© Warner Bros.

I’ve just discovered that a few days ago was the 80th birthday of the film and TV character actor David Warner. In honour of the great man becoming an octogenarian, here’s an updated version of a post I wrote about him eight years ago.

For most actors, becoming typecast is a pain in the neck. The day that the lugubrious-faced, distinctive-voiced David Warner became typecast, as an actor specialising in offbeat roles in offbeat films, often horror, science fiction and fantasy ones, it was actually a pane in the neck.

As Keith Jennings, the photographer who befriends Gregory Peck’s ambassador Richard Thorne in 1976’s The Omen, he is memorably decapitated when a sheet of glass comes crashing off the back of a truck and shears his head from his shoulders. Indeed, though The Omen was choc-a-block with people dying in gruesome freak accidents, and later there were Omen sequels with more freak accidents, and later still there were a half-dozen Final Destination movies following a similar template and serving up many more freak accidents, the cinema has seen very few freak accidents as spectacularly shocking as Warner’s in that 45-year-old movie.

© 20th Century Fox

The main actors in the big-budget Omen – Peck, Lee Remick, Billie Whitelaw – were names not normally associated with horror movies. Until then, Warner’s name hadn’t been associated with them either. Mancunian by birth, he started acting professionally in 1962 and the following year joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, which led to stage roles in Henry IV Part 1, Henry VI Parts I-III, Julius Caesar, Richard II, The Tempest, Twelfth Night and, in 1965, playing the title role, Hamlet. The earliest films he appeared in were sometimes theatrical in origin too, such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Sea Gull, which both appeared in 1968. However, it was in 1966’s Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment that he made his biggest impression on 1960s movie audiences. In it he plays a working-class artist who’s abandoned by his posh wife, played by Vanessa Redgrave, and goes to unhinged extremes to win her back.

When Warner’s career is discussed, it’s often overlooked that he was once a regular performer with the legendary action-movie director Sam Peckinpah. His association with the hard-drinking, coke-snorting, near-deranged filmmaker started with 1970’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue, in which he played an eccentric preacher who befriends Jason Robards’ titular hero. Peckinpah often boasted, “I can’t direct when I’m sober,” and for the young Warner Hogue must have been quite an initiation into the director’s weird and wonderful ways. When bad weather held up filming, Peckinpah and his crew went on a massive drinking binge and ran up a bar-bill worth thousands and thousands of dollars.

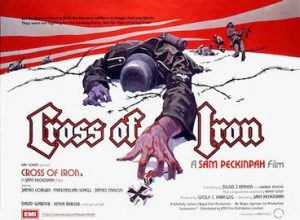

In the next year’s Straw Dogs, Peckinpah’s taboo-busting film set in the English West Country, Warner plays a simpleton who unwittingly kills a girl and then takes refuge in Dustin Hoffman and Susan George’s house with a squad of vigilantes on his trail. In Cross of Iron, Peckinpah’s 1977 war movie about a doomed German platoon on the Russian front, he plays a humane German officer who just wants to get through the war in one piece. In fact, in Cross of Iron, nearly all the Germans, including James Coburn’s gallant corporal and James Mason’s world-weary colonel, are humane types who view war with extreme distaste. What upsets the apple-cart, and eventually gets most of them killed, is the arrival of Maximillian Schell’s glory-hunting Prussian officer. Schell is obsessed with winning an iron cross for himself and isn’t worried about other soldiers dying in the process.

© Anglo-EMI Productions

In 1973 Warner made his first appearance in a horror film, the British anthology movie From Beyond the Grave, whose stories were based on the writings of Ronald Chetwyn-Hayes. In the film’s first story, The Gate Crasher, he plays an arrogant prick called Edward Charlton who acquires an old mirror from an antique shop and gets it on the cheap by lying to the shop-owner about the mirror’s likely age. Charlton obviously hasn’t seen many horror films before. Otherwise, he might have thought twice about cheating a proprietor played by Peter Cushing in a shop called Temptations Inc. He gets his just deserts. The mirror turns out to be inhabited by a malevolent spirit, which possesses him and drives him to commit murder.

