© Hammer Film Productions / Warner-Pathé Distributors

During the previous incarnation of this blog, before it had to be rebooted due to hacking issues, I published a series of posts under the title Cinematic heroes. This was about actors whom I admired, ranging from craggy action men like Rutger Hauer and James Cosmo to beloved old-school character actors like Terry-Thomas and James Robertson-Justice. Aware of a gender imbalance, I’d also intended to launch a parallel series of posts called Cinematic heroines, dedicated to my favourite actresses. But I never got around to it.

Anyhow, a week ago saw the death of the actress Barbara Shelley following a Covid-19 diagnosis. When I was a lad of 11 of 12 and a nascent film buff, Shelley was perhaps the first actress I developed a crush on. Thus, sadly and belatedly, here’s Cinematic heroines 1: Barbara Shelley.

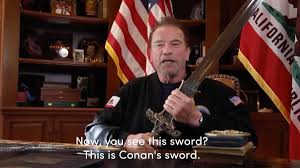

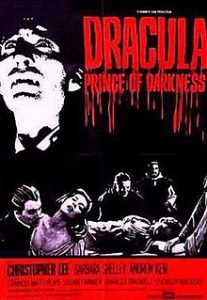

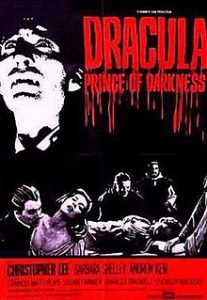

As well as being my first movie crush, Shelly starred in the first horror movie I saw that properly horrified me, 1966’s Dracula, Prince of Darkness. Before I watched it, and before I reached my second decade, I’d seen some quaint old black-and-white horror films made by Universal Studios in the 1940s, including a couple that featured John Carradine as Count Dracula. Carradine played Dracula as a gentlemanly, well-spoken figure who could change from bat-form into dandified human-form complete with a top hat. This hardly prepared me for Dracula, Prince of Darkness, made two decades later in colour by Hammer Films. It was a decidedly more visceral experience… Almost traumatically so for my young sensibilities.

Cloaked in an atmosphere of dread from the word ‘go’, it has four English travellers getting lost whilst holidaying in Transylvania and spending the night at the seemingly empty Castle Dracula. There, an acolyte of Dracula strings one of them up over a tomb containing the dead vampire’s ashes, slashes his throat and sends blood splashing noisily onto those ashes to bring the monster back to life. And monster he certainly is. Played by the great Christopher Lee, Dracula lurches around, hisses and spits, and glowers through red contact lenses like a literal bat out of hell.

Barbara Shelley is the second-billed actress in the movie, after Suzan Farmer, but she’s as memorable as Lee is. She plays Helen Kent, a stereotypically repressed and prudish Victorian housewife who, the traveller least enamoured with the apparent comforts of Castle Dracula, comes out with the prophetic line: “There’ll be no morning for us!” Later, bitten by the Count, she transforms from Victorian housewife into voluptuous sexpot, tries to seduce the surviving members of the group and bares her fangs animalistically at the sight of their naked throats. However, Helen’s sexual awakening is shockingly punished near the film’s end when another memorable actor, Lanarkshire-born Andrew Keir, playing a very Scottish Transylvanian monk, re-asserts the puritanical and patriarchal status quo. He and his fellow monks tie her down and bang a metal stake through her heart in a scene that evokes the cruelty of the Spanish Inquisition.

© Hammer Film Productions / Warner-Pathé Distributors

After all that, my eleven-year-old self was shaken – but also stirred, into a lifelong fascination with horror movies. And thanks to Barbara Shelley’s performance as a saucy vampire, I was probably stirred in more ways than one.

Born in London in 1932 as Barbara Kowin, Shelley took up modelling in the early 1950s and by 1953 had appeared in her first film, Mantrap, made by Hammer Films, the studio that’d later become her most important employer. However, she subsequently spent several years in Italy, making films there. It wasn’t until 1957 that she got a leading role in the genre that’d make her famous. This was the British-American cheapie Cat Girl, an ‘unofficial remake’ of Val Lewton’s supernatural masterpiece Cat People (1942). Cat Girl’s director was Alfred Shaughnessy, who’d later develop, write for and serve as script editor on the British television show Upstairs, Downstairs (1971-75), essential TV viewing during the 1970s and the Downtown Abbey (2010-15) of its day.

