© Merciful Release

When American music composer and producer Jim Steinman died last week, the tributes paid to him made heavy mention of two titles: 1977’s Bat Out of Hell, the album by Meat Loaf, and 1983’s Total Eclipse of the Heart, the ballad by Bonnie Tyler. Steinman wrote the songs, played keyboards and percussion and provided ‘lascivious effects’ on the former and wrote and produced the latter. He was not a man who did things by halves in his orchestrations, in his lyrics or in the performances he encouraged from his singers. Thus, both Bat and Eclipse are synonymous with bombast, histrionics, chest beating, garment rending, howling at the moon and general wildly over-the-top melodrama.

Which makes my experiences with Steinman’s two most famous pieces of work strange. Because when I hear Bat Out of Hell nowadays, the images that it conjures up in my head are of the summer landscapes of bucolic Country Tyrone in Northern Ireland: of hayfields, barley-fields and pastureland populated by herds of cattle and flocks of sheep. Whereas if I hear a burst of Total Eclipse of the Heart, I’m immediately transported to the wolds of equally bucolic County Lincolnshire in England, during the early springtime, with freshly ploughed fields undulating off into the soft morning mist.

To elaborate. In the summer of 1982 I worked on the farm of my Uncle Annett, in the Clogher Valley in County Tyrone. My cousin there was a big Meat Loaf fan and when we weren’t toiling in the fields and were back in the farmhouse, Bat Out of Hell never seemed to be off the stereo. The farmhouse reverberated with the vrooming of motorcycles and Meat Loaf hollering about screaming sirens, howling fires, evil in the air, thunder in the sky, being all revved up with nowhere to go, praying for the end of time, glowing like metal on the edge of a knife, etc. Stirring stuff, but it was incongruous background music for my life at the time, which consisted of lugging around bales of hay, mucking out cowsheds, feeding pigs, thinning turnips and holding down sheep while they had their fleeces sheared.

Admittedly, I did ride a motorbike that summer. My cousin had recently graduated from riding a motorbike to driving a car and his old motorcycle was stashed in an outhouse on the farm. My uncle took it out and taught me how to ride it. I didn’t venture out onto the roads, though. Instead, I’d ride it up the surrounding slopes and across the surrounding fields when I had to check on my uncle’s sheep. So no doubt while I cruised past those woolly flocks, Meat Loaf was roaring in my brain about hitting the highway like a battering ram on a silver-black phantom bike and so on.

© Sony / Epic / Cleveland International Records

Fast-forward eight months from then to March 1983 and I was employed in a different job in a different part of the world. I was working as a volunteer houseparent and classroom-assistant at a residential school for ‘maladjusted boys’, which was the un-politically correct 1980s parlance for what today would be termed ‘boys with behavioural issues’. The school was on the outskirts of the town of Louth in Lincolnshire, in the English Midlands. Walk one way from the school and you’d end up in the town, walk the other way and you’d soon be among the gently curving Lincolnshire wolds. The school’s older boys stayed in their own residence, with its own kitchen and living room, and I was doing an evening shift there one Thursday when Top of the Pops started on the living-room TV. The show aired a newly released song and video by Bonnie Tyler, Total Eclipse of the Heart.

The Lincolnshire lads in the residence were either sharp-footed Michael Jackson wannabes or bequiffed rockabilly types who’d been influenced by the Elvis albums in their dads’ record collections. Their immediate reaction, and my immediate reaction, was: “What the f**k are we listening to?” For Ms Tyler’s tonsil-rattling performance, caterwauling about falling in love, falling apart, living in a powder keg, giving off sparks, forever going to start tonight, etc., was unlike anything we’d heard before.

It was also unlike anything we’d seen before. The video, directed by Australian filmmaker Russell Mulcahy, and full of fluttering candles, billowing lace curtains, slow-motion flapping doves, dancing ninjas, nocturnal fencers, indoor American football players, acrobats in bondage gear and glowing-eyed demonically possessed choirboys, was pretty far-out too.