It was in the late 1970s and early 1980s that Warner got his fondest-remembered roles, starting with the kindly but ill-fated Jennings in The Omen. Then, in 1979’s Time After Time, he switches from being a nice guy to being a bad one, playing John Leslie Stevenson, a Victorian gentleman and friend of the pioneering science-fiction writer H.G. Wells, who’s played by Malcolm McDowell. Unbeknownst to Wells, Stevenson has been making a name for himself by butchering prostitutes in Whitechapel – for he is none other than Jack the Ripper. When Wells unveils his latest invention, a working time machine like the one he would later write about in his famous 1895 novella, Stevenson uses it to escape the closing police net and scoots one century forward into the future. But the machine has a recall function, so a horrified Wells summons it back to the 19th century and uses it to follow Leslie to 1979. Wells assumes that he’s let Jack the Ripper loose on Utopia and, predictably, is more than a little disappointed to find that the 20th century is less utopian than he’d anticipated. Meanwhile, the Ripper has taken to the era’s violence, sleaze and heavy-decibel rock music like a duck to water.

A quirky and very entertaining movie, Time After Time was written and directed by Nicholas Meyer who, regrettably, devoted most of his energies to the less adventurous and eccentric, and more mainstream and family-friendly Star Trek franchise during the 1980s. Actually, it’s probably because of Meyer’s involvement that both Warner and Malcolm McDowell have made appearances in Star Trek films – Warner was in both Star Trek V and VI (1989 and 1991). I’m not much of a fan of Star Trek or its movie spin-offs, but I like the sixth one, largely because Warner is in it. He plays Chancellor Gorkon, charismatic leader of the Klingons and obviously modelled on the then Soviet leader Mikael Gorbachev, who’s decided it’s time for the Klingon Empire to pursue peace-talks with the Federation.

In 1981 Warner delivered another memorable performance in Terry Gilliam’s cinematic fairy tale The Time Bandits. He plays Evil, who’s been created by Ralph Richardson’s Supreme Being and then imprisoned in a hellish place called the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness. Obviously, Warner and Richardson’s characters are the Devil and God under different monikers. Some fine actors have played Old Nick in movies over the years, including Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Jack Nicholson, but for my money Warner’s portrayal is the most entertaining. His Devil is a petulant and embittered type who spends his time ranting at his idiotic minions (“Shut up! I’m speaking rhetorically!”) about how rubbish God is. The Almighty, he argues, has wasted His time creating useless things such as slugs, and nipples for men, and 43 species of parrots, when He could have concentrated on making laser beams, car phones and VCRs. Warner steals the show in The Time Bandits, which is no minor achievement considering that in addition to Richardson the film stars Ian Holm, John Cleese, Sean Connery, Michael Palin, Shelley Duvall and a delightful gang of time-traveling dwarves led by David Rappaport.

Thereafter, Warner’s CV filled with all manner of odd movies, hardly Shakespearean in the acting opportunities they offered, but relished by obsessives like myself. These include 1979’s Nightwing, 1980’s The Island, 1987’s Waxwork, 1991’s Cast a Deadly Spell, 1995’s In the Mouth of Madness, 1997’s Scream 2 and 2010’s Black Death.

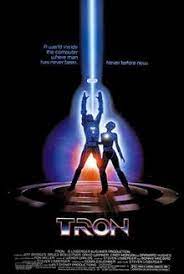

© Walt Disney Productions

As an actor he’s adept at playing out-and-out villains, for example, his Dillinger / Sark character in the 1981 Disney computer-game fantasy Tron, a movie that was unappreciated at the time but that, in the decades since, has been accorded considerable retro-cool. He’s also good at doing mad scientists, like the splendidly named Doctor Alfred Necessiter in the whacky 1982 comedy The Man with Two Brains, which is poignant today as a reminder of the time when Steve Martin used to be funny.

But he also has harassed and melancholic qualities, which come nicely to the fore when he’s playing fathers. He was, for instance, the heroine’s father in 1984’s The Company of Wolves, Neil Jordan’s atmospheric and sensual adaptation of Angela Carter’s gothic short stories. Meanwhile, in Tim Burton’s 2001 remake of Planet of the Apes, he plays Senator Sandar, father of dishy chimpanzee Helena Bonham-Carter. In heavy simian make-up and in Warner’s unmistakable tones, Sandar sighs at one point: “Youth is wasted on the young…”

