African shamans, Chinese Xiqu performers, hip-hop DJs and an electric guitarist who looks like he’s a member of George Clinton’s P-Funk collective.)

Also preparing viewers for the tonal switch is an earlier sequence where a white man, Remmick (Jack O’Connell), flees from a squad of Choctaw Native Americans and takes refuge in a cabin inhabited by a hard-up white couple. The pursuing Native Americans politely warn the couple that they’re sheltering something evil. But as KKK robes are visible inside the cabin, it’s no surprise that the couple believe the story of their white visitor rather than that of the ‘Injuns’. Noticing the sun is setting, and with a shotgun pointed at them, the Choctaw decide discretion is the better part of valour and retreat. Which leaves Remmick to reveal himself as a vampire and infect his two saviours.

Coogler leaves this bit of world-building unexplored – which makes it wonderfully intriguing. Why are the Choctaw acting as vampire hunters? It also reminds me of the start of John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), where a dog – actually the titular thing in canine form – is chased by a pair of wrathful Norwegians in a helicopter. Compared to the Norwegians, though, the Native Americans are more pragmatic and level-headed.

© Warner Bros / Proximity Media

Later, Remmick and the vampirised Klan couple appear on the threshold of Smoke and Stack’s new juke joint, bearing musical instruments and pleading to be let in (“We heard tell of a party”) so that they can have a jamming session with Sammie. Sinners makes much of the belief that to get onto a premises, a vampire has to be invited – and Smoke and Stack, suspicious of white folks, are in no hurry to invite this trio inside. So they bide their time outside, biting and vampirising anyone who goes home early or nips out of the building for a pee. While they wait for their opportunity to get inside, their numbers grow…

In a smart move, Coogler makes Remmick Irish and gives him a taste for music as strong as his taste for blood. So, lurking outside, the vampires knock out a few tunes themselves – a charming version of the Irish / Scottish folk number Wild Mountain Thyme, for instance, and when there’s enough of them to stage a full-scale vampire hooley, a raucous rendition of Rocky Road to Dublin, during which Remmick indulges in some step-dancing. This makes being a vampire look like fun and Remmick, entreating the folks in the juke joint to surrender to him and his horde, makes a persuasive-sounding case for being vampirised. Once you’re a vampire, it doesn’t matter what skin-tone you have. Black vampires are treated no worse than white ones: “This world already left you for dead. I can save you from your fate. I am your way out.”

There’s a snag, of course. Remmick, as the Count Dracula / Mr. Barlow-style lead vampire, calls the shots and his minions have to do his bidding. Indeed, they seem parts of a giant hive-mind – evidenced by their chorused singing of Rocky Road to Dublin, which contrasts with the individuality Sammie expresses with his guitar. And Remmick’s interest in Sammie and his music isn’t motivated by an impulse of sharing but by a desire to assimilate them.

It’s fun to speculate who or what Remmick symbolizes. When he makes his first pitch at the juke joint’s door, begging to be let inside while Sammie, Delta Slim and Pearline perform, I was reminded of those white British rock-and-roll bands of the 1960s, like the Rolling Stones, the Animals and the Yardbirds. Influenced by the likes of Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, they started their careers desperate to play blues music and become known as bluesmen themselves. Which prompted Sonny Boy Williamson II to quip caustically: “These English boys want to play the blues real bad… And they do, real bad.”

But maybe it makes more sense to compare Remmick to the white-owned American music industry. His hunger for Sammie parallels how that industry gobbled up black artists, of blues, jazz, gospel, soul, funk, whatever, and made a fortune off their music whilst giving them as little credit, money and control over their work as possible. Often, their songs ended up being sung by someone else, someone white – see Pat Boone singing a version of Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti just five months after its release in 1955 – with precious few royalties making it their way.

Incidentally, late on, Remmick comes out with a sob story about how he was persecuted and deprived of his land in Ireland – presumably at the hands of the British and presumably back in the days when he was still human. That a victim of oppression has become a supernatural killing machine, one with a fascistic disregard for the lives of the people he feeds on, is Coogler’s way of reminding us that many poor white people, treated like dirt in their home countries, emigrated to other parts of the world where they treated indigenous people and black people like dirt too. It’s a sad reflection on human nature that people near the bottom of the pile have a psychological need to believe there are people even further down the pile whom they can mistreat and regard as inferior. Though this observation would no doubt delight Elon Musk, who recently grumbled that the “fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy”.

I’ve spent a lot of time analysing Sinners but I should also say it’s a supremely entertaining movie. It’s exciting, scary, funny and atmospheric. Furthermore, it proves a point that many filmmakers overlook – if you want a horror film to grip an audience, give them likeable and sympathetic characters to identify with. That way, they have an investment in those characters and things feel much more tense when bad stuff starts happening.

© Cedric Burnside Project

© Silvertone Records

It goes without saying that the soundtrack is great too. I’m particularly pleased to see that Cedric Burnside had a hand in performing some of the blues tunes – I attended a cool gig by Burnside at the Edinburgh Jazz and Blues Festival in 2015 and afterwards got his signature on a CD as a present for one of my mates. Also, don’t rush off when the credits start rolling at the end. There’s still a scene to come, one set in the early 1990s and featuring the venerable bluesman Buddy Guy. (By a coincidence I saw Guy perform in the early 1990s, though obviously the early-1990s Guy in Sinners is a good bit older than the one I witnessed.) It’s a coda that’s both sinister and affecting.

And the acting is excellent. Michael B. Jordan is impressive in the twin roles of Smoke and Stack. I soon forgot that both characters were being played by the same person. It’s a pleasure seeing Delroy Lindo again, whom I fondly remember as the villain in the 1995 adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s Get Shorty and from numerous Spike Lee movies. And as Sammie, Michael Caton is a revelation. He’s young and naïve, as the script demands, but he’s blessed with a deep, prematurely-old voice that totally persuades you this lad can sing and play the blues.

One thing about the casting, though. Jack O’Connell is perfectly fine as Remmick. But since the character is a scary old monster who’s Irish and musical, I don’t know why they didn’t cast the obvious candidate for the role: Van Morrison.

© Warner Bros / Proximity Media