The song immediately went to number one in the British singles charts so I heard a lot of it in the ensuing weeks. In particular, it got played a lot in Louth’s top – only? – post-pub nightspot of the time, which was the social club for the local branch of the Liberal Party. Thus, while its dance floor quaked to the bellowing of Bonnie Tyler, I’d be sitting having a pint with some regulars who were proudly telling me for the umpteenth time how they’d ‘had David Steel in here just the other year.’

Today I don’t mind Bat Out of Hell too much, but I could happily live the rest of my life – and any future lives, if reincarnation is a thing – without ever hearing Total Eclipse of the Heart again. For one thing, Eclipse’s success spawned a zillion hideous 1980s and 1990s power ballads, sung under the misapprehension that the louder and shriller you are, the greater the emotion you convey. The biggest culprit here is Celine Dion and yes, it was Jim Steinman who penned her interminable 1996 ballad It’s All Coming Back to Me Now.

From jimsteinman.com

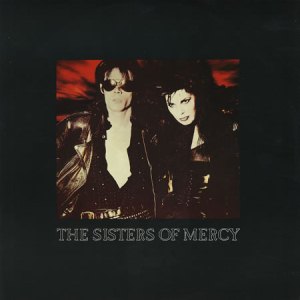

And yet… I can forgive Steinman for any crimes he indirectly committed against music by encouraging the growth of the power ballad. That’s because for a couple of years at the end of the 1980s he worked with the Goth-rock band the Sisters of Mercy and made them sound like the mightiest group in the universe. In 1990 he co-wrote and co-produced the storming tune More with the band’s frontman Andrew Eldritch, while in 1987 he produced two Sisters songs, Dominion / Mother Russia and This Corrosion. The latter is surely one of the greatest Goth anthems ever.

Although This Corrosion was written by Andrew Eldritch, it has Steinman’s aural fingerprints all over it, most notably the Wagnerian squalls of guitar and the use of the 40-strong New York Choral Society to provide a celestial choir at the beginning. Sweetly, the first comment below the song’s video on YouTube claims that “When a Goth dies, their voice gets added to the choir at the intro.”

Eldritch once told Sounds magazine that “It’s about the idiots, full of sound and fury, who stampede around this world signifying nothing… about people who sing about the corrosion of things while they themselves are falling apart.” Supposedly, the sound-and-fury-filled idiots he had in mind were his former colleagues Wayne Hussey and Craig Adams, who quit the Sisters of Mercy in 1985 and formed their own band the Mission. Elsewhere, in Q magazine, he likened the relationship between the Sisters of Mercy and the Mission to that between China and Taiwan. It was obvious which band Eldritch considered the equivalent of the massive, nuclear-armed superpower.

Now I like the Mission. However, in 1998, a 36-song compilation of 1980s and 1990s Goth, industrial, synth and dark indie music was put together under the title of Nocturnal and it had This Corrosion as its opening track and then the Mission’s song Deliverance as its second one. And when I heard the two played together, I realised that with their Steinman-produced opus the Sisters of Mercy blasted the Mission out of the water. Incidentally, This Corrosion is used to great effect in the finale of Edgar Wright’s underrated 2013 sci-fi / horror / comedy movie The World’s End.

Despite having a reputation for being a bit of a dick to work with, Eldritch spoke generously of Steinman. For instance, he said that Steinman “really knows how to make a wonderfully stupid record. Totally outrageous. Every time you think to yourself, do we really want to go this far, and you say to Jim, ‘Jim, are sure about this?’ and anybody else will go, ‘Don’t do it!’, Jim goes, ‘More! More! More people singing!’ It works.”

That’s the spirit. And here, for anyone wishing to really immerse themselves in Jim Steinman’s glorious bombast, is a link to the 11-minute remix of This Corrosion.

From marktracks.blogspot.com / youtube.com