© Orion Publishing Co

Something has got me thinking about Richard Matheson, the science-fiction and horror author and screenwriter who passed away in 2013 at the age of 87.

What thing? Well, the news that the anti-Covid-19-vaxxers in America, determined to plumb the depths of stupidity to find new reasons for not getting vaccinated, have found the stupidest reason yet. Speculation is rife that the vaccine could turn you in a zombie. You know, like one did in the 2007 sci-fi / horror movie I am Legend, with Will Smith, which was based on Matheson’s 1954 novel of the same name. This has prompted one of the movie’s scriptwriters, Akiva Goldsman, to step up and announce on social media: “Oh. My. God. It’s a movie. I made that up. It’s not real.” In fact, the source of the contagion in the movie wasn’t a vaccine but a virus, genetically reprogrammed by Dr Emma Thompson to combat cancer, going spectacularly rogue.

In Matheson’s novel I am Legend the monsters are vampires, not zombies. Also, what turns people into those vampires isn’t the movie’s lab-reprogrammed virus, but a mysterious pandemic. However, the book’s premise of the world being suddenly and nightmarishly turned upside down and a small number of uninfected humans finding themselves menaced by those who’ve been infected and turned into monsters, including their own loved ones, was one that a young George Romero appropriated for his seminal 1968 movie Night of the Living Dead. In doing so, Romero made it the blueprint for at least 80% of the zombie movies that have lurched across cinema and TV screens ever since.

In the novel, the number of uninfected humans is small indeed: just one, Richard Neville, who is alone in the world during the daytime and then under siege in his fortified house at night, by the vampires that everyone else has turned into. Gradually, Neville, researching the plague, stumbles on scientific explanations for the vampire-like symptoms of its victims, why they drink blood, why they can only be killed by stakes through the heart, and why they have an aversion to sunlight, garlic and crucifixes. I am Legend also ends with an unnerving psychological twist. Neville, who’s spent his days roaming the surrounding city and staking the slumbering vampires, realises that the vampires are now the normal ones and he’s become the monster of everyone’s nightmares, the deadly legend of the title.

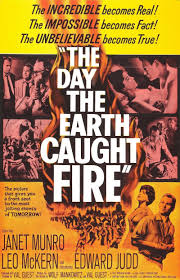

It’s a pity that though I am Legend was filmed on several occasions, and though Matheson lived to a venerable age, he never got to see a satisfactory celluloid version of it. The novel received its first film treatment in Italy, where Rome unconvincingly stood in for Los Angeles, with the cheaply and incompetently made L’Ultimo Uomo della Terra (The Last Man on Earth). Neville was played by Vincent Price, whom Matheson admired as an actor but thought was miscast in the role. L’Ultimo Uomo della Terra was at least fairly faithful to the book, unlike the subsequent film versions, 1970’s The Omega Man, with Charlton Heston, and the 2007 one. In The Omega Man the vampires have become a group of demented albino mutants called, with an unsubtle reference to Charles Manson, the Family. In the Will Smith version of I am Legend they’re even less impressive, a bunch of bald, hyperactive zombies animated by some shoddy CGI.

Both the later movie versions lack the courage to portray Neville as being totally alone and eventually have him encounter other, as yet uninfected survivors. They also lack the courage to include Matheson’s game-changing ending. Instead, they close with Heston and Smith depicted as Christ-like figures who nobly sacrifice themselves for the good of what’s left of humanity. Neville was a more interesting character when he discovered he’d become a bogeyman. Still, disappointing though all three film versions are, there’s at least a good graphic-novel adaptation of I am Legend available.

© Gold Medal Books

The more I reminisce about Matheson, the more I realise what a wonderful and influential writer he was. His other big – though ‘big’ perhaps isn’t the most appropriate adjective – novel of the 1950s was The Shrinking Man (1956). Its hero, an archetypal middle-class American male called Scott Carey, is exposed to a radioactive cloud that causes his body to shrink at the rate of a seventh of an inch every day. Thereafter, Carey’s world turns nightmarishly upside down too, though at a more gradual rate than Richard Neville’s. First, he experiences psychological and sexual humiliation as he finds himself increasingly dwarfed by his normal-sized wife. Following an assault by the family cat, no longer a loveable moggie but a carnivorous monster, the now-tiny Carey loses all contact with humanity and finds himself trapped in his house’s basement where the dangers facing him become formidable indeed. A common spider, for instance, takes on elephantine proportions. And Carey’s shrinking doesn’t stop, let alone get reversed. At the book’s close, he muses, “If nature existed on endless planes, so also might intelligence.” Thereafter, he dwindles away into infinity.

