© Triad Granada

Recently, I’ve read a couple of ‘alternative history’ novels that imagine different realities in the 1930s and 1940s: wherein Britain and the USA were taken over by fascism just as Germany and Italy were. What could have induced me, in 2025, to read novels about Britain and the USA succumbing to fascism? I really can’t imagine. Here are my thoughts on one of those books, Len Deighton’s SS-GB (1978).

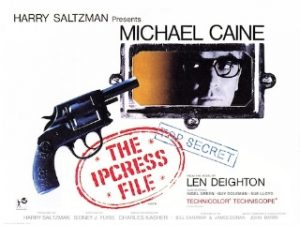

Deighton is best known as the author of The IPCRESS File (1962), the book that introduced the world to Harry Palmer, a down-at-heels spy whose humdrum experiences are a corrective to the glamorous espionage fantasy-world inhabited by Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

Actually, that description does both Deighton and Fleming a disservice. Harry Palmer isn’t even the name of the protagonist in The IPCRESS File. Deighton keeps its first-person narrator anonymous. The name was only devised for the character in 1965 when the book was made into a film with the non-capitalised title The Ipcress File, directed by Sidney J. Furie and starring Michael Caine. Also, while the film version is determinedly unexotic and, possibly for budgetary reasons, restricts its action to a non-swinging 1960s London, Deighton’s novel is more expansive. It allows its hero to do some properly exciting, Bondian things, such as participate in a rescue mission in Beirut and visit an American neutron-bomb test site in the Pacific Ocean.

Meanwhile, Fleming’s novels certainly featured exotic locations (the Caribbean, the Swiss Alps, the French coast), exotic activities (scuba diving, skiing, gambling in casinos) and exotic food and drink (caviar, stone crabs, Dom Pérignon champagne), which no doubt tantalised his readers, many of whom were living in drab, austere, post-war Britain and eating such rationing-era fare as pig’s trotters, spam and lardy cake. But he invested at least some of those novels with a little grit and realism too. However, just as the medium of film made Harry Palmer more lowkey than the literary original, so a series of over-the-top movies unanchored the character of Bond and floated him off into the realms of total fantasy. Ironically, the Harry Palmer movies and the first nine Bond movies shared the same producer, Harry Saltzman.

© Lowndes Productions / Rank Film Distributors

I was reminded of this dichotomy when reading SS-GB because, while its hero inhabits a grey, downbeat world, where dealing with even the simplest details of everyday life can be exhausting, some big, almost Bondian things hove into view and require his attention. These, though, hardly make his existence any more glamorous. Rather, they make it a lot harder for him than it was already.

In Deighton’s imagined alternative universe, SS-GB begins in November 1941. Nine months earlier, in February, Britain surrendered to Germany. February 1941 was four months before, in real history, Hitler turned against Stalin and ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union, an event that in in SS-GB evidently didn’t happen because the novel depicts Germany and the Soviet Union as, still, firm allies. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour, which drew the USA into the war against the Axis powers, occurred at the end of 1941 and hasn’t happened yet. One wonders if, here, it will happen, given the alterations elsewhere on the timeline. The USA remains neutral in SS-GB, whilst peering across the Atlantic at a fully Nazi-controlled Europe with wariness and trepidation. Incidentally, Deighton provides almost no exposition about what has gone on and it’s left to the reader to infer.

SS-GB’s hero, Detective Superintendent Douglas Archer, is a policeman at Scotland Yard who finds himself having to do his police-work under the supervision of the German occupiers. His immediate superior is General – ‘or, more accurately in SS parlance, Gruppenführer’ – Fritz Kellerman: “a genial-looking man in his late fifties… of medium height but his enthusiasm for food and drink provided a rubicund complexion and a slight plumpness…” Obviously, it was never put to the test, but Kellerman represents a good guess on Deighton’s part about how many German officials would have behaved if they had been posted to a defeated Britain and put in power there. They’d have behaved like amiable Anglophiles, dressing in tweed suits, going hunting and fishing on country estates, playing golf, guzzling Scotch whisky and stocking their rooms with British antiques. (Deighton has fun developing that last idea. He depicts a bunch of 1940s British spivs running an illicit trade in British heirlooms, aimed at the German occupiers.)

Archer fits neatly into those Germans’ image of Britain because he represents another cosy and much-loved British cliché: the famous sleuthing detective. Recognising him, one occupier exclaims, “You’re Archer of the Yard… You’re the detective who solved the Bethnal Green Poisonings and caught ‘the Rottingdean Ripper’ back before the war.” Later in the book, Archer plays up his fame among the Germans – at least, the ones who enjoy true-life crime stories – to his advantage.

Behind the bonhomie of the likes of Kellerman, however, lurks the despotic ruthlessness of Nazi Germany. Early on, Kellerman warns Archer about what may be coming. Of Scotland Yard, he says, “Neither of us want political advisors in this building, Superintendent. Inevitably, the outcome would be that your police force is used against British Resistance groups, uncaptured soldiers, political fugitives, Jews, gypsies and other undesirable elements.”

