© Universal Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

As yet another grim reminder that time stops for no man or woman, and that I’m gradually de-evolving into a doddery, senile old git, I’ve just read in a newspaper that it is now, exactly, thirty years since the release of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993), the epic monster movie about dinosaurs being cloned from ancient bits of DNA to be put on display in a lavish theme park. It was based on a novel, published three years earlier, by Michael Crichton, and of course it led to a franchise of sequels and reboots that, despite being increasingly lame, generated billions of box-office dollars.

Wow! Thirty years? Was the original Jurassic Park movie really that long ago?

Anyway, readers, brace yourselves for a big shock. I thought the 1993 movie was pretty lame itself. Although a lot of people nowadays view the original Jurassic Park as a classic – here’s a hot-off-the-presses feature at the BBC website’s ‘Culture’ section praising it for how it ‘made scary movies accessible for young children’; and here’s another feature at the Guardian praising it for its prescient warnings about ‘self-styled geniuses’ who exploit new technology for their aggrandisement without thinking through the potential consequences – I found it a big let-down.

This was because I made the mistake of reading Crichton’s Jurassic Park-the-book before I went to see Spielberg’s Jurassic–Park-the-movie, and I felt miffed when what’d I’d visualised in my head during the book failed to materialise on the cinema screen. And before you read further, here’s a spoiler alert. This entry will give away a lot about the plots of both the book and the film.

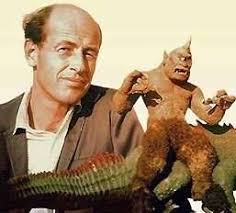

Three decades ago, I certainly had high hopes for the film. Firstly, with Spielberg at the helm and a ton of Hollywood money behind it, Jurassic Park looked like being a very rare beast, a dinosaur movie with proper dinosaurs in it. I’ve always loved the idea of dinosaur movies, but apart from those ones where the prehistoric beasties were powered by stop-motion animation – like the silent-movie version of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1925) and the original King Kong (1933), whose dinosaurs were animated by Willis O’Brien, and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), One Million Years BC (1966) and The Valley of Gwangi (1969), whose special effects were the work of the late, great Ray Harryhausen – dinosaur movies before 1993 had contained dinosaurs that looked, frankly, rubbish.

© Universal Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

I’m thinking of ones where the dinosaurs were plainly stuntmen lumbering about in rubbery dinosaur suits, like The Land Unknown (1957). Or magnified glove puppets, like The Land that Time Forgot (1974). Or unfortunate modern-day lizards who’d also been magnified and had had fake spikes, horns and fins glued onto them to make them look big and fierce. The worst offender in that last category is surely Irwin Allen’s terrible 1960 remake of The Lost World, during which Claude Rains exclaimed at the sight of one supposed sauropod: “It’s a mighty brontosaurus!” While I was watching the film on TV, at the age of ten, I yelled back: “No, it’s not! It’s just a stupid iguana!”

The big-budget Jurassic Park was going to employ all the latest advances in animatronics and computer-generated imagery to get its dinosaurs right, so I wouldn’t have to worry about having my intelligence insulted by the spectacle of men in monster suits and overblown puppets and lizards.

Secondly, there was a buzz about Jurassic Park because it was rumoured that, for the first time in yonks, Spielberg was going to do something dark. He’d spent the past dozen years making movies with unbearably-high schmaltz levels: movies about cute aliens phoning home (1982’s ET), and ghostly pilots moping about their still-alive girlfriends (1989’s Always), and Robin Williams turning out to be Peter Pan (1991’s Hook). Once upon a time, though, he’d directed punchy, at times nightmarish films like Duel (1972) and Jaws (1975). Prior to Jurassic Park’s release, I was told by more than one film magazine to expect Spielberg to be back to his old schmaltz-free best. Supposedly, Jurassic Park was going to be like Jaws on dry land.

As for Michael Crichton’s original novel – well, it would never be mistaken for great literature but, reading it, I did think that with cutting-edge special effects and a skilful director it could make a hell of a movie. Many of its scenes seemed intensely cinematic. Actually, this wasn’t a surprise because Crichton himself had made films. Most notably, he’d wrote and directed 1973’s Westworld, which is about a futuristic theme park that allows its visitors to enact their most homicidal fantasies in mock-ups of the American Wild West, medieval Europe and Roman-era Pompeii. These are populated by scores of human-like robots whom it’s okay to shoot or hack or stab to death because they can’t actually die. Of course, a glitch in the system eventually compels the robots to start fighting back and then it’s the holiday-makers who get slaughtered. Westworld, in fact, is a prototype for Jurassic Park, with the same theme-park setting but with robots instead of dinosaurs as the exhibits-that-turn-nasty.