A year after its publication, the novel was filmed as The Incredible Shrinking Man, directed by Jack Arnold and with Matheson providing the script. Matheson was unhappy with how Arnold structured the film. He told the story in linear fashion, whereas Matheson wanted it to begin with the shrunken Carey in the basement, reliving what had happened to him via a series of flashbacks. However, it’s still one of the best science fiction movies of the 1950s. It crucially retains the novel’s bleakly philosophical ending. I can remember seeing the film on TV as a kid and being genuinely upset when the ending defied my expectations that things would finish on an upbeat note. The Incredible Shrinking Man was, incidentally, one of the great J.G. Ballard’s top ten favourite sci-fi movies.

© Sphere Books

As well as novels, Matheson was a prolific writer of short stories, many of which were collected in four books called the Shock series. Shock 1-4 were published in Britain in the 1970s by Sphere Books, who decorated the covers with lurid and gory images – the antithesis of the unsensational, non-violent and thoughtful works inside. The stories I remember best include Long Distance Call, about a woman plagued by mysterious phone calls that, she discovers, emanate from a local cemetery into which the telephone wire has blown down; The Children of Noah, about a motorist who finds himself in Kafkaesque predicament when he breaks the 15-miles-per-hour speed limit of a tiny American town called Zachary; and the brilliant The Splendid Source, in which a man embarks on a quest to find out where dirty jokes really come from.

Long Distance Call was one of several Matheson stories that were turned into episodes of the celebrated TV anthology series The Twilight Zone (1959-64). The best of these, adapted by Matheson himself, was of course Nightmare at 20,000 Feet. In this, William Shatner essayed his second-most-famous role, that of a just-released psychiatric patient who’s on board a plane and, looking out of the window, sees a gremlin dismantling one of the engines on the wing. Whenever he tries to alert the crew and fellow passengers, the beastie inconveniently disappears from view. Particularly memorable is the moment when the traumatised Shatner dares to peek through the window again and discovers the gremlin pressing its face, which resembles that of a hare-lipped teddy bear, against the outside of the glass and staring in at him. The episode was remade as a segment of the movie version of The Twilight Zone in 1983, with John Lithgow in the Shatner role, and ten years later it received the ultimate accolade – it was spoofed in a Treehouse of Horror edition of The Simpsons, with Bart Simpson the only passenger on the school bus able to see a gremlin sabotaging its engine. This version was called Nightmare at 5½ Feet.

© Universal Pictures

Other episodes that Matheson penned for The Twilight Zone were also influential. A World of Difference is about a businessman who makes the mind-blowing discovery that he’s a fictional character and his life is actually a movie. Furthermore, the movie has just had its production halted, meaning he’ll have to live in the ‘real’ world as the declining, drunken movie star who’s been playing him. This clearly informs Peter Weir’s 1998 film The Truman Show. Meanwhile, Little Girl Lost tells the tale of a child who, one night, falls from her bed and into another dimension, a mysterious, misty void from which she can hear her parents’ concerned voices but can’t escape. A young Steven Spielberg no doubt saw and remembered this one, because the same idea features in 1982’s Spielberg-produced Poltergeist, though this time the little girl is sucked into the other dimension through the household TV set. And yes, The Simpsons spoofed it too in Treehouse of Horror.

Steven Spielberg has much to thank Matheson for. Matheson’s short story Duel, based on an experience he had on November 22nd, 1963 – of driving home depressed at the news of Kennedy’s assassination and being harassed by a large, tailgating truck – was filmed as a TV movie in 1971 by Spielberg and gave the young director his first big critical success. Again, Matheson wrote the script. Duel-the-movie has motorist Dennis Weaver and the psychopathic driver of a 1955 Peterbilt 281 truck get into a deadly game of cat and mouse around the roads and highways of rural California. We never see the truck driver himself, just his immense, bellowing, dinosaur-like vehicle. Duel is the archetypal man-versus-machine story and, again, has been influential. Stephen King basically rewrote it (but upped the ante by adding lots of malevolent vehicles) with his short story Trucks, which he later filmed as Maximum Overdrive (1986).