The story begins with Archer assigned to what looks like a straightforward murder case, a shooting in a rundown neighbourhood called Shepherd Market. The murder scene is a flat “crammed with whisky, coffee, tea and so on, and Luftwaffe petrol coupons lying around on the table. The victim is a well-dressed man, probably a black-marketeer.” Of course, Archer gradually realises there’s more to the case than initially meets the eye. And, as he grapples with the increasingly serious implications of what he’s investigating, he encounters a variety of characters who may be on his side or may be out to get him.

These include an officer in the SS’s intelligence service, an intense and driven man called Oskar Huth, who’s flown in from Berlin and put in charge of Archer and his investigation, and who’s the antithesis of the jocular Kellerman. When Archer meets him off his Lufthansa plane and inquires where his bags are, he snaps, “Shotguns, golf-clubs and fishing tackle, you mean? I’ve no time for that sort of nonsense.” Constituting the one glamorous element that enters Archer’s life during the book is Barbara Barqa, a foxy American journalist who’s been allowed into London by the press attaché of the German Embassy in Washington. She unexpectedly turns up at the murder scene and, predictably, isn’t all that she seems. Meanwhile, additional tension comes from Archer’s elderly sergeant, and mentor, Harry Woods. He’s a man ‘who fought and won in the filth of Flanders’ and ‘would never come to terms with defeat.’ It’s whispered that he has connections with the British Resistance movement, which makes Archer’s position very precarious.

As Archer’s investigation continues, I was, initially, a little disappointed by two of the main plot devices that Deighton uses. These devices seemed to me slightly obvious ones for an alternative-history / World War II novel set in early-1940s London. One is the race by various countries to develop a game-changing weapon – guess which weapon that is. Indeed, when Archer learns that the murder-victim was suffering from radiation poisoning, I was reminded of Troy Kennedy Martin’s masterly TV miniseries Edge of Darkness (1985), which had a policeman investigating a killing and finding himself embroiled in a huge conspiracy involving the nuclear industry. The other plot device is an operation to rescue an important personage whom the Germans have imprisoned in the Tower of London. If the rescue is successful, it’ll be a boost for Britain’s battered morale and a propaganda win for the British Resistance. Again, guess who that personage is.

To be fair, Deighton keeps both plot devices grounded. They’re wrapped in believably authentic realpolitik involving the neutral Americans, different elements in the British Resistance, and competing factions among the occupying Germans. And the way one of them is resolved, near the end, caused me genuine surprise. Also, there’s a subplot involving Karl Marx – whose remains are buried at London’s Highgate Cemetery – that I thought Deighton handled ingeniously.

But what really makes SS-GB a pleasure are Deighton’s descriptions of everyday life in occupied London – and what the ordinary population, war-weary, demoralised and living near the breadline, have to put up with. There’s ‘the green, sooty fog’ with its ‘ugly smell’, which doesn’t quite hide ‘advertisement hoardings, upon which appeals for volunteers to work in German factories, announcements about rationings and a freshly pasted German-Soviet Friendship Week poster shone rain-wet.’ There’s Archer’s landlady, whose soldier-husband is in ‘a POW camp near Bremen, with no promised date of release.’ She serves her policeman lodger eggs she got from a neighbour as payment for an ‘old grey sweater to unravel for the wool’, and a cube of margarine, ‘the printed wrapper of which declared it to be a token of friendship from German workers.’

And there’s a rather desperate-sounding gala evening at the Metropolitan Music Hall. This ends with the cast trying to cheer up the dejected London audience by ‘throwing paper streamers, wearing funny hats and popping balloons that descended from a great wire basket suspended from the ceiling’ – leaving the theatre ‘in a chaos of litter that had to be salvaged for re-use.’ The line-up for the evening includes Gracie Fields and Flanagan and Allen. No George Formby, though. Probably he’s in a prison camp, as a punishment for punching Hitler in his 1940 movie Let George Do It!

And there are the ruins and wreckage left both by the Blitz and by Deighton’s imagined German invasion. It’s a grey, wet, cold, blasted place, full of dejected and frustrated people, and it isn’t difficult to envision the London of George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) being a little further along the road. Deighton, who’s still with us at the venerable age of 96, was ten years old when World War II broke out, and he came from the Marylebone area of London. Presumably, he had images of the city in wartime seared into his memory and didn’t have to stretch his imagination too much to describe SS-GB’s version of it.

Thus, SS-GB’s crowning achievement is a depiction of Nazi-controlled London, and Britain, that you can practically see, hear, feel, smell and taste. Though of course, you really wouldn’t have wanted to.

© Harper Collins Publishers

Apparently, in 2017, the BBC turned SS-GB into a five-episode TV miniseries, starring Sam Riley, Rainer Bock, Lars Eidinger, Kate Bosworth and James Cosmo. I haven’t seen it, but let’s hope the BBC made a good job of it.