© Crimson Quill Quarterly

My sword-and-sorcery story The Voice of the River is now available to read in Volume 9 of the magazine Crimson Quill Quarterly, which was published at the end of last month. As with all my fantasy fiction, it’s attributed to the pseudonym Rab Foster.

Someone once observed – it might have been Stephen King in his forward to his 1978 collection Night Shift – that a writer’s mind is like the grating on a storm drain. Just as water flows in through a real grating and the bigger debris it carries gets stuck there, so a writer’s mental grating gets clogged with ideas, impressions and images while his or her life-experiences seep through it – all things that can inspire or be incorporated into stories. The gunk trapped in my grating, from which I fashioned The Voice of the River, contained some disparate things indeed.

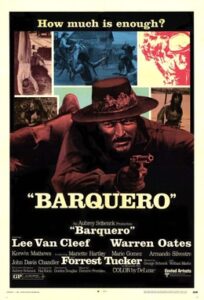

When I was 11 or 12 years old, I watched a western on late-night TV called Barquero (1970). I assumed at the time it was a spaghetti western, because Lee Van Cleef was in it, but since then I’ve discovered it was an American movie directed by the prolific Gordon Douglas, whose best-remembered film is probably the giant-ants-on-the-loose sci-fi / horror classic Them! (1954). The cast also included Warren Oates, Forest Tucker and Kerwin Matthews, so I should have twigged onto Barquero’s American-ness sooner. Anyway, as Van Cleef’s character was a river ferryman, who gets caught up in shenanigans with some bandits, and as I’d recently been reading Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian stories, I suddenly had an idea: Wow, what if Conan retired from being a barbarian and took up a supposedly easier job, running a barge that ferried people across a river?

The notion sank to the back of my head and remained dormant for several decades – until last year, in fact, when I read Cormac McCarthy’s Outer Dark (1968), which contains an episode set on a river ferry. That reminded me of my long-ago idea about ‘Conan the Ferryman’ – though I realised an unruly, adventure-loving character like Conan would balk at such a job. So I modified the premise to ‘a sword-and-sorcery story involving a river ferry’.

Other debris stuck in that mental grating, also from movies, gave me inspiration for the story’s characters. I’ve long been interested in the late Northern Irish character actor John Hallam, who appeared as hard men and coppers in a string of 1970s British crime movies – Villain (1971), The Offence (1972), Hennessey (1975) – though he’s maybe best-known for playing Luro, Brian Blessed’s winged sidekick in Flash Gordon (1980). I visualised The Voice of the River’s main character as being like the tall, gangly, craggy Hallam and took his name, Halym, from the actor’s surname. Meanwhile, both the appearance and personality of another character in the story were inspired by Peter Cushing in the role of Gustav Weil, the fanatical anti-hero of one of my favourite Hammer horror movies, 1972’s Twins of Evil.

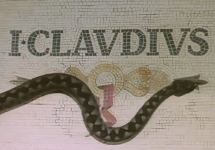

© BBC / London Films

Finally, The Voice of the River pays tribute, sort of, to a scene from a TV show that’s always haunted me. It comes at the end of the final episode of I, Claudius (1976), the BBC’s acclaimed adaptation of Robert Graves’s novels I, Claudius (1934) and Claudius the God (1935), when Claudius (Derek Jacobi), on his deathbed, has a conversation with a supernatural entity – the oracle the Sybil (Freda Dowie), who’s come to usher him to the River Styx and the underworld. I love how, though one is flesh-and-blood and the other is ethereal, they speak as equals and both have seen so much of the world that they’re weary of it. (“It all sounds depressingly familiar,” Claudius sighs after the Sybil has told him what will happen to Rome after his death. “Yes,” she replies, “isn’t it?”) I tried to replicate a little of that magic in this newly-published story.

So, The Voice of the River owes its genesis to a 1970 Lee Van Cleef western, Cormac McCarthy, a tough Northern Irish character actor, some Hammer horror villainy by Peter Cushing and I, Claudius. Not bad for a simple sword-and-sorcery tale.

One thing about Crimson Quill Quarterly that impresses me is the time and effort its editors spend on the editing process – including consulting and reconsulting the writers of its stories about suggested improvements – to ensure that the fiction in its volumes is in its best possible form when they go on sale. Containing seven stirring tales of fantasy, magic and derring-do, its ninth edition can be purchased here.

© United Artists