Slightly better remembered is 1958’s Blood of the Vampire, a cash-in by Tempean Films on the success that Hammer Films had recently enjoyed with gothic horror movies shot in colour. Indeed, Hammer’s main scribe Jimmy Sangster moonlighted from the company to write the script for this one. Shelley isn’t in Blood long enough to make much impact, although her character is allowed to be proactive. Hired as a servant, she infiltrates the household of the mysterious Dr Callistratus (played by legendary if hammy Shakespearean actor Sir Donald Wolfit), who runs the prison in which her lover (Vincent Ball) has been incarcerated. Callistratus, it transpires, is harvesting the prisoners’ blood to sustain and perhaps find a cure for his secret medical condition – for he’s actually a vampire. An uncomfortable blend of mad-doctor movie and vampire movie, Blood at least gets a certain, pulpy energy from its lurid storyline and Wolfit’s OTT performance.

The same year, Shelley got her first substantial role in a Hammer movie, although this was a war rather than a horror one, The Camp on Blood Island (1958). A half-dozen years later, she’d appear in its prequel, The Secret of Blood Island (1964), a film whose policy of casting British character actors like Patrick Wymark and Michael Ripper as Japanese prison-camp guards prompted the critic Kim Newman to write recently: “Even by the standards of yellowface casting – common at the time – these are offensive caricatures, but they’re also so absurd that they break up the prevailing grim tone of the whole thing.”

Before making her first Hammer horror film, Shelley appeared in 1960’s sci-fi horror classic Village of the Damned, based on John Wyndham’s 1957 novel The Midwich Cuckoos. She plays Anthea Zellaby, while the impeccable George Sanders plays her husband George. Like all the inhabitants of the village of Midwich, Anthea becomes unconscious when the district is stricken by some inexplicable cosmic phenomenon. And like every woman of childbearing age there, she discovers that she’s pregnant after she wakes up again. The result is a tribe of sinister little children with blonde hair, pale skins, plummy accents, super-high IQs, glowing eyes and telepathic powers who resemble a horde of mini-Boris Johnsons (well, without the IQ, eyes or powers).

These are cinema’s first truly creepy horror-movie kids. Child-actor Martin Stephens is particularly creepy as David Zellaby, Anthea’s son and the children’s leader. Still effective today, the original Village knocks spots off the remake that John Carpenter directed in 1995. It was also amusingly sent up as The Bloodening (“You’re thinking about hurting us… Now you’re thinking, how did they know what I was thinking…? Now you’re thinking, I hope that’s shepherd’s pie in my knickers….”) in a 1999 episode of The Simpsons.

© Hammer Film Productions / Columbia

After making a horror-thriller called Shadow of the Cat (1961) for Hammer, about the murder of a wealthy old lady (Catherine Lacey), a conspiracy by inheritance-hungry relatives and servants, and a supernaturally vengeful pet cat, Shelley got her meatiest role yet in the same studio’s 1963 horror film The Gorgon. This was directed by the man who’d make Dracula, Prince of Darkness, Terence Fisher, and also featured that film’s star, Christopher Lee. In addition, it featured Hammer’s other horror legend, Peter Cushing. Atypically, Lee plays the good guy here rather than the bad one, and Cushing plays the bad guy rather than the good one. The Gorgon is about a mid-European village terrorised by an unknown person who’s possessed by the spirit of Megaera, one of the three monstrous Gorgons from Greek mythology. (In fact, in proper Greek mythology, Megaera was one of the Furies.) Her victims are regularly found transformed into stone.

Since the Gorgon’s female, and since Shelley plays the only prominent female character, it’s hardly a spoiler to say that she turns out to be the possessed villager. Oddly, Shelley doesn’t get to play the character in Gorgon form. That honour goes to actress Prudence Hyman, sporting a headful of very unconvincing rubber snakes. While the monster is a big disappointment, and isn’t a patch on cinema’s scariest representation of a Gorgon, the Ray Harryhausen-animated Medusa in 1981’s Clash of the Titans, The Gorgon makes partial amends by having some wonderfully atmospheric moments.

