© Penguin Books

Continuing my look at On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, both the best James Bond novel (published in 1963) and best Bond film (released in 1969). We rejoin the book and film at the moment in their plots when Bond attempts to infiltrate the headquarters of his arch-enemy Ernst Stavro Blofeld, high in the Swiss Alps…

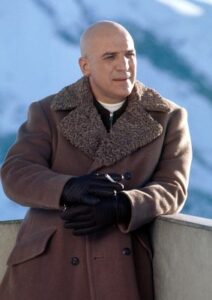

Bond duly goes to the Piz Gloria, pretending to be Sir Hilary Bray – and here the film glaringly contradicts the continuity established by its predecessor. At the climax of You Only Live Twice-the-movie Bond and Blofeld have a face-to-face confrontation, but in OHMSS Blofeld doesn’t recognise Bond at all. Actually, Bond might be forgiven for not recognising Blofeld either, for the filmmakers decided to recast the role of Blofeld too. Not only do we have Sean Connery replaced by George Lazenby in OHMSS, but we have the goblin-like Donald Pleasence replaced by the bigger and more physical Telly Savalas. To be honest, Savalas is a shade too thuggish-looking for the role, but he’s believable when doing the strenuous things required by the script, such as leading a group on skis in pursuit of Bond and wrestling with him during a breakneck bobsleigh ride. Much as I like Donald Pleasence, I couldn’t imagine the sinister English character actor bouncing about on a bobsleigh.

What’s officially going on in Blofeld’s clinic, Bond learns, is that a group of young female patients are receiving treatment for food allergies. What’s unofficially happening is that Blofeld is brainwashing them whilst simultaneously developing various destructive bacteriological agents in his laboratories. The brainwashed ladies are to become his ‘angels of death’ and, when they return home, they’ll release those agents to decimate whole species of livestock and crops. Blofeld finds out who Bond really is but the secret agent manages to grab a pair of skis and stages an epic night-time escape from Piz Gloria. Blofeld’s henchmen pursue, but Tracy turns up in time to rescue him. Afterwards, he links up with Draco again and persuades him to launch an audacious attack on Piz Gloria using helicopters and his Unione Corse men. Blofeld’s plans go up in smoke, although Blofeld himself escapes – despite Bond’s best efforts – using a bobsleigh. Mission accomplished, Bond proceeds to marry Tracy, and things hurry to their tragic conclusion with Blofeld making an unexpected appearance during their honeymoon.

Both the book and film proceed along similar lines here, although it’s interesting to see how certain aspects of the 1969 film are expanded from what Fleming put in his 1963 book. In 1963, Blofeld was content to wage bacteriological warfare against Britain and Ireland, devastating their wheat, chickens, beef, potatoes, etc. By 1969, Blofeld has widened his horizons – it’s the whole world’s food supply he wants to decimate. Accordingly, the ‘angels of death’ undergo an upgrade too. In the novel they’re a prim, middle-class, goody-two-shoes bunch, all from the British Isles. Rather disdainfully, Bond reflects: “The girls all seemed to share a certain basic girl guidish simplicity of manners and language, the sort of girls who, in an English pub, you would find sitting demurely with a boyfriend sipping a Babysham, puffing rather clumsily at a cigarette and occasionally saying, ‘Pardon’. Good girls who, if you made a pass at them, would say, ‘Please don’t spoil it all’, ‘Men only want one thing’, or, huffily, ‘Please take your hand away’.” One of them even takes umbrage when Bond jokingly compares them to the girls in the St Trinian’s films: “Those awful girls! How could you ever say such a thing!”

From wikipedia.org / © ETH-Bibliothek

In the film, the angels come from all over the world and they’re way more glamorous. Indeed, a good number of the actresses went on to brighten up my adolescence during the 1970s with appearances in various cult films and TV shows. There’s Angela Scoular, who also starred in an ‘unofficial’ Bond movie, the dreadful, zany, swinging-1960s comedy Casino Royale (1967); Catherine Schell, who’d be a regular in Gerry Anderson’s sci-fi series Space: 1999 (1975-77); Norwegian actress Julie Ege, who appeared in the kung-fu horror movie Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires (1974), a co-production between legendary Hong Kong studio Shaw Brothers and legendary British studio Hammer Films; Jenny Hanley and Anouska Hempel, both of whom appeared in Hammer’s ultra-tacky Scars of Dracula (1970); and the impeccable Joanna Lumley. In the late 1970s, of course, Lumley would play Purdey in the revival of The Avengers (1961-69), The New Avengers (1976-77). In fact, you could argue that OHMSS-the-move features three Avengers actresses. In addition to Diana Rigg and Joanna Lumley, the face of Honor Blackman – who played Cathy Gale in The Avengers and Pussy Galore in 1964’s Goldfinger – is shown fleetingly during the credits sequence.

