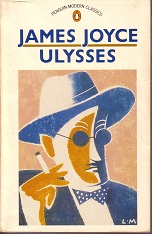

© Penguin

Today is June 16th, a day that connoisseurs of Irish literature will recognise as Bloomsday, the date on which the events described in James Joyce’s epic novel Ulysses took place in Dublin in 1904. Literary legend has it that on the real June 16th, 1904, Joyce and his muse and future wife Nora Barnacle – “She stuck to him like a limpet!” one of my university lecturers liked to quip – acquired carnal knowledge of each other for the first time. And since 2022 is the centenary of Ulysses‘ original publication in 1922, today is a special Bloomsday indeed.

Ah, Ulysses. I first encountered it in 1982, when I spied a hefty copy of it reposing on a rack in Whitie’s, the main bookshop in my hometown of Peebles. As someone who was into books and writing, I decided that this was something I ought to experience. So I purchased it, lugged it home and started reading: “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from a stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed…”

The task took me several months. This amused my school English teacher Iain Jenkins, who cheerfully admitted that he’d never read Ulysses and never intended to, believing it to be a pile of pretentious twaddle. Whenever he bumped into me, he’d mischievously inquire how I was getting on with Joyce’s masterwork, assuming sooner or later I’d throw in the towel and never get to the end of Bloomsday.

But I persevered. The months passed. April, May, June, July… In fact, the countries I was in changed too, for I finished school in May and left Scotland for some pre-university wandering: France, Northern Ireland, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, Belgium… And I took Ulysses with me.

As far as I can remember, it was in a chilly youth hostel in Brussels in November, as far away from Dublin on June 16th as seemed possible, that I navigated the book’s final section. This is the lengthy stream of consciousness going on inside Molly Bloom’s head that ends: “…yes I said yes I will Yes.”

I should point out that during those half-dozen months I didn’t just read Ulysses. Over the same period I remember reading stuff by Ernest Hemmingway, Ray Bradbury, Jerome K. Jerome, Sean O’Faolain and Anthony Burgess. Incidentally, Burgess, who was still alive at the time, was probably the world’s most famous Joyce authority and had written a book about him called Here Comes Everybody in 1965. It actually helped that I would read a section of Ulysess, leave the book for a couple of weeks, read something by someone else, and return to it. I’d discovered how episodic it was, each episode having its own theme, style and literary gimmicks, and reading it this way gave me time to process one episode before I started on the next.

Famously, the episodes of Ulysses parallel the adventures of the mythological Ulysses in Homer’s Odyssey, although this didn’t dawn on my 16 / 17-year-old self until the scene set in Barney Kiernan’s Pub. This climaxes with the Citizen hurling a biscuit tin at Leopold Bloom’s head, which I realised was a representation of Polyphemus the Cyclops lobbing a rock after the escaping Ulysses in the Odyssey.

How did I find it? Well, there were times early on when it was bloody hard work. At one point in June, while I was in France, I nearly did give up. I was possibly mired in the book’s third section, which is notoriously abstruse. But later it all seemed to click for me. Joyce’s prose, however complicated it got, settled into a comforting, familiar rhythm. The external and internal voices of its two main characters, Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, became like the banter of old friends. And when I finished, I felt I’d read a truly great book. I suspect, though, my admiration for it then was like the admiration a climber feels for the grandeur of Mount Everest while standing on its summit. The admiration is mingled with his or her own sense of achievement at having climbed the beast.

One thing that impressed me was that Joyce had obviously gone out and done some living. He knew and was able to convincingly portray Dublin and its inhabitants – all its inhabitants, not just the posh or arty ones. Perhaps that’s why I was never enthused by the works of Virginia Woolf, which I tackled soon afterwards. Surely Woolf and her affected Bloomsbury (as opposed to Bloomsday) set wouldn’t have lasted long in Barney Kiernan’s Pub.

Talking of pubs, while I was wandering around Switzerland in October that year, I happened across an establishment in Zurich called the James Joyce Pub. It cashed in on the fact that much of Joyce’s post-Ireland life had been spent in Zurich. Eagerly, I popped inside for a Guinness. What a disappointment the place was. It was full of people who regarded themselves as intellectuals and took themselves way too seriously – the opposite of what I believed Ulysses, in which all human life seemed present, was about.

And now? Well, I wouldn’t like to read the book again. One thing I’ve noticed about growing older is that, as the years and experiences accumulate, it becomes harder to feel impressed. New people I meet, whom I would have found fascinating in my youth, make less of an impression because I’ve met their type before and their personality traits no longer seem special. The same goes with books. Literary razzle-dazzle that might have blown me away when I was younger just annoys me in my middle-age. Sorry, I’ve seen all that already. When I read Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) in my twenties, I thought, “Wow! This the profoundest book ever!” Whereas I read Kundera’s Slowness (1995) last month and thought, “Oh, stop showing off, you poser.” I’d hate it if I read Joyce’s opus again and reacted with the same weariness.

Some things are best left in the past. And though I still think it’s a great book, Ulysses is probably one of them.

From wikipedia.org