© Penguin Books

More Halloween-inspired stuff…

The Muse and Other Stories is the second collection of Malaysian horror tales I’ve read recently. The other was My Lovely Skull and Other Skeletons by Tunku Halim, which I reviewed on this blog a few posts ago.

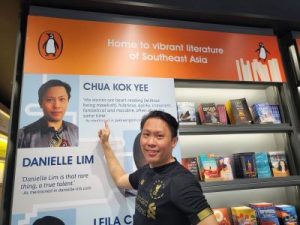

The Muse… is the work of Chua Kok Yee. Like Tunku Halim, he seems to have led a Jekyll-and-Hyde existence – turning into a horror writer after sunset and penning stories of gruesome terror, but during the sunlit hours doing the sort of respectable, wholesome job that your parents would boast about you doing at dinner parties with friends. In Halim’s case, he combined horror writing with being a legal expert who practised corporate and conveyancing law. In Chua’s case (if I’ve located the correct person on social media), the non-horror world knows him as an accountant and ‘Adjunct Professor at University Putra Malaysia’, with ‘a history of working in the food and beverage and consumer goods industry’. Which shows you should never judge by appearances.

There are eight stories in The Muse… It starts strongly with the title tale, a cynical take on the idea that there are beautiful (inevitably female) muses whose only function is to channel inspiration towards great (inevitably male) artists. In reality, this has often been a case of women who were talented artists in their own right having their work ignored and being used, abused and eventually abandoned by those supposedly drawing inspiration from them. See, for example, Camille Claude, muse to Augustin Rodin, an artist herself, who ended up spending 30 years in an asylum; or Dora Maar, muse to Pablo Picasso, a photographer, who ended up needing psychiatric treatment and afterwards took solace in religion.

In Chua’s story, an up-and-coming novelist, and married man, called Mark Lee Wing Sen has an adulterous relationship with a younger woman called Leanne, which seemingly causes a new fervour and intensity in his writing: “…Leanne’s voice kept echoing in my head. The characters, plot and structure of the story flowed into my mind as if it was demanding to be told… I was almost like a new person after Leanne and I started our affair. Throughout the years, she inspired me more than anyone or anything else in the world… Her fingerprints are all over my books. She was my muse; a flowing river of inspiration that provided sustenance to this storytelling.” However, their relationship turns sour and worse, leading to causing obsession, murder and madness. And it doesn’t stop there. The ‘river of inspiration’ continues to flow into Mark from Leanne, but the writing she induces in him now is deadly in nature.

Rather brilliantly, the story’s two heroes – Mark’s agent Arun and a physician called Dr Leong whom he summons when he discovers Mark in shockingly poor health – cite the works of Stephen King when they realise they’re up against a supernatural foe and find themselves speculating on matters of good and evil. In particular, they discuss Father Callahan, the weak-willed priest in Salem’s Lot (1975), who’s unable to stand up to the chief vampire despite being armed with a cross. This is because his faith isn’t strong enough, which renders the cross useless: “At that moment, the cross lost its power and the vampire won.”

© New English Library

Elsewhere, two stories have scenarios where a pair of characters who knew each other as children meet up years later – and with their unexpected reunions come unsettling twists. In Remember, it’s a boy, Ah Hong, who’s suddenly contacted by his long-lost sister, Yee Ching. In Under the Mask, a young girl called Anna encounters a young man called Jiang whom she recalls was an orphan from a charitable institution sent to live in her household for a time. The institution had a programme whereby its orphans were temporarily given ‘a chance to be part of a natural home.’ Remember’s twist is slightly predictable, but the one in Under the Mask is shocking and upsetting.

Several stories showcase Chua’s sense of humour. Sword of Angel amusingly combines a gritty Malaysian crime drama with a fantasy story in the manner of the classic Michael Powell-Emeric Pressburger movie A Matter of Life and Death. Admittedly, this is a pretty warped variation on A Matter of Life and Death. An incompetent gangster gets himself killed whilst on his way to rub out an informer, but then is raised from the dead by a mysterious shapeshifting angel known simply as ‘Mike’. The angel wants him to carry out a different assassination – that of a seemingly innocuous kid called Calvin, who needs to be terminated because “the angel in charge of his Fortune Scale screwed up” and made him supernaturally and harmfully lucky: “He’s not merely ‘lucky’. He is an abomination! You know, luck is not infinite. It comes from a pool, and every time this Calvin drinks from it, someone else is deprived of their rightful share. And I’m telling you, he is guzzling it down. I have to put a stop to it.”