Nobly, mindful of Bond’s relationship with Tracy, Fleming has his hero seduce just one of the girls – something he does purely in the line of duty. The filmmakers are less inhibited and for a little while on Piz Gloria Lazenby behaves like a fox in a chicken coup, shagging left, right and centre. The movie also plays up the humour of the situation. Sir Hilary Bray is supposed to be Scottish, so Bond dons full Highland dress before going to dinner with his hosts and their supposed patients. Yes, after having a Scotsman play Bond for five films, producers Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman wait until he’s played by an Australian before they pop him into a kilt. This enables the Angela Scoular character to use her lipstick to write her room number on the inside of Bond’s thigh, under the table, which prompts the following exchange: “Anything the matter, Sir Hilary?” “A momentary stiffness… caused by the altitude, no doubt.” If the dialogue for this Bond movie sounds sharper than usual, it’s probably because Simon Raven, the famously dissolute English author, was hired to polish it.

When Bond escapes from Piz Gloria, Peter Hunt and his crew predictably pump up the action scenes beyond what was in the book, but I’m not complaining. Even 56 years later, the scenes where Lazenby skis, runs, drives and fights for his life are very impressive and Hunt makes good use of his experience as a film editor – the action has a frenetic quality that, viewed now after the Bourne movies (2002-16), seems far ahead of its time. Similarly ramped up is the climactic assault on Piz Gloria mounted by Bond, Draco and his gang. In the book it comes across as a brief ‘smash-and-grab’ raid but in the film it’s a full-on battle, complete with grenades, flame-throwers and flying bottles of acid. Rarely does the pulse quicken as much as it does here when Monty Berman’s James Bond Theme kicks in in the midst of the mayhem.

One change the filmmakers made to the plot that I think improves on the book is Tracy being captured by Blofeld. In Fleming’s original, after Tracy come to Bond’s aid, she disappears into the background again. In the movie, Blofeld triggers an avalanche that leaves Tracy unconscious and at his mercy, and Bond missing, presumed dead. When Bond, who of course isn’t dead at all, goes to Draco for help, the Corsican mafia boss has a very real reason for giving him help – his daughter’s life is at stake. It also allows Peter Hunt to show Savalas flirting, with an obviously menacing undercurrent, with Rigg at his mountaintop HQ. Again, I don’t think poor old Donald Pleasance would have done the flirting bit very convincingly.

Fleming depicts Bond and Tracy’s wedding as brief and low-key, but again the film makes it a big, opulent affair. M, Q and Miss Moneypenny (who’s tearful, for obvious reasons) are in attendance, as are Draco’s henchmen, many of whom spent the early part of the film getting the shit beaten of them by Bond. However, both the book and the film converge for the ending, which is as melancholy and understated as it is shocking. There hasn’t ever been an ending to a Bond film like this one – well, not until 2021’s No Time to Die.

© Eon Productions / United Artists

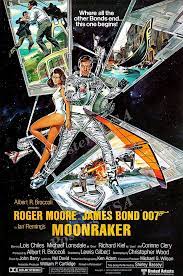

Indeed, it’s annoying that the filmmakers saw fit to follow this with 1971’s Diamonds are Forever, which gets Bond’s revenge on Blofeld out of the way in the first ten minutes, and then becomes a big, lazy, jokey and ludicrous Bond epic that would be the blueprint for Bond films later in the 1970s after Roger Moore had inherited the role. For a proper, spiritual sequel to OHMSS, I think you have to look to the gritty Timothy Dalton Bond movie Licensed to Kill in 1989.

OHMSS-the-film received some unfavourable reviews and made less money than its predecessors, and for years it was regarded as the runt of the litter of the 1960s Bond-films. Much of the animosity towards the film was because George Lazenby played Bond in it for the first and only time. (By Diamonds are Forever, Broccoli had managed to patch things up with the truculent Connery and got him back into the role.) Lazenby certainly isn’t a great actor, but I would argue that because this is a different sort of Bond movie, one where its hero appears vulnerable and wounded, the awkward and uncertain Lazenby actually fits the film. He’s believable in terms of what the character has to endure. I couldn’t imagine ‘Big Sean’ breenging through the movie in his usual manner and having the same emotional impact.

Happily, though, OHMSS has been re-evaluated and today is regarded as one of the best of the series. In fact, when 007 Magazine ran a poll in 2012, it was voted the greatest James Bond film ever. Cubby Broccoli’s daughter Barbara and her half-brother Michael G. Wilson, who were running the Bond franchise in 2021, were so aware of OHMSS’s improved reputation that they tried grafting bits of it onto No Time to Die. Both films share, for example, a figure grasping a trident in their credits sequences, Louis Armstrong singing We Have All the Time in the World on their soundtracks and, obviously, downbeat endings. Though I feel No Time to Die’s nods to OHMSS only highlight the fact that it’s the lesser of the two movies.

A happier tribute to OHMSS occurs in Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010). When Leonardo DiCaprio, Elliot Page, Tom Hardy and co. hit the ‘third level’ and find themselves on a snowy mountaintop battling opponents on skis, it’s obvious what film is being referenced. Indeed, Nolan has more-or-less said that OHMSS is his favourite Bond movie. (He’s also named Dalton as his favourite Bond actor, so he’s clearly a 007 fan after my own heart.)

And much of the film’s greatness is due to the fact that, no matter what innovations were brought to the table by the talented Peter Hunt and his crew, it owes a lot to the original Ian Fleming novel – which, for me at least, is the best of the Bond books too.

From wikipedia.org / © ETH-Bibliothek