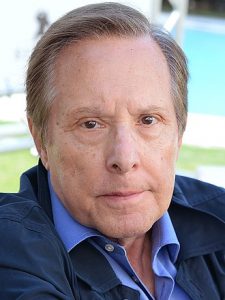

From wikipedia.org / © Guillem Medina

I was very young when a film made by William Friedkin, the great American director who died earlier this month, first unsettled me. I was about eight or nine years old when I learnt that the BBC was going to show his 1968 movie The Night They Raided Minsky’s one evening. The TV listings in the newspaper assured me this was a comedy film, starring the zany performer Norman Wisdom, who could best be described as Britain’s answer to the USA’s Jerry Lewis. When I was eight or nine, I absolutely loved Norman Wisdom. I adored the knockabout slapstick he specialised in and the gormless man-child persona he affected for his roles. You couldn’t dissuade me from my belief that such efforts as The Bulldog Breed (1960), in which Norman joins the Royal Navy and ends up being launched into outer space in an experimental rocket, or The Early Bird (1965), in which Norman plays a humble milkman who takes on and outwits a ruthless dairy corporation that’s trying to muscle in on his milk-delivery patch, were the best movies ever.

Thus, I was rather perturbed when I sat down to watch The Night They Raided Minsky’s and discovered it wasn’t a typical Norman Wisdom vehicle. Rather than a knockabout comedy, it was a nostalgic, bitter-sweet film about knockabout comedy, as it was enacted in American burlesque theatres in the 1920s. It was also, I realised to my horror, a bit risqué. It told the story of a naïve Amish girl (Britt Ekland) who runs away to the big city, tries to fulfil her dream of making a career onstage, and ultimately but accidentally invents the striptease routine. Every time the film featured a boob gag, I’d nervously look over my shoulder in case my parents had entered the room.

Needless to say, since then, my opinion of Norman Wisdom’s oeuvre has been revised, downwards. I’ve also managed to see The Night They Raided Minsky’s again, at an age when I no longer found it baffling and was able to appreciate its tone and subject matter. It’s not great, but it’s likeable and benefits from a marvellous cast: Ekland, Elliott Gould, Jason Robards, Forest Tucker, Harry Andrews, Denholm Elliott, Joseph Wiseman and Bert Lahr, who’d played the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz (1939). In the film’s final images, Lahr is shown ruefully treading the boards of the now-deserted theatre, after the titular police raid, with the implication that as far as burlesque is concerned, this is the end of an era. (It was also the end, alas, for Lahr, who died of cancer during production.) And, credit where it’s due, Wisdom is pretty good in the movie too.

© Tandem Productions / United Artists

The Night They Raided Minsky’s was film number three on William Friedkin’s CV and was a credible third film for a director in his early thirties. Mind you, based on it, you’d hardly predict the stunning commercial and critical success that awaited him in the next decade.

Half-a-dozen years later, I was also unsettled by the second Friedkin movie I saw, 1977’s Sorcerer, shown on TV while I was a typical teenager, i.e., I saw myself as hardened, cynical and incapable of being fazed by anything. Sorcerer made an impression because it did faze me.

A remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953), it tells the story of four dregs of humanity – a Mexican hitman (Francisco Rabal), a Palestinian terrorist (Hamidou Benmessaoud), a French businessman fleeing fraud charges (Bruno Cremer) and an Irish-American crook who has the Mafia after him (Roy Scheider) – hired to drive two ramshackle trucks carrying two loads of volatile explosives across a natural assault course of overgrown jungle paths, rocky mountain-trails and decrepit rope bridges. The explosives, ancient sticks of dynamite so decayed they’ve started to leak their prime ingredient, nitroglycerin, are needed to extinguish a fire that’s consuming an oil well in a remote part of South America.

