One recurrent thought I’ve had during Sri Lanka’s recent slide into economic and political calamity is: “Christ, I hope all the heavy metal guys are okay.” Here’s an updated version of some material I put on this blog in the past about the Sri Lankan heavy metal scene, which helped keep me musically sane during my eight years in the country.

When I arrived in Sri Lanka in 2014, I accepted there’d be certain things I’d gain from the move and certain things I’d lose from it. Among the gains would be the following: sunshine, warmth, delicious spicy food, lots of interesting Buddhist and Hindu temples to explore, access to gorgeous beaches, access to the equally gorgeous Hill Country of the island’s interior, and a chance to see an occasional elephant. Among the losses… Well, I assumed one thing absent from my new life in Sri Lanka would be the opportunity to hear my favourite musical genre played live. No, I definitely didn’t expect to attend any heavy metal gigs there.

Indeed, I imagined the only live music I’d come across would be (1) traditional Sri Lankan music – absolutely nothing wrong with that, of course; and (2) cover versions of the Eagles, Bryan Adams and Lionel Ritchie played by hotel bands to audiences of sweaty middle-aged Western tourists and local would-be hipsters in the country’s holiday resorts – absolutely everything wrong with that.

But one of the pleasantest surprises of my years in Sri Lanka was the discovery that the country has actually a thriving heavy metal scene. Lanka metal is really a thing. Here’s a quick round-up of my favourite headbangers on the island.

Let’s start with probably my favourite Sri Lankan band, Paranoid Earthling. Their Wikipedia entry describes them as a ‘grunge, experimental, psychedelic, stoner rock, heavy metal’ band from Kandy. They started life in 2001 and one of their assets is their spandex-wrapped vocalist Mirshad Buckman, who has the enviable double-advantage of looking a bit like the late, great Ronnie James Dio and sounding a bit like the equally late, great Bon Scott. Well, to me, anyway – admittedly after I’d downed a few pints.

I saw Paranoid Earthling several times and Buckman’s attitude was always entertaining. My first experience of them was in a Colombo pub called the Keg in 2017, when Buckman led the band onstage with a welcoming cry of “How ya motherfuckas doin’ tonight?” Whereas the last time I saw them was at a concert called Colombo Open Air 2019, held just before Christmas on the premises of the quaintly named Otter Aquatic Club (actually a private club with swimming and other sports facilities, just off Bauddhaloka Mawatha in Colombo 7). During Open Air 2019, Buckman was in a memorably grumpy mood and railed between songs against the Sri Lankan media and the low standards of its journalists. I’m glad he didn’t glance behind him. Otherwise, he’d have seen a flashing screen at the back of the stage, advertising the concert’s sponsors, who included the Ceylon Today newspaper.

Among Paranoid Earthling’s best songs are Open up the Gates with its twiddly, thumping guitar sound; the punky, foot-tapping Rock n’ Roll is my Anarchy; and Deaf Blind Dumb, which borrows its stompy bits from Marilyn Manson’s The Beautiful People but is still a blast played live.

Slightly older than Paranoid Earthling are Stigmata, on the go since 1998. I saw them perform a couple of small-scale gigs at the Floor by O bar, next to the grounds of Colombo Cricket Club, and at the 2017 Lanka Comic Con. (In these much-changed times, I wonder if Comic Con will ever happen again.) Stigmata are responsible for an impressive sound that, to me at least, combines the best of Iron Maiden and Sepultura, and their frontman Suresh de Silva is an intelligent, well-read and amusing chap – check out his twitter feed. Other current Stigmata members include the splendidly named Tennyson Napoleon.

That said, I should point out that at Stigmata gigs you may have to wait a while between songs – because the garrulous de Silva does like to talk. And talk, and talk… Well, Sri Lankans generally seem to enjoy a good blether. Totally unlike the Irish, of course.

For a heavier sound – death and black metal – check out the Genocide Shrines, whose ‘lyrical themes’ according the Metal Archives website include ‘tantra / spiritual warfare’, ‘death’ and, er, ‘arrack’. I suppose after you’ve spent all day waging tantra and spiritual warfare, and staring death in the face, you need to relax with a glass of arrack. Aside from their juggernaut sound, their most memorable feature is their fondness for wearing scary masks onstage, Slipknot-style. Though I have to say I was a bit disappointed when I saw them live one time and at their set’s end they ‘rewarded’ their fans by taking their masks off and revealing themselves to be ordinary-looking blokes. That spoiled the mystique somewhat.

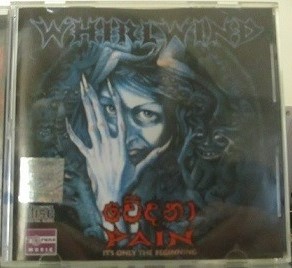

Real old timers of the Lanka metal scene are Whirlwind, established in 1995. I own a copy of their 2003 album Pain, though in my opinion their recorded material doesn’t prepare you for the impressively intense, immersive, even hypnotic sound they conjure up live. I’ve seen them perform twice, at Shalika Hall – more on which in a moment – and at the afore-mentioned Colombo Open Air 2019. Due to scheduling issues at the latter event, they hadn’t had time to do a proper soundcheck beforehand and were forced to give ongoing instructions to the audio engineer between songs. They were understandably peeved, though I didn’t think this affected the quality of their music at all.

The other metal bands I saw during my time in Sri Lanka were Neurocracy, Mass Damnation, Abyss and a couple of young up-and-coming outfits who equally impressed and amused me with their boundless Sri Lankan politeness and gratitude to the audience for turning up to see them. In between their songs they kept saying, “Thank you, thank you very much, thank you for coming, thank you so very much…” And then a minute later they were emitting blood-curdling throaty black / death metal gurgles and screaming “F**k! F**k! F**k!”

Much of what I saw live was at the Shalika Hall on Park Road in Colombo 5, which wasn’t my favourite venue. For one thing, it didn’t really have sidewalls. Both sides of the auditorium opened onto small outside compounds with dilapidated toilets at their ends. This meant the acoustics weren’t great because a lot of the sound seeped out into the night. Conversely, and especially if you turned up at the wrong part of the evening, a great many mosquitoes got in. There were also surreal moments when big bats flapped in from one side, crossed above the heads of the audience and flapped out of the other side – sights that’d be more appropriate for a goth concert than a metal one. Needless to say, the place didn’t have a bar, though you could pop across the road and buy something at the liquor section of the local Food City supermarket.

The Otter Aquatic Club, which hosted the Colombo Open Air 2019 festival, my final experience of Sri Lankan metal, was a much better venue. It provided a pleasant open courtyard with a covered stage for the bands and some other roofed-over spaces (including a makeshift bar) where the audience could shelter if it started to rain. Meanwhile, the Club evidently made efforts to keep its premises mosquito-free because I didn’t see (or feel) one of the bitey wee bastards all night.

I was hoping more heavy metal events would be staged at the club but, of course, fate intervened a couple of months later with the arrival of Covid-19, which put the country’s live music scene into hibernation for two years… And after that came the Rajapaksa-engineered economic and political collapse of 2022, which nearly left the country comatose. Still, I’m seeing flickers of heavy metal life re-emerging now, with upcoming gigs advertised on a few of the above-mentioned bands’ Facebook pages. Fingers crossed.

In the meantime, guys, thanks for leaving me with some fond, Sri Lankan live-music memories… and with an agreeable metallic buzz in my ears.