The gangster is less than happy to find himself back in the world of the living in a zombie-like state, bearing the scars of a recent autopsy: “…my body was festooned with stitches. They looked like huge, black centipedes on my arms and thighs. The worst was the huge Y-shaped incision that ran down my torso.” Later, he’s also displeased to learn that he’s not the only dead gangster Mike has reanimated in order to take out Calvin. The story is enjoyable largely because of its hapless and grumbling protagonist and it’s gratifying when he finally figures out a way to turn the tables on the devious Mike.

Similarly, Duke of Zhi has supernatural forces making an intervention in the world of the living and compelling an unfortunate mortal to do their bidding. The reason this time is more mundane. The denizens of hell, led by the narrator’s deceased mother, are concerned about the Loh family, who ‘run the Chinese funeral paraphernalia shop called Loh Paper Enterprise’ and are ‘the best funeral paraphernalia shop in Kuala Lumpur.’ The highlights of their ‘funeral paraphernalia’ are their lavishly detailed paper mansions that, according to Chinese custom, are burnt at funerals in the belief they’ll be passed on to the deceased in the afterlife, where those dead souls can live inside them in comfort.

The narrator gets a glimpse of the paper mansion he purchased from the Lohs for his mother, which now accommodates her in hell: “I was inside a huge hall, filled with exquisite-looking furniture. The chairs were carved from wood, painted in gold and decorated with intricate carvings… A crystal chandelier hung majestically high above, while every inch of the walls was adorned with abstract motifs of animals. Yes, it was the most elegant room I had ever been in…. ‘Hey! I know this place!’ I exclaimed, and jumped to my feet.”

It transpires that the young man set to inherit the Loh family’s business, despite having ‘talent that could rival his grandfather,’ isn’t interested in taking it on. “He doesn’t know his importance to us here in the afterlife, because he’s a non-believer… Despite his gift, he prefers to run a hipster coffee shop instead… Millions of souls would be forced to stay in substandard mansions…” The bewildered narrator is tasked with convincing Loh Junior to abandon the coffee shop, keep the family business going, and keep providing the spirits of the dead with opulent housing. It’s a task that, predictably, he bungles.

Duke of Zhi is amusing with its depiction, in these Trumpian times, of an afterlife whose inhabitants of are just as obsessed with real estate as living souls are. It also touches on a rather sad fact in the real world, which is the art of the “traditional Chinese paper house crafters… is quickly dying as an increasing number of people seek alternative ways to honour their deceased relatives.”

I also like the story because it features the demon Horse-Face, one of the guardians of hell in Chinese mythology. You can see a human-sized effigy of him at Haw Par Villa, the most fascinating museum in Singapore. There, he stands at the entrance of the Villa’s most famous (or infamous) attraction, a graphic representation of the Ten Courts of Hell. I wanted to write something about Haw Par Villa on this blog during the run-up to Halloween 2024, but couldn’t find the time. I will soon, though.

Also touching on local folklore are the stories Akuan, which draws on legends of the harimau akuan, that is, ‘were-tiger, were-leopard or were-panther’, and Feed the Boy, which features a toyol. A toyol, the latter story’s protagonist hears from a mysterious antiques dealer, is “the soul of an unborn baby possessed by a djinn. By nature, a djinn is wild and fiery. It’s the baby’s soul that tempers its more dangerous side, turning it tame and obedient. The soul will be weakened if it’s not fed by the blood of its master. When that happens, the wild nature of the djinn would take over.” But fed by blood, and kept ‘tame and obedient’, a toyal scuttles off to commit crimes on its master’s behalf. It uses its diminutive size to enter other people’s homes, rob them and bring back their valuables.

This suits the protagonist of Feed the Boy, Edry, a hard-up food-delivery man “feeling envious of old school friends who were driving new Japanese cars, while he could only afford a motorcycle. He felt like a loser whenever he delivered food to beautiful houses and condominiums, because their bathrooms alone were more spacious than his rented room.” Edry’s fortunes take an upswing when he acquires a toyol – which disconcertingly has a name, Aamir. He grows rich thanks to Aamir’s ‘nightly heists’ and feeding it with his blood, which it extracts from his toes, seems a small price to pay.

He becomes less keen on the creature when, a few years later, he gets married and his wife becomes pregnant. It’s then that he learns how “sometimes a toyol can become excited by the presence of another child in the household.” What follows, chronicling Edry’s attempts – inevitably doomed attempts, because this is a horror story – to get rid of Aamer, makes this for me the best tale in the book.

With its mixture of the up-to-date and the traditional, and the gruesome and the funny, and with its references to both Malaysian and Western culture, I found The Muse and Other Stories a solidly entertaining read. So, I recommend you to purchase a copy of it and enjoy the products of Chua Kok Yee’s fertile imagination.

Alternatively, of course, you could send your tame toyol crawling into your nearest bookshop, library or Amazon book-warehouse after business hours and procure a copy that way…

From linkedin.com