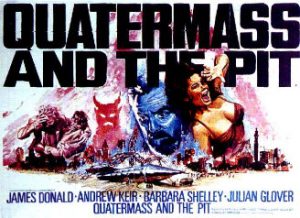

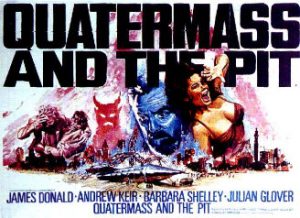

In 1966, besides appearing in Dracula, Prince of Darkness, Shelley appeared in Rasputin, the Mad Monk, which was shot back-to-back with the Dracula film and used many of the same sets and cast, including Christopher Lee as the titular character. Despite some good performances, I find this film a confused, half-baked affair. Happily, two years later, Shelley’s final movie for Hammer was also her best one. This was 1968’s sci-fi horror film Quatermass and the Pit, based on an original 1958 BBC TV serial of the same name. Both the film and serial were written by the same man, Nigel Kneale.

Pit has an ingenious premise. Workers on a London Underground extension project dig up some skeletons of prehistoric ape-men and what proves to be an alien spacecraft full of dead, horned insect-like creatures. The insects are identified by the film’s scientist hero Bernard Quatermass (Andrew Keir again) as inhabitants of the now-lifeless planet Mars. Five million years ago, they came to earth and staged an invasion by proxy. Unable to survive themselves in the earth’s atmosphere, the insect-Martians programmed the apes they encountered to become mental Martians. Since these apes were the ancestors of modern human beings, Quatermass memorably exclaims, “We are the Martians!”

© Hammer Film Productions / Seven Arts Productions

Unfortunately, it turns out that the Martians, in both insect and surrogate-ape form, conducted occasional culls whereby those with pure Martian genes / programming destroyed their fellows who’d developed mutations and lost their genetic / programmed purity. When the spacecraft is reactivated by a power surge from the cables of some TV news crews, it triggers a new cull. London becomes an apocalyptic hellscape where the human inhabitants who retain their Martian conditioning roam around, zombie-like, and use newly awoken telekinetic powers to kill those who no longer have that conditioning.

Shelley plays an anthropologist called Barbara Judd, a member of a team headed by Dr Roney (James Donald) studying the apes’ remains. They join forces with Andrew Keir’s Quatermass – sartorially striking in a beard, bowtie, tweed suit and trilby – who’s a rocket scientist come to examine the spacecraft. Shelley, Donald and Keir are endearing in their roles. It’s refreshing to see a film where the scientists aren’t cold-blooded, delusional, self-serving or plain weird. Instead, they’re decent human beings, working with an eager curiosity, a sense of duty and a very relatable sense of humour. Indeed, the film has a poignant climax, when the member of the trio who’s least affected by the influence emanating from the spacecraft makes the ultimate sacrifice in order to stop it.

Thereafter, Barbara Shelley made only a few more film appearances, most notably with a supporting role in Stephen Weeks’ Ghost Story (1974), a film with an unsettling atmosphere – perhaps because although it’s supposed to be set in the English countryside, it was actually filmed in India. It’s also interesting because it offered a rare screen credit for Vivian MacKerrell, the actor who was the real-life inspiration for the title character of Bruce Robinson’s Withnail and I (1987). However, she kept busy with appearances on stage, courtesy of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and on television. Fans of British TV science fiction of a certain vintage will know her for her appearances in the final season of Blake’s Seven (1981) and in Peter Davison-era Doctor Who (1983).

Barbara Shelley’s death on January 4th led to her being described in the media as a ‘scream queen’ and ‘Hammer horror starlet’, but both labels don’t do her justice. For one thing, her characters rarely screamed – the impressive scream she produced in Dracula, Prince of Darkness was actually dubbed in by her co-star Suzan Farmer. Also, the ‘Hammer starlet’ moniker implies she found fame due to her looks and physical attributes rather than her acting abilities. The moniker is frequently applied to actresses like Ingrid Pitt, Yutte Stensgaard, Madeline Smith and Kate O’Mara who worked with the studio in the 1970s, when relaxed censorship rules allowed more bare flesh to be shown onscreen. But working in a less permissive time, Shelley projected sexuality when she had to, as in the Dracula film, the same way she projected everything else – through sheer acting talent. It was a talent that fans of the classic era of British gothic filmmaking, like myself, have much to be thankful for.

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer