Halloween is almost upon us, so this is an appropriate time to post an account of what happened when my partner and I, plus a friend, went on a ghost tour around Fort Canning.

Fort Canning is both a 48-metre-high hill in Singapore’s bustling Central Area and a park with a range of recreational facilities and historical landmarks and a lot of pleasant greenery. To be honest, we didn’t go on a fully-fledged ghost tour. It was advertised as The Fort Canning Conspiracy Tour. Our guide also talked about rumours, reports and whisperings from the place’s past that concerned such Dan Brown-esque things as buried kings and treasure, curses – it was known at one point as the Forbidden Hill – and colonial-era secrecy and skullduggery involving the British. But along the way, we also heard plenty of stories about ghosts, superstitions and the weird and unexplained. And, generally, we had a great deal of fun.

The tour’s participants met up at 6.30 PM at the entrance of Singapore’s lovely Peranakan Museum on Armenia Street. Our guide introduced himself as Eugene Tay, who’s an author (his book Supernatural Confessions: You are not Alone was published in 2015), the founder of the tourism group Haunting Heritage Tours, a YouTuber, a podcaster and, according to the online Singaporean / Malaysian publication Vulcan Post, ‘the only licenced tour guide in Singapore running ghost tours.’ For this evening’s tour he had five people in his party. He began by asking each of us to introduce ourselves and say why we had an interest in the esoteric and paranormal. No sooner had I mentioned my Irish roots than one of the other tour-members, a Singaporean, asked me about ‘leprechauns’. I retorted that Ireland’s leprechaun industry is mainly aimed at gullible American tourists. Five seconds after I said that, I remembered my beloved better-half, standing next to me, is American.

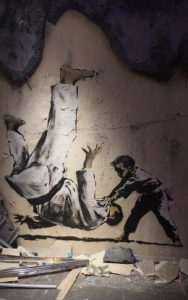

We kicked off by hearing some stories about the Tao Nan School building – the handsome old structure that houses the Peranakan Museum – and the Substation, the currently derelict building next door to it that, for a few decades, was home to ‘Singapore’s first independent contemporary arts centre’. (A remnant of the Substation’s past glories is the message “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable’, graffitied on a boarded-up window.) These involved staff-members in both buildings having weird experiences and encountering inexplicable figures at times when there shouldn’t have been anyone there.

Standing outside the museum entrance are statues of a man and a little girl, the girl waving up at a balcony on the museum’s façade. I got a jolt when I glanced up at the balcony and spotted a spectral figure there, standing within an archway. Really, though, it was just another statue, of an old lady waving down at the girl. It was still daylight, but Eugene’s tour was evidently starting to unsettle me.

Then we went around the corner onto Hill Street and into the grounds of the Armenian Church of St Gregory the Illuminator. This was consecrated in 1836 as a place of worship for Singapore’s members of the Armenian Apostolic Church and was designed by the architect George Drumgoole Coleman – responsible for many of Singapore’s early colonial buildings and a name that would crop up again on the tour. From a ghost-tour point of view, its eeriest feature is the Memorial Garden at the rear of the grounds, where there are tombstones, graveyard monuments and ledger stones arranged in two semi-circles, one horizontal, one vertical. They were moved here from the Christian Cemetery at Fort Canning when it was cleared to make a park, and also from the Bukit Timah-Cavenagh Road Cemetery. (The human remains weren’t moved.)

As the dusk gathered, the elaborately sculpted headstones and stone statues gave the location an atmospheric vibe. Supposedly, their arrival here inspired some creepy stories about taxi drivers picking up folk outside the church late at night, being asked to drive the passengers to certain disused cemeteries around Singapore… and, when they got to their destinations, discovering that those passengers had mysteriously vanished from the back of their cabs. Though such tales obviously riff on the old urban myth of the ‘vanishing hitchhiker’. Incidentally, it was nice that the church’s supervisor joined us at this point and answered our questions about the building and its history.

From there, we went around another corner into Canning Rise and ascended past Singapore’s Masonic Hall – Freemasonry was brought here by the British – and then the National Archives building, which was previously the site of Singapore’s prestigious Anglo-Chinese School. At both places, we stopped and heard more tales. We heard the first mention of conspiracies. What had the Freemasons been up to in the the 19th century? And, though their original number contained such prestigious figures as Stamford Raffles, founder of contemporary Singapore, and William Napier, its first lawyer, why wasn’t the architect who did so much to fashion the early city, George Drumgoole Coleman, invited to join them? We’d hear more speculation about that later. Then we entered the park itself – through the Spice Garden, to the edge of Fort Canning Green, and up to Cox Terrace behind the majestically floodlit Fort Canning Centre. By now it was fully night-time.

Rather than do all the talking, Eugene handed out cards with printed testimonies by people who’d had frightening and baffling experiences in the vicinity and encouraged his tour-members to read them aloud. Among the stories I read out was one from a person who, as a child, had encountered a strange Western figure at Fort Canning’s old cemetery. The figure lamented, “I shouldn’t have brought her here! I should never have trusted him!” and then disappeared by the grave of George Drumgoole Coleman. In fact, Coleman married an Irishwoman in 1842, brought her to Singapore in late 1843 – and died just three months later from an alleged ‘fever.’ And within seven months of that, his wife had married the lawyer William Napier. Which all sounds a bit fishy.

Meanwhile, the friend we’d brought with us, a sometime-actress, added to the mood by embellishing her readings with truly blood-curdling cackles.

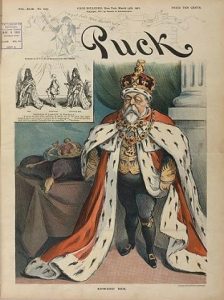

Also in the park, we got a look at Kermat Iskandar Shah, a wooden pavilion with a tiled roof that was once a shrine. It’s associated with Parameswara, who was supposedly the fifth and final king (Raja) of Singapura, the kingdom believed to have existed here during the 13th and 14th centuries. At the very end of the 14th century, Parameswara had to flee when the Majapahit Empire launched an invasion. He ended up further north along the Malay Peninsula, at the mouth of the Bertram River, and founded what is now Malacca. Kermat Iskandar Shah has been claimed to be Parameswara’s burial place, but this doesn’t make sense if he really did escape the island and re-establish himself in the future Malacca.

Indeed, there are stories about all five kings of Singapura being buried under the hill, which raises questions about what treasures and riches might have been buried with them. (Archaeological excavations have taken place near the pavilion, but according to Wikipedia they mainly uncovered Chinese coins and porcelain fragments from the Tang Dynasty.) I wondered if this was why the place was once known as the Forbidden Hill where, supposedly, trespassers were cursed and would die. Was it a strategy to frighten off potential tomb-robbers?

When Stamford Raffles arrived in 1819, he may have heard about the curse. Rather than go up Fort Canning himself, he cannily sent Scotsman Major William Farquhar up it first, along with some Malays, to plant a gun and the Union Jack at its top. When Farquhar arrived back in one piece, Raffles evidently decided it was safe and subsequently had Coleman design him a bungalow to live in atop the hill, which was completed in 1823. Eugene observed that perhaps some bad karma from the place did rub off on Raffles because, back in England, he died when he was only 45. (Farquhar, on the other hand, outlived his old boss by 20 years.) He also noted that the British did a lot of mysterious digging on the hill. Were they secretly trying to locate the treasures of Singapura’s former kings?

We got a look too at the outside of the Battlebox, officially known as the Fort Canning Bunker or the Headquarters Malaya Command Operations Bunker. Here, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, Commander of the British Commonwealth forces, and 500 officers and men holed up after the Japanese attacked Singapore in 1942. Percival ended up surrendering, an event Winston Churchill described as ‘the worst disaster and biggest capitulation in British history’. Subsequently, the Japanese, the new, if temporary, masters of Singapore, took over the Battlebox. However, they didn’t stay there long and vacated it again. Could this have something to do with supernatural goings-on deep in the bunker? No. According to Eugene, the Japanese didn’t like it because the British had left it like a pigsty.

What I enjoyed most about this tour was its improvisational nature. Tour-members and even passers-by were welcome to contribute. At the National Archives building, the former Anglo-Chinese School, one of our party mentioned that he’d been a pupil there when it’d been a school… And he’d had a spooky experience on its third floor. The building was still open, so Eugene took us in, we went up to the floor, and the man told us what’d happened to him at the actual location. He’d been alone in a music room when the air around him had inexplicably turned cold. Later, he’d heard that the room was supposed to be haunted. Wonderfully, the building’s security guard, noticing us, insisted on telling us about a creepy, inexplicable experience he’d had there, doing his rounds, a few years earlier.

Later, when we were passing through the old Fort Canning Gate, an elderly gentleman out for a walk approached us. He’d recognized Eugene from his YouTube videos and wanted to tell us about an evening when he’d seen a ghostly figure near that spot.

Many more stories later, we found ourselves descending the far side of the hill, towards Fort Canning MRT Station. As Eugene finished up, we heard the eerie creaking of a swing in a nearby playground. While it cranked back and forth, I nervously looked towards it. First, I was relieved to see a human figure using the swing. Then I realized it was a female figure whose face I couldn’t see, but who had long black hair – like a character from a Japanese horror movie. And, momentarily, I was supremely spooked.

Another sure sign this tour had been a success.