From wikipedia.org / © Jon Chase, Harvard News Office

I knew Crichton’s novel would get trimmed as it was turned into a film, but I was dismayed at how much of it was trimmed. While Jaws shed a few gratuitous sub-plots that’d made its source novel, the 1974 bestseller by Peter Benchley, seem flabby, and it was a lean, muscular movie as a result, Spielberg’s Jurassic Park was pared to the bone. In its final reel the park’s pack of deadly velociraptors have escaped from their compound, the surviving humans are running around trying to avoid being eaten by them, and that’s about it. The velociraptors rampage through the book’s final chapters too, but there are other matters adding to the suspense. It becomes clear that some velociraptors have managed to board the supply-ship that services the island where the park is located, and there’s a real danger that they’ll reach the American mainland and become an ultra-lethal invasive species. The humans are also on a desperate quest to count the hatched eggs in the velociraptors’ nests, so that they can calculate just how many of the scaly killers are on the loose.

Also simplified are the fates of the characters. The main characters, palaeontologists Alan Grant and Ellie Sattler, chaos theorist Ian Malcolm and the billionaire mastermind behind the park, John Hammond, don’t all make it to the end of the book. Malcolm expires from injuries sustained from a dinosaur attack while Hammond dies after he hears the roar of a tyrannosaurus rex, panics and falls down a hillside. (Ironically, the roar comes from the park’s PA system – Hammond’s two young grandchildren have been mucking around in a control room with some dinosaur recordings.) Meanwhile, certain secondary characters, like the park’s lawyer Gennaro and its game warden Muldoon, survive the dino-carnage. Gennaro is even allowed to show a degree of courage, which is unusual for a fictional corporate lawyer.

In the movie, though, Grant, Sattler, Malcolm and Hammond are played by big-name stars – Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum and veteran British actor / director Sir Richard Attenborough – who clearly had it in their contracts that none of them would suffer the indignity of being eaten by a dinosaur. So, they all survive. But because this is a monster movie, which demands that monsters eat people at regular intervals, the supporting characters are gradually bumped off, including Gennaro and Muldoon. This makes the plot very predictable. Interestingly, one supporting character who got killed in the book but made it out of the movie alive is the geneticist Henry Wu. Played by B.D. Wong, he’s ironically become the character with the most appearances in the Jurassic Park franchise – Wu’s now turned up in four of the movies.

Meanwhile, the casting of Attenborough symptomizes one of the film’s worst features. The cuddly, twinkly Attenborough, who one year later would play Santa Claus in a remake of Miracle on 34th Street, is way nicer than the John Hammond of the book, who’s a callous, conniving and delusional arsehole. He should have been played by Christopher Lee or Donald Pleasence.

© Universal Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Spielberg couldn’t bring himself to be nasty to Hammond, whom he probably regarded as a kindred spirit. Hammond at his dinosaur theme park, like Spielberg in Hollywood, is merely trying to wow the masses by giving them spectacles they haven’t seen before. How could he be bad? Thus, we get a maudlin scene where Hammond explains his motives to Dern’s character by reminiscing about his first venture in the entertainment business – a flea circus. (Attenborough also gives Hammond the worst Scottish accent in movie history, so he tells Dern how he brought his wee flea circus “doon sooth frae Scotland” to London.) Look how big the fleas are in his circus now, Spielberg seems to tell us. What a visionary!

The softening of Hammond’s character infects the rest of the film. Though some of the velociraptor and tyrannosaurus-rex scenes are scary, it’s all a bit too feel-good. Spielberg wants us to be awed by the dinosaurs, not shit ourselves at them. John Williams’ musical score adds to the problem – his Jurassic Park theme, according to Billboard magazine, oozes with ‘astonishment, joy and wonder’; but since this is supposedly a sci-fi horror movie, shouldn’t it be oozing with some old-fashioned fear too?

But my biggest frustration about the film was that while Spielberg portrays Hammond as being like Walt Disney, the park isn’t like Disneyland – and it ought to be. In the novel Crichton wonderfully juxtaposes the primeval and the high-tech. There might be hordes of monstrous reptiles from earth’s distant past stumping around the wilds of Hammond’s island, but at the same time the place bristles with state-of-the-art sensors and cameras and is honeycombed with service tunnels crammed full of power-cables. At its centre is Hammond’s console-packed control room where he squats like a space-age spider in a technological web. The joy of the book is watching all this technology slowly, gradually start to malfunction and break down – until finally it’s useless. And meanwhile, the prehistoric stars of the show are clawing at the scenery, hungry to get at the humans who’ve been pulling the levers behind it.

You don’t really get this impression in the film. Attenborough’s control room looks a bit dingy, like he’s set it up in his garden shed. And the dinosaurs just seem to be out in big fields with big fences around them – nothing in the background but foliage, nothing underneath but soil. This Jurassic Park is more like Jurassic Farm.

No, while I sat through Jurassic Park in a cinema 22 years ago, I didn’t feel like I was watching a classic. The main thing I felt was a huge sense of disappointment – crushing me as effectively as if one of the behemoths onscreen had suddenly stepped out into the auditorium and trod on me. For the authentic Jurassic Park thrill-ride, check out Crichton’s book.

© Alfred A. Knopf