The made-for-television movies that filled American TV schedules in the 1970s kept Matheson busy. As well as Duel he scripted The Night Stalker (1972) about a reporter called Carl Kolchak (Darren McGavin) who investigates a series of killings in modern-day Los Angeles and discovers that the perpetrator is a vampire. The Night Stalker was successful enough to eventually spawn a TV show called Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974-75), also starring McGavin, in which Kolchak investigated other strange cases involving monsters and supernatural phenomena. Though short-lived, the show was a major inspiration for Chris Carter, whose massively popular The X-Files (1993-2018) had a similar theme. Carter acknowledged his debt to Kolchak by having Darren McGavin guest-star in two X-Files episodes.

Meanwhile, the TV anthology movie Trilogy of Terror, from 1975, was based on three of Matheson’s short stories. The first two segments are unmemorable, but the third one, which Matheson scripted from his story Prey, is great. It stars Karen Black as an insecure woman who tries to shore up her relationship with her boyfriend, a lecturer in social anthropology, by buying him an antique ‘Zuma fetish doll’ as a birthday present. The doll is a hideous-looking thing and sports a many-fanged grin resembling a Venus flytrap. Before she can give the doll to its intended recipient, it comes to violent, gibbering life and she spends the evening fighting it off in the confines of her apartment. Black’s plight is the inverse of the shrinking man’s. She’s normal-sized and the threat she faces is tiny, but terrifying. This also creates the template for Joe Dante’s movie Gremlins in 1984. In particular, the scene in Gremlins where Frances Lee McCain fights off a horde of the sneering, reptilian mini-monsters in her kitchen, employing a blender and a microwave oven as weapons, is very reminiscent of Trilogy of Terror.

When he wasn’t writing novels, short stories and television scripts, the ever-industrious Matheson was writing for the cinema. In the early 1960s, he scripted several of the movies based on works by Edgar Allen Poe that were made by American International Pictures and directed by Roger Corman: The House of Usher (1960), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963). All told, Matheson did a good job of preserving the original stories’ gloomy, clammy spirit, whilst meeting the commercial demands of a studio and a director who were already famous for their exploitation movies, and keeping engaged a star – Vincent Price – whose performances tended to slip into the knowingly hammy when his material bored him. The movies aren’t the most faithful adaptations of Poe, but they’re surely the most fondly remembered ones.

© Academy Pictures Productions / 20th Century Fox

Matheson also worked on British movies. For AIP’s trans-Atlantic rival, Hammer Films, he scripted The Devil Rides Out in 1968 and managed to turn Dennis Wheatley’s bloated, reactionary novel about upstanding Anglo-Saxon aristocrats fighting a bunch of ghastly Satan-worshipping foreigners into something rather good. And in 1973, he adapted his haunted-house novel Hell House for the screen. The result was The Legend of Hell House, directed by John Hough and starring Roddy McDowall, Clive Revill, Pamela Franklin and Gayle Hunicutt as psychic investigators trying to get to the bottom of terrifying supernatural manifestations in the titular mansion. The movie’s ending, which has the surviving investigators finding a hidden sanctum where the psychic forces are emanating from an embalmed body, played by a very un-embalmed-looking Michael Gough, is pretty stupid, which Matheson himself admitted. Still, John Hough directs the film’s scary set-pieces with vigour and there’s an unsettling electronic score by Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson.

Matheson was a modest soul and in interviews he usually seemed puzzled that so many people could be so inspired by his work. He might have ended up a very rich man if, like his famously litigious contemporary Harlan Ellison, he’d bothered to sue every filmmaker and writer who’d ripped off his ideas. Mind you, he’d probably have spent all his time in court, so I’m glad he just turned the other cheek and devoted that time instead to writing his marvellous stories.

© Cayuga Productions / CBS Productions