© Channel 4 Films / PolyGram Filmed Entertainment

Hot on the heels of my post about Robert Burns, here’s the latest in my series about favourite words in Scots, the language Burns wrote in. Many Scots words begin with the letter ‘S’, so in this instalment I’m only going to list the first half of them.

Scaffy (n) – not, as you might expect, a scaffolder, but a streetcleaner or binman.

Scheme / Schemie (n) – a scheme is the Scottish word for a housing estate and schemie is the derogatory word for someone who lives on one. One long-ago Saturday evening, while I was wandering around central Edinburgh, I went past a nightclub and was suddenly accosted by an upset young woman who demanded, “Dae I look like a schemie?” Her supposed resemblance to a schemie was why the bouncer at the nightclub door had just turned her away.

Meanwhile, a much-quoted line from Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1993) comes from Mark Renton when he turns up for a job interview: “They’d rather gie a merchant school old boy with severe brain damage a job in nuclear engineering than gie a schemie wi a Ph. D. a post as a cleaner in an abattoir.”

Scooby (n), as in ‘I havenae a Scooby’ – rhyming slang for ‘clue’. Scooby refers to Scooby Doo, the famous American TV cartoon dog who first appeared in 1969, accompanying some ‘meddling kids’, without whose investigations many, many, many criminals “would have gotten away with it.” I’ve seen arguments online about whether this started as Scottish rhyming slang and then spread to England, or started as Cockney rhyming slang and spread to Scotland. But I’m sure I heard it in Scotland back in the 1980s, and it was appearing in Scottish newspapers in the 1990s, so its Caledonian pedigree is pretty venerable.

Scrieve (v) – to write. Accordingly, a scriever is a writer. “Just been doin’ a wee bit scrievin’ you know,” says Matt Craig, the main character and aspiring scriever in Archie Hind’s Glasgow-set novel The Dear Green Place (1966), which is as good an account of the trials and tribulations facing a working-class person trying to make a name as a writer, and a living from it, as Jack London’s better-known Martin Eden (1909).

© Corgi Books

Scunnered (adj) – sickened or disgusted. During the 1980s and 1990s, this word was commonly used in Scotland on the mornings following general elections, when it became clear that a majority of people in Scotland had voted for the Labour Party and a majority of people in the south of England had voted for Maggie Thatcher’s Conservatives. Guess who ended up ruling Scotland each time? For a 21st-century variation on this, see the Brexit vote.

Sharn (n) – dung. Yes, Dungeons & Dragons enthusiasts may know Sharn as a city that ‘towers atop a cliff above the mouth of the Dagger River in southern Breland’ in the fictional world of Eberron, but in Scots sharn refers to cow-shite. That’s a warning to fantasy creators. When you dream up names for your fantasy characters, creatures and places, be sure to check they don’t also mean something embarrassing in Scots. Now please excuse me while I get back to writing my latest sword-and-sorcery epic wherein Glaikit the Barbarian rescues Princess Jobbie from the clutches of the Dark Lord Pishy-Breeks in the Kingdom of Boak.

Shauckle (v) – to shuffle along, barely raising your feet off the ground.

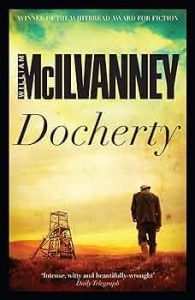

Sheuch (n) – a channel for removing wastewater, i.e., a gutter at the side of a street or a ditch at the side of a field. In William McIlvanney’s 1975 novel Docherty, the young hero Conn gets battered by his school’s headmaster for saying to him, “Ah fell an bumped ma heid in the sheuch.” The fact that he doesn’t use the ‘correct’ word, gutter, is seen as ‘insolence’. Early in the 20th century, when the events of Docherty take place, Scottish schoolkids would be punished for using Scots rather than the King’s English. The only day in the year when Scots was acceptable in schools was January 25th, Robert Buns’ birthday, when they were made to recite the poetry of their national bard.

© Canongate Books Ltd

Incidentally, in Northern Ireland, where I spent my childhood, a sheuch seemed to be only a ditch. My dad was a farmer and once or twice I heard him cry, “There’s a cow got stuck in the sheuch!” And the North Channel – the strip of water above the Irish Sea that separates Scotland and Northern Ireland – was called ‘the Sheuch’ and the land-masses east and west of it termed ‘baith sides o’ the Sheuch.’

Shieling (n) – a hut or shelter for animals, usually out in the wilds and / or up in the hills.

Shilpit (adj) – thin, pale and weak-looking.

Shoogly (adj) – wobbly. To hang on a shoogly peg means to be in dodgy, precarious or dire circumstances. Since the arrival of the ineffectual and accident-prone Humza Yousaf as First Minister of Scotland, it’s fair to say the peg the electoral fortunes of the Scottish National Party hang on has been pretty shoogly.

Skean–dhu (n) – the Anglicised (or Scotticised) version of the Gaelic term sgian-duhb, meaning the ceremonial dagger that’s tucked behind the top of the hose in male Highland dress. Considering the popularity of Highland dress at Scottish weddings, and the amount of alcohol consumed at them, it’s always surprised me that the country has avoided having a sky-high death-toll of wedding guests stabbed with skean-dhus in drunken altercations.

From wikipedia.org / © Stubborn Stag

Skelf (n) – a splinter.

Skelp (n / v) – to slap or a slap. Skelps were often administered by parents and teachers to wayward kids back in the days, fondly remembered by the Daily Mail and Daily Express, when it was believed that assaulting children was good for them.

Skite (n / v) – also to strike someone or the blow thereof. However, a skite is more likely to come from a sharp, stinging cane or stick than the open hand that delivers by a skelp. Both are nicely onomatopoeic words, in their different ways.

Skoosh (n / v) – a squirt or spray of liquid. A commonly heard exchange in Scottish pubs: “Dae ye want water in yer whisky?” “Aye, but just a wee skoosh.”

Sleekit (adj) – according to the Merriam Webster dictionary, either ‘sleek’ and ‘smooth’ or ‘crafty’ and ‘deceitful’. Presumably it was with the first meaning that this word got immortalised in a line of Robert Burns’ 1785 poem To a Mouse: “Wee, sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie…” Nowadays, it’s used mainly with the ‘crafty’ and ‘deceitful’ application. I can think of many politicians I’d describe as sleekit, but I won’t mention any names.

Smeddum (n) – in physical terms, a powder. However, smeddum has also come to mean the kernel or essence of something, and presumably from that to mean its vigour, spirit, determination or grit too. Robert Burns – him again – had the first meaning in mind when he wrote about ‘fell, red smeddum’, possibly referring to red precipitate of mercury, in his 1785 poem To a Louse. Whereas Lewis Grassic Gibbon was thinking of smeddum’s spiritual denotation when he made it the title of his most famous short story, about a hard-working Scottish matriarch called Meg Menzies who takes no shit from anyone. As Meg herself says: “It all depends if you’ve smeddum or not.”

Smirr (n) – a drizzly rain falling in small droplets. This sad, ghostly word perfectly describes the sad, ghostly semi-rain that sometimes seems to envelop Scotland’s landscapes 365 days of the year.

Snaw (n) – snow. Like snaw aff a dyke is a simile commonly used to describe something that disappears, or is disappearing, super-fast: for example, jobs for life, polar icecaps, cashiers in supermarkets, CD and DVD drives in laptops, Twitter’s credibility after Elon Musk took it over, and Liz Truss premierships.

© Canongate Books Ltd