I was rattled by Sorcerer because I wasn’t prepared for how brutal, cynical and hard-as-nails it was. From its unflinching images of accident victims – bloodied ones after the getaway car Schneider and his gang are using crashes in New Jersey, charred ones after the initial explosion at the oil well – to the squalor of the village from which the four men set out on their ultra-dangerous mission – mud, shacks, chickens, feral dogs, feral policemen, Big-Brother-type political posters bearing the features of the local military dictator, barefoot kids whose only function is to mindlessly chase after the jeeps that occasionally rumble through the place, sordid bars where the only thing missing is the author Malcolm Lowry sitting on a barstool, getting sozzled on tequila – to everything that nature flings against them during their nightmarish odyssey – torrential rain, sweltering heat, choking vegetation, raging torrents, treacherous quicksand and toppled trees – Sorcerer knocked me for six. And ladled over that is the film’s relentless nihilism, which makes it plain there’s going to be no happy endings for anyone. Teenaged kid, Sorcerer seemed to tell me, you still have some growing up to do!

© Universal Pictures / Paramount Pictures

The film’s master set-piece, of course, is the sequence where the quartet have to get their trucks across a falling-apart rope bridge, above a swollen river, during a mini-hurricane – which at one point sends a fallen tree scudding along the water and crashing into them. Appropriately, this provides the vertiginous image that appears on Sorcerer’s poster. The film’s stunt coordinator was the Bud Ekins, who’d doubled for Steve McQueen during the climactic motorbike chase in The Great Escape (1963), though I’ve read that the cast did many of the stunts themselves. There’s also a pulsing, needling soundtrack by German prog-rock band Tangerine Dream, which Friedkin wisely refrains from overusing.

On its release, Sorcerer was a financial disaster – coming out at the same time as a wee film called Star Wars (1977) probably didn’t help – and received a critical drubbing. Leading the charge was Britain’s notoriously prissy, reactionary whinging-film-critic-in-chief Leslie Halliwell, who lamented, “Why anyone should have wanted to spend twenty million dollars on a remake of The Wages of Fear, do it badly and give it a misleading title is anybody’s guess. The result is dire.” Happily, Sorcerer had now been re-evaluated and is recognised as one of the very best American action-thrillers of the 1970s.

Roy Scheider turned up again in the next William Friedkin movie I encountered, 1971’s The French Connection, the one that put him on the map and won him a Best Director Oscar. Lauded for its grittiness, as exemplified by Gene Hackman (who bagged an Oscar too) in the lead role of rumpled and rowdy detective Eddie ‘Popeye’ Doyle, The French Connection manages to have its cake and eat it – for while it oozes with authentic, documentary-style 1970s New York grime and sleaze, it also serves up some classic, if hardly realistic, action set-pieces. Most notable of these is the legendary chase between a car and an elevated train, which Friedkin filmed without proper permission. The sequence also necessitated the head of the New York Transit Authority being bribed so that one of their trains could be ‘borrowed’. Indeed, it sounds like Friedkin indulged in the same sort of ‘guerilla filmmaking’ that nine years later Lucio Fulci did when he shot the New York parts of his horror opus Zombie Flesh Eaters (1980) – he’d have his crew turn up in city locations, start filming and then run like hell when the police appeared. (There. I’ve just mentioned William Friedkin in the same sentence as Lucio Fulci. The famously cantankerous Friedkin would hate me for that.)

Incidentally, classic though The French Connection is, I think its sequel, John Frankenheimer’s imaginatively titled French Connection II (1975), is equally good. This sees Doyle pursue Alain Charnier, the smooth French drug-mastermind of the original film (who was played by Fernando Rey, actually a Spaniard), back to Marseille. This leads to culture clashes galore. Predictably and hilariously, Doyle shows zero diplomacy while dealing with the locals, including the exasperated Marseille police force. He’s surely the most boorish American to ever descend upon France – well, until 2018, when Donald Trump rocked up there for the 100th anniversary of the Armistice at the end of World War One.

© Philip D’Antoni Productions / 20th Century Fox

Stay tuned for the second instalment of this entry, when I talk about my experiences of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), Cruising (1980) and Killer Joe (2011)!