In 1997 Warner found time to appear in James Cameron’s Titanic, then the biggest-grossest movie of all time. Say what you like about Titanic, about the mawkish love story between Kate Winslet and Leonardo Di Caprio, about Billy Zane’s cartoonish performance as the villain, about the unspeakable theme song sung by Celine Dion, but you can’t deny that it has a great supporting cast: Warner, Kathy Bates, Bernard Hill, Victor Garber, Bill Paxton. Warner, playing Spicer Lovejoy, Zane’s valet, doesn’t have much to do apart from connive with his master, stalk around, spy on Kate Winslet and generally behave sinisterly. He does, though, get to punch Di Caprio in the guts after he’s been handcuffed to a railing on board the sinking liner, which is actually my favourite bit in the film. (Warner also turned up in a 1979 movie called SOS Titanic and the Titanic features in The Time Bandits too. Thus, he’s a titanic actor in all senses of the term.)

Warner has long been a fixture on television as well. He’s appeared in one-off TV movies and dramas like 1984’s Frankenstein, where he plays the creature to Robert Powell’s Victor Frankenstein and Carrie Fisher’s Elizabeth, 1993’s Body Bags and 2003’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; appeared in series and mini-series like 1981’s Masada, 1982’s Marco Polo, 1984’s Charlie, 2011’s Secret of Crickley Hall and, from 2008 to 2016, Wallander, in which he plays another father, this time to Kenneth Branagh; and lent his voice to animated shows, including the Superman, Batman and Spiderman ones during the 1990s.

© Greengrass Productions / ABC Distribution Company

Some of his TV work is as cult-y as his film work. In 1991, he guest-starred in three episodes of David Lynch’s glorious, off-the-wall crime / horror / sci-fi / soap opera Twin Peaks, playing Thomas Eckhardt, a Hong Kong-based crime-lord who has a long and dark history with Joan Chen’s Jocelyn Packard. Two years after that, he appeared in the underrated, Oliver Stone-produced mini-series Wild Palms, a hybrid of conspiracy thriller, Alice in Wonderland and the then-recent literary genre of cyberpunk. Set in a near-future USA, under the heel of an organisation that’s part multinational corporation and part Scientology-style religious sect, the show features Warner as Eli, the leader of an underground resistance movement. (This clip neatly encapsulates Wild Palms’ weird energy.) And in 2014 he popped up in John Logan and Sam Mendes’ gothic horror mash-up Penny Dreadful, in the role of Bram Stoker’s vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing. Because Warner played Frankenstein’s creature in 1984, it’s ironic that in Penny Dreadful – in a cheeky tangling of Stoker and Mary Shelley’s original narratives – Van Helsing gets killed by the same creature, played this time by Rory Kinnear.

In 2005 Warner was involved with the macabre TV comedy show The League of Gentlemen, written by and starring Mark Gatiss, Reece Shearsmith, Steve Pemberton and Jeremy Dyson. In fact, he didn’t appear in the show itself, but in its cinematic spinoff The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse. Like many a film-based-on-a-TV-show, it doesn’t really work on the big screen, though its most effective scenes are definitely those featuring Warner as a 17th century magician called Dr Erasmus Pea. His character is rottenly evil but he’s very amusing too. For example, while Dr Pea uses a pan to fry a hellish concoction including two recently gouged-out eyeballs, from which he plans to grow a monstrous homunculus, the camera cuts to a close-up and he pulls a pretentiously absorbed, TV-chef expression worthy of Jamie Oliver.

Warner clearly gets along with The League of Gentlemen’s creators, because since then he has appeared alongside Mark Gatiss in the radio comedy show Nebulous (2005-8); in The Cold War, a 2013 Gatiss-scripted episode of Doctor Who; and in The Trial of Elizabeth Gadge, a 2015 episode of Reece Shearsmith and Steve Pemberton’s acclaimed anthology show Inside No. 9.

The 21st century has seen Warner return to the stage, giving well-received turns as the venerable and vulnerable monarch in King Lear in 2005 and as Falstaff in Henry IV Parts I and II in 2007. His IMDb entry lists his most recent movie appearance as 2018’s Mary Poppins Returns and says he was still doing voice-work last year. Warner is now at an age where you wouldn’t begrudge for him retiring and choosing an easier life of armchairs, cardigan, slippers and pipe, but I for one hope that some young filmmakers – perhaps ones who grew up enjoying his performances in The Omen, Time After Time, The Time Bandits and Tron when they were shown on TV – coax him into making a few more movies. He’s the sort of actor whose mere presence in a film, no matter how good or bad, gives you a glow.

© Handmade